Diego Velázquez, ‘Las Hilanderas’, 1655-60, The Prado, Madrid.

Another ‘re-post’ today, as I am currently in Glasgow researching a trip which is coming up in September for Artemisia, details of which can be found in the diary (along with everything else, of course). It looks at a painting which concerns the maltreatment of a human by a deity, a theme that is perfectly summed up by Gloucester, in Shakespeare’s King Lear (Act 4, Scene 1): ‘As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods: They kill us for their sport’. It is one of the main themes of my talk on Tuesday, 11 July, 5.30-730pm – Heroes and Humans in which today’s painting will feature. The concluding Week 3 of the course Classical Mythology in European Art will follow on Wednesday 12 July. As well as telling some more great tales, we will think about what the pagan myths meant to the predominantly Christian audience who commissioned the paintings and sculptures we will be looking at. After a short summer holiday I will be back on Monday 7 August at 6pm for an Elemental August – starting with the sublime potter Lucie Rie, who manages to cover earth, air, fire and water. Gwen John, Paula Rego and Evelyn de Morgan will follow on the successive Mondays. I’ll have more news about that next week, so watch this space… or the diary.

My lock down project back in 2020 – writing about a Picture Of The Day every day for 100 days – should have ended with today’s painting, for reasons of symmetry. However, day 100 turned out to be a Saturday, and I had developed a tradition of talking about Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel on Saturdays… so this was the first painting I wrote about after my daily ritual had ended, at which point we were finally started to come out of lockdown. That context might explain some of what I said back then – but, then again, possibly not!

