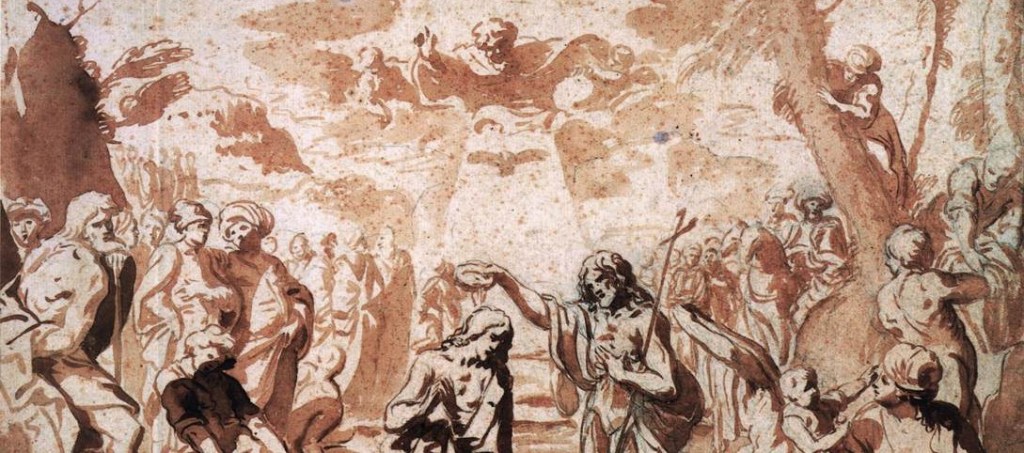

Elisabetta Sirani, Study for ‘The Baptism of Christ’, c. 1658. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Happy New Year! And Happy Christmas (yes, as I write, this is the Twelfth Day), and (given when I am writing) may I wish you a Happy Epiphany for tomorrow? The Wise Men will arrive and recognise Jesus as The Boy Born to be King. Thirty years later, Jesus will go to be baptised and John will recognise him as the Lamb of God: a second Epiphany. Back in the day both the Feast of the Epiphany and the Feast of the Baptism of Christ were celebrated on 6 January (so was the Feast of the Wedding at Cana, but that’s another story), hence my choice of image for today, a drawing of The Baptism by Elisabetta Sirani. Nowadays the Baptism is celebrated on the first Sunday after Epiphany, which this year is Sunday 8 January, coincidentally the anniversary of Sirani’s birth, which took place in Bologna on 8 January 1638. I first learnt about her two months into lockdown (see Day 62 – Portia), and she continues to fascinate me: her body of work is extensive, and yet she died at a mere 27, when so many artists today have not even started. She will, of course, feature in Women Artists, 79-1879 in Week 3, dedicated to the Baroque. I have now posted details of all of the talks, accessible via the diary, although tickets for Weeks 3-5 will go on sale after the talk on first talk, Women Artists 1: Following Fathers and Painting as Sisters, on Monday 9 January, 5.30-7.30pm.