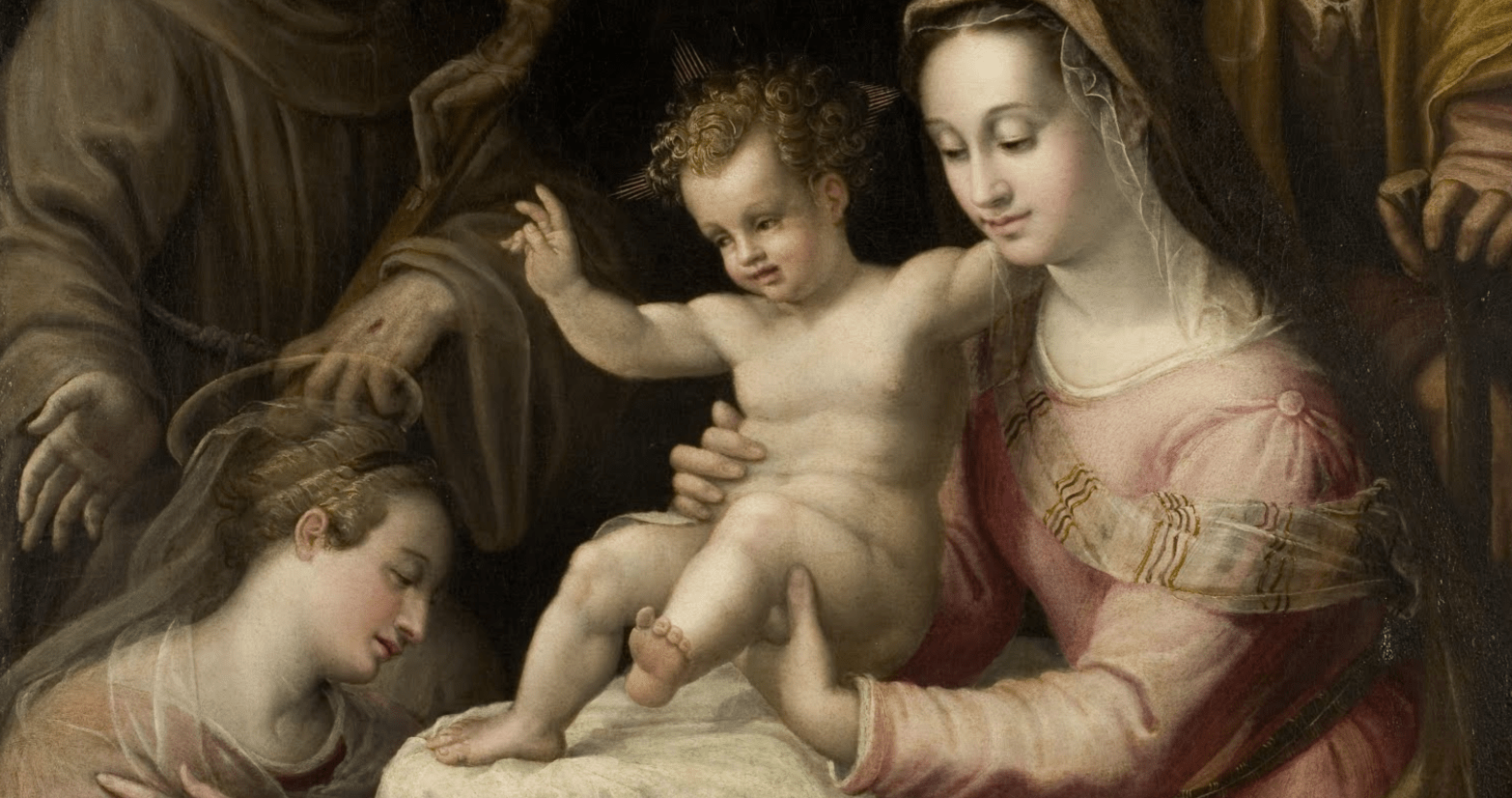

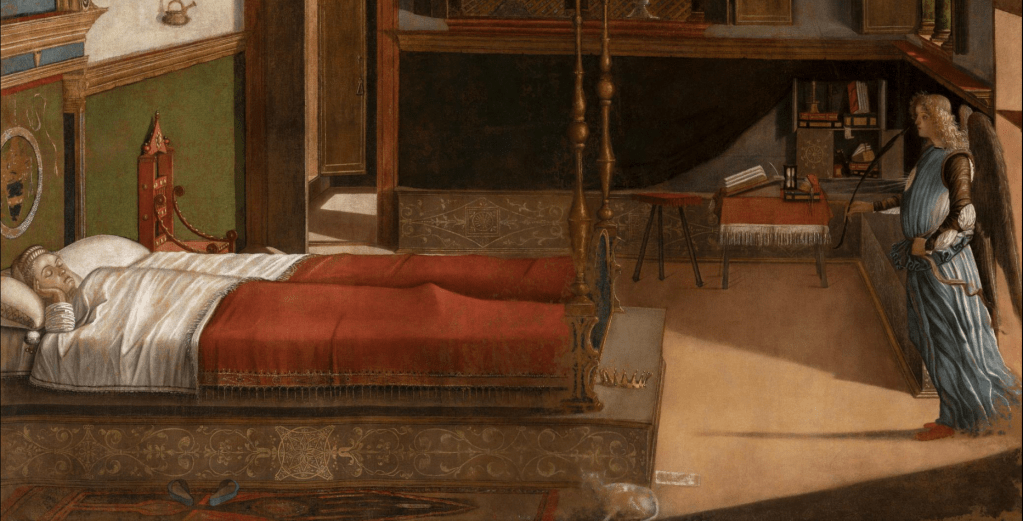

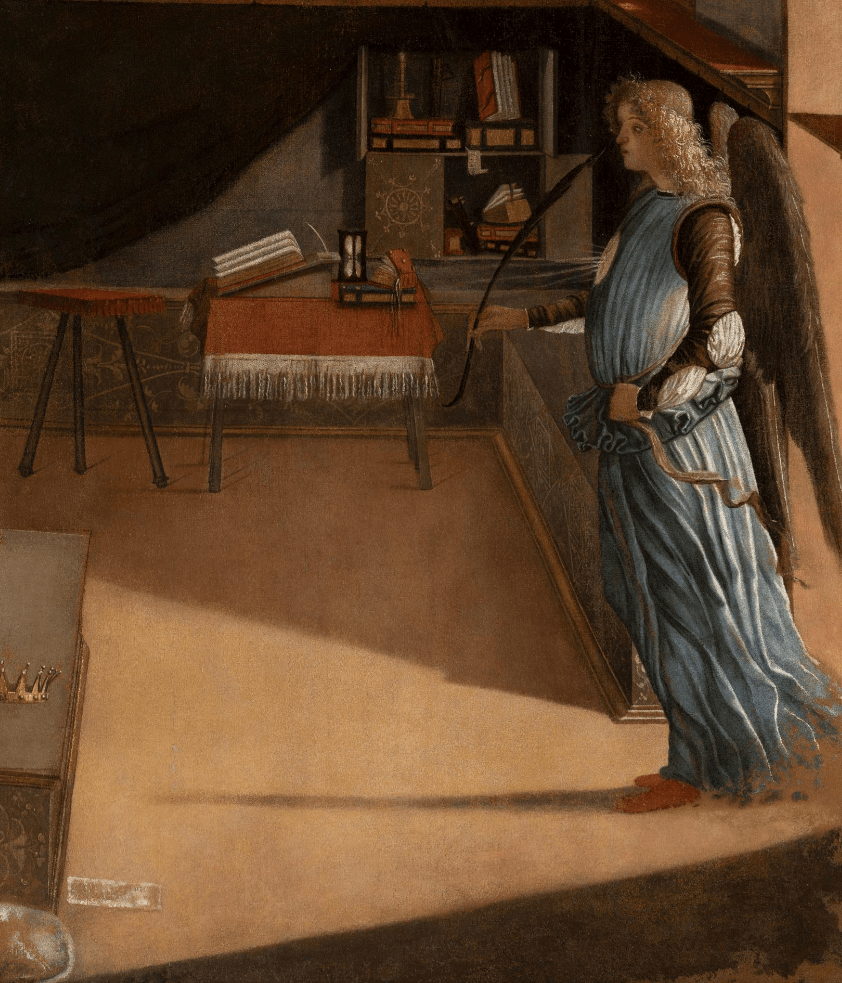

This painting is, I suspect, almost as complex in its ambitions and implications as the far more famous Las Meninas. Like it’s illustrious predecessor (this is probably one of the last paintings that Velázquez completed) it is very much about the nature and power of art. I’m using the Spanish title, simply because Las Hilanderas sounds so much better than ‘The Spinners’ – and also because it doesn’t put me in mind of a 1960s folk group. There is another title – The Fable of Arachne – but neither really explains what is going on, nor is either entirely accurate. There is, after all, only one person spinning: the old woman at the front left.

As it happens, Velázquez has illustrated three stages in the production of thread. The woman in the centre, wearing the red skirt, is reaching down to the ground for a ‘clump’ of wool. In her left hand is a carder – not unlike the working end of a broom, but with metal spikes. Carding wool is the process of separating the fibres, and lining them up. Once done, the carded wool would be handed to the woman on the left, who attaches it to the distaff, which is leaning against her left shoulder. She is pulling out separate fibres with her left hand, and feeding them onto a thread on the spinning wheel, spinning them together to create an even, strong yarn, which will then be wound onto a reel. The woman on the right is then winding the spun yarn from a reel, or skeiner, onto a ball. It’s not clear what the girl on the far right is doing – possibly taking the wound balls of wool elsewhere, or bringing the un-carded wool for the start of the process. The woman on the far left is pulling back a curtain. At first glance it is not clear why – but I shall come back to her later! There is also a cat, playing with one of the balls of wool, probably because that is one of the essential functions of a ball of wool – to be played with by a cat (I think that’s what’s called a circular argument). [Re-visiting this post, I wonder if the cat also represents the way in which the gods treat humans – ‘as flies to wanton boys’ – or, ‘as wool to playful cats’: a mouse would have driven the message home, but might not have been as picturesque].

Being brilliant, Velázquez manages to show us these stages in wool production while also creating a wonderfully balanced composition – with an old woman spinning on the left facing front, and a young woman winding on the right facing back. They are framed by younger women leaning in on either side, and in their turn, they frame the woman facing towards us, about to start carding the wool, in the centre. Even for Velázquez’ late style this central woman is remarkably freely painted, her face little more than a blur or blob. It’s intriguing to realise that one Spanish word for blob, blot, stain, or mark is borrón, whereas borra can be the sort of rough wool you would use as stuffing. As borrón can be used for the very painterly brushstrokes that Velázquez uses I would love to think – as several scholars have – that this is a deliberate pun.

Meanwhile, in the background, we have moved from raw material to finished product. The wool has been woven into tapestries, which hang on the walls of a brightly lit adjoining room, up a couple of steps almost as if it is a stage. The scalloped edges at the top confirm that these images are fabric, hanging from the walls, and tell us that they are held up in the corners of the room and half way across the walls. As many tapestries do, they have decorative borders and a pictorial centre. There are five people in this room, who in some way seem to echo the five women in the foreground.