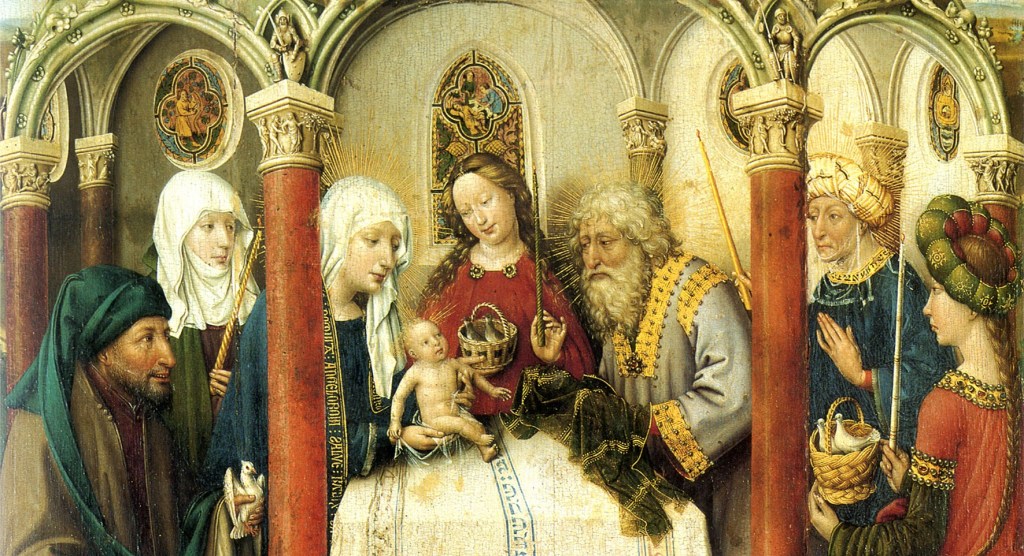

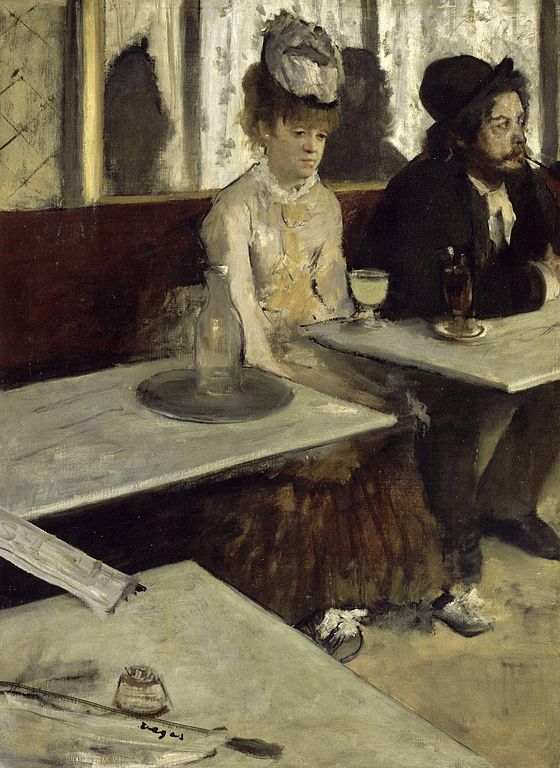

In many ways this drawing is entirely conventional – a product of its time. Essential to the story are the central figures of Jesus and his cousin, John the Baptist, engaged in the act of ritual purification by which he is defined. Not essential to an illustration of the story, but usually there for reasons which will become clear, are the figures of God the Father, looking down from above, and, in a broad beam of light, the Holy Spirit, descending in the form of a dove. Even less important – but common from an early period – are the onlookers, including those who have been, and those who are waiting to be, baptised, as well as the Pharisees and Sadducees grumbling in the background. What makes this particularly of its time is the number of onlookers – a far larger assembly than you might expect – and the way in which they are depicted stylistically (but more of that below).

If we start by focussing on the essentials, we can see that Jesus is kneeling on a rock, and apparently not in the water itself. Without checking every other baptism I’ve seen, I can’t think of any others like it. Also unlike many other depictions of the story he is wearing some form of drapery. In most images he wears only a loin cloth, and in some early paintings, even less, and is visibly naked. Sirani clothes him in something like a toga, but with no tunic underneath. This may well be due to the fact that it was considered unsuitable for a woman to depict (let alone look at) naked men – and a man in a loin cloth was, to all extents and purposes, naked. This drapery also strengthens Jesus’s relationship to John the Baptist, who is similarly attired – although the quality of his drapery is different. This could be in line with the biblical description of him wearing camel skin, or it may simply be that Sirani is giving Jesus a higher status. Notice how she draws attention to him by using a darker shade of ink for the shadows, a strength of contrast which is only equalled in the Baptist’s head: we are made aware of John’s presence, but it is Jesus who stands out. The figures in the background look further away not only because they are smaller, and because we can see the ground between them and us, but also because the ink is paler, and the details are not heightened with darker lines. It is a form of atmospheric perspective. As I hope this will show, Sirani’s drawing technique was extremely accomplished. You may be able to make out some faint, wispy lines – between the Baptist’s legs, and in the drapery across Jesus’s right thigh, for example – which give a clue to the development of this image. The materials quoted are ‘pencil, ink, and brown wash over black chalk on paper’. The initial sketch would have been in black chalk (what remains of this are the wispy lines), and this sketch which would then have been refined with pencil (although not in the form we have today, with graphite embedded in wood: the modern pencil was invented by Conté in 1795). The brown wash would have followed, and after this came further definition from the darker ink.