The two who frame the group on the left and right look into and out of this subsidiary scene respectively, with the woman on the far right apparently aware of our presence: she looks out at us as we look in at her, past the women in the foreground. She is rather like Alberti’s ‘chorus’ figure who we have seen several times before (e.g. POTD 37), inviting us in, or warning us off. A woman in a blue dress and red shawl has her back to us, while the woman in the centre faces front. She is standing with her back to the tapestry, gesturing to a person wearing armour – a helmet and breastplate – and holding a shield. This is Minerva – Goddess of War and Wisdom – or Athena, if you prefer the Greek names. But as this is a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and he was Roman, I will stick with the Latin. In her role as Goddess of Wisdom, Minerva was also inspiratrix of the arts, and, as it happens, a dab hand at weaving. But then, so was Arachne – the woman gesturing towards her. In fact, Arachne was so good that she even boasted that she was probably better than Minerva – she certainly claimed all the credit for herself, and denied that she owed anything to the goddess. Minerva was clearly not going to be happy about this, and, disguising herself as an old woman, came down from Mount Olympus (where the gods lived) and challenged Arachne to a competition. They both wove tapestries. Minerva’s showed the twelve Olympian gods enthroned in their palace, with examples of the gods’ punishment of overreaching mortals as a warning to the presumptuous Arachne in the corners. Arachne, on the other hand, wove the loves of the gods – notably the many examples of Jupiter’s infidelities and dalliances with mortals. This angered Minerva, but she could not fault the craftsmanship, and while she appreciated Arachne’s work, she was also envious of her talent. She was, as people might say nowadays, conflicted. And this made her even more angry – she shredded the tapestry and attacked Arachne with her shuttle. The poor girl couldn’t cope with this, took a rope, tied it into a noose and tried to hang herself. But Minerva prevented her – she grabbed the rope, with Arachne hanging from it, and transformed her into a spider – an arachnid, of course – hanging from its thread, destined to spin forever.

It has been suggested that the two most important characters in the foreground – the old woman spinning and the young woman winding – are in fact Minerva and Arachne. However, I don’t think that this is necessarily the case – they could easily be contemporary workers whose activities are effectively ennobled by comparison with ancient myth. Nevertheless, the links between the foreground and background are clear, and Velázquez cleverly charts the development from fluffy lumps of wool (or was that blots, or blobs of paint?) through carding, spinning and winding, to the end product, a glorious, faultless work of art, both appreciated and abhorred by none other than Minerva. The process of moving from craft to concept, from technical skill to intellectual complexity, was one of the major developments in art during the Italian Renaissance. However, in Spain, artists had never really had the same respect. As with Las Meninas, Velázquez is making great claims for his art, the art of painting, in this particular work. From mere blobs of paint he can tell a tale – or, to put it another way, spin a yarn – which shows how dangerous art can be. It can rouse great emotions, it can teach us who we are and what we are capable of, it can stop us being complacent – which is why so many regimes have sought to bend it to their own will. I will leave you to contemplate our present government, and its current dealings with the arts.

But, of course, there is more to it than that. There’s a girl pulling back a curtain, for a start. I can’t see that the curtain has any real function in this space, so what is she doing it for? I’m sure it relates to the tale, told by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, about the competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, to determine who was the best painter. The rules were simple – each paints a painting, and then they decide which one is better. Once the works were completed, they went first to Zeuxis’ studio, where his painting was displayed behind a curtain. He had painted some grapes, and they were so good that when the curtain was drawn back birds flew down to peck at them – what could Parrhasius do that would be better than that? They headed off to Parrhasius’ studio, and he invited Zeuxis to go over and have a look. So Zeuxis went over to draw back the curtain, only to find out that it was a painting of a curtain. Zeuxis may have fooled the birds, but Parrhasius had fooled a person – and an artist at that. And Velázquez has done the same to us. Why is the girl pulling back the curtain? Well, she isn’t. There is no curtain. There is no girl, for that matter, it’s just a painting. But he’s so good that we end up talking about these things as if they are real. Did he know the story? Oh yes. All artists did by the 17th Century. I can’t help thinking that by pulling back the curtain, the girl is referring to the competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasius in order to reveal the story of another competition, the one between Minerva and Arachne – so are we to assume that Velázquez was also in competition with someone? Before I answer that question, let’s stick with the fabric. Surely there is also a comparison between the plain fabric of the curtain, and the elaborately pictorial fabric of the tapestries. And, if we wanted to take it even further, we could even stop and think about the fabric on which this is all painted – the canvas – once plain and flat, now richly decorated with unimaginable depths…

In another section of the Natural History Pliny praises a work by the artist Antiphilus called, ‘the Spinning-room, in which women are working with great speed at their duties.’ You could argue that Velázquez was trying to recreate this fabled image with Las Hilanderas – he is putting himself into competition with Antiphilus. Pliny was making the point that it takes great skill to recreate the sensation of movement in paint. He also refers to a painting of a four-horse chariot by Aristides, in which the horses were running. Inevitably, although Pliny doesn’t mention the fact, the wheels would have been spinning – and this is undoubtedly the effect that Velázquez is trying to achieve with the spinning wheel in his own work, the blurred, concentric lines creating the sensation of movement. By including the references to Pliny, and illustrating one of Ovid’s tales, Velázquez places his own work, in terms of craft and of concept, in relationship to the art of the ancients – but would he, like Arachne, be daring enough to challenge the gods? I’m just going to quote eight lines of the wonderful 18th Century translation of the Metamorphoses which I referred to when talking about Boucher’s Pygmalion (POTD 79) – and here is a link to a contemporary translation as well. We are a little way into Book VI, where Ovid describes Arachne’s tapestry:

Arachne drew the fam'd intrigues of Jove,

Chang'd to a bull to gratify his love;

How thro' the briny tide all foaming hoar,

Lovely Europa on his back he bore.

The sea seem'd waving, and the trembling maid

Shrunk up her tender feet, as if afraid;

And, looking back on the forsaken strand,

To her companions wafts her distant hand.

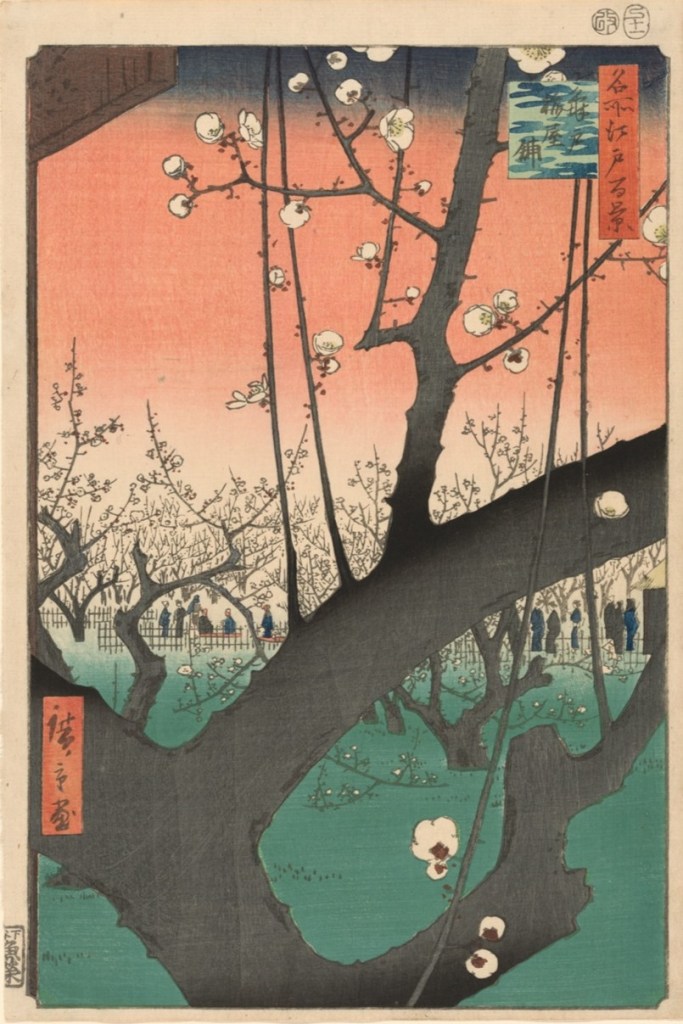

The first of Jupiter’s exploits woven by Arachne which Ovid mentions is the Rape of Europa, and if we look at the tapestry as painted by Velázquez, the version that Arachne has woven is the one painted by Titian for Philip II – which suggests that he was putting himself in competition with Titian as well. The Titian, now owned by the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum in Boston, and [at the time I first posted this] in the exhibition just about to re-open at the National Gallery, was copied by Rubens. Rubens’s version is displayed next to Las Hilanderas in the Prado, just to make the point. Rubens’s own painting of The Fable of Arachne – in which he too quoted Titian’s Rape of Europa – can be seen in the shadows on the back wall in Las Meninas – with the added justification that a copy of it, by Velázquez’ son-in-law Mazo, was actually in the room in which Las Meninas is set.

Not only can Velázquez chart the development from raw material to finished product, from unformed wool to refined tapestry – using blobs of paint to spin his yarn – but he can also acknowledge and recreate the works of the classical masters, while putting himself in the same tradition as Titian and Rubens – his own ‘gods’ of painting. Like Arachne, he challenges the gods, but unlike Arachne, he wins. From a purely personal point of view, I now relish the fact that the work that he quoted is a painting by Titian which I saw just a few days before lockdown. It was one of the last paintings that I saw – and it will be one of the first that I see when the National Gallery re-opens this week. It was, as you may recall, Picture Of The Day 1.