God the Father peers down from Heaven with his right hand raised in blessing. He is flanked by two angels, the one on our right supporting the robe which billows over God’s left arm. The Holy Spirit flies below them, looking suspiciously like an owl in this tiny sketch, but it’s only meant to be an indication. None of these characters have any definition from the darker ink, pushing them further away, and also making them more ethereal, as if seen in a vision. The beam of light, broadening as it descends, is not actually there at all, but represented by a gap in the clouds: we see it simply because it has not been painted whereas what surrounds it has.

The presence of these figures – God the Father and Holy Spirit at least – is what makes this episode so important. According to Luke 3:22 (and there are equivalents in the other synoptic gospels) immediately after the Baptism, ‘… the Holy Ghost descended in a bodily shape like a dove upon him, and a voice came from heaven, which said, Thou art my beloved Son; in thee I am well pleased.’ In one verse we have the doctrine of the Holy Trinity (not to mention an explanation of the Spirit’s appearance in art). Not only was Jesus the Boy Born to be King, and the Lamb of God, but also, the Son of God. Another revelation, another Epiphany.

I think the brilliance of Sirani’s draughtsmanship is made clear in this detail – admittedly most of the drawing – where we can see how she pushed the figures forward using the darker ink, without losing focus on Jesus. The gathered dramatis personae are framed, and so also contained, by the details of the landscape, a steep hill to the left, with mountains in the distance, and crossed trees on the right. These remind me of Titian’s sadly lost Martyrdom of St Peter Martyr, now known only through copies. The hills and trees, together with the heads of the onlookers, form the curved outer edge of an arc around the appearance of the first and third persons of the Trinity, and make an entirely coherent, if busy, composition.

There is a great description of Sirani’s drawing technique by a contemporary admirer, Carlo Cesare Pittrice:

‘I can truthfully say, having been present many times when some commission for a painting came, she quickly took the pencil and placing the pensiero [‘thought’, or in this context, ‘idea’] down quickly in two marks on white paper (this was the great master’s only method of drawing, which was practiced by few, not even by her father himself, if I don’t lie), dipped a small brush in ink wash; from this quickly appeared a spirited invention that seemed to be without drawn or shaded strokes, and heightened together all at once’

(quoted by Babette Bohn in ‘Elisabetta Sirani and Drawing Practices in Early Modern Bologna’, Master Drawings, Vol. 42, No. 3).

This ‘heightening’ Malvasia mentions is precisely the definition of forms using darker ink which I have discussed. As we can see from this detail, it is also used to created drama, through what we now see as a typically baroque chiaroscuro – the contrast of light and shade. The figure leaning against the rock on the left has details of both the drapery and anatomy heightened in this way, but he also casts a shadow onto the figure to the right, who is pulling on his hose (leggings), having just been baptised. The dark shadow initially makes this seated figure hard to read. The leaning figure is in quite a complex position, with one leg crossed over the other, the right hand behind his back, and the left resting on a stick in front of his chest. He also looks out towards us over his right shoulder – a position so convoluted in fact, that it seems that Sirani was clinging on to some mannerist tendencies from the 16th Century. Indeed, it has echoes of another figure, which I have up-ended to make my point.

And yes, I have now made reference to both Titian and Michelangelo in this one drawing. It is not impossible that Sirani was deliberately quoting these masters to demonstrate her knowledge of great art, and so her qualification for her job. Her fluency and skill cannot be doubted, and, given that there are few pentimenti (changes) that are clearly visible here, we could assume that she already knew what she was going to draw. It therefore seems likely that this is a modello, following on from other compositional studies (which no longer survive), a modello being a drawing presented to the patron for their approval. She received the commission – to paint The Baptism of Christ for the church of San Gerolamo della Certosa in Bologna – from Daniele Granchi, the prior of the monastery, in February 1657. The contract allowed two years until completion. However, the finished work is signed ELISABETTA SIRANI F MDCLVIII – 1658 (‘F’ stands for fecit which means, in this case, ‘she made’). She completed this painting in less than two years, and it measures, approximately, 4 x 5m. She was twenty years old.

Clearly there have been some changes compared to the presentation drawing. There are more angels, for example, both in the sky and on earth, including the two kneeling to our left of Jesus. One of them carries Jesus’s red robe, usually worn under the blue cloak, which, given the colour in the painting, we can see is the drapery Sirani has given him in the drawing. The other angel, to our left, carries a towel with which to dry the Son of God. How do I know it’s a towel? Well, it’s a guess, based on the fact that there are two more towels hung up to dry on the tree to the right. Notice how Jesus’s bright white towel grabs our attention, and falls from the angel’s arm thus leading our eyes straight to the signature. This is right at the bottom of the painting, and so closer (given how the painting is hung in its original location) to our eyeline. This was Sirani’s first important public commission in Bologna, and it made her name. She wanted us to know who she was – and her strategy worked. When she died seven years later, there was public lamentation.

The group on the right has also been extensively altered when compared to the drawing. The mother has lost one of her children, but gained a mother of her own, and the onlookers are altogether more animated. All of these alterations might have been made at the suggestion of the patron, having seen out drawing which was created for this purpose, but some might have been made by Sirani herself. They would clearly have needed further studies, and at least two have survived.

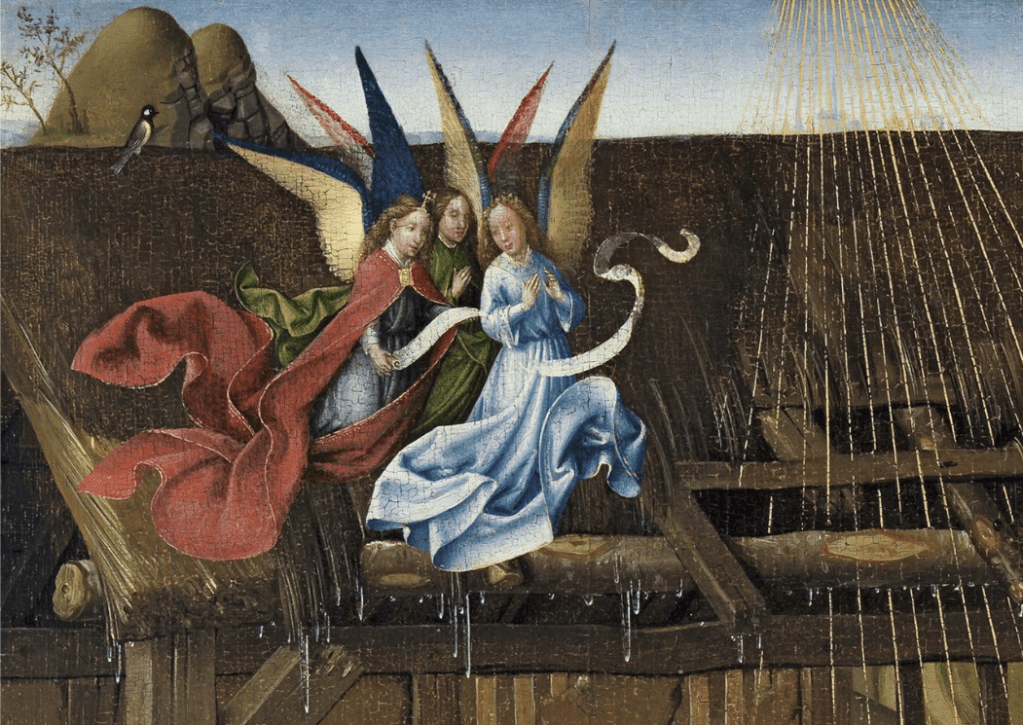

This elegant drawing for the group on the right is held in the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. It includes most, but not all, of the figures who would finally be painted, and uses a slightly different way of creating depth. The foreground figures are fully realised in terms of shading, whereas the semi-naked man further back only has a sketched outline. It is this definition without tone which distances him, as opposed to the tone without definition which we saw in the modello.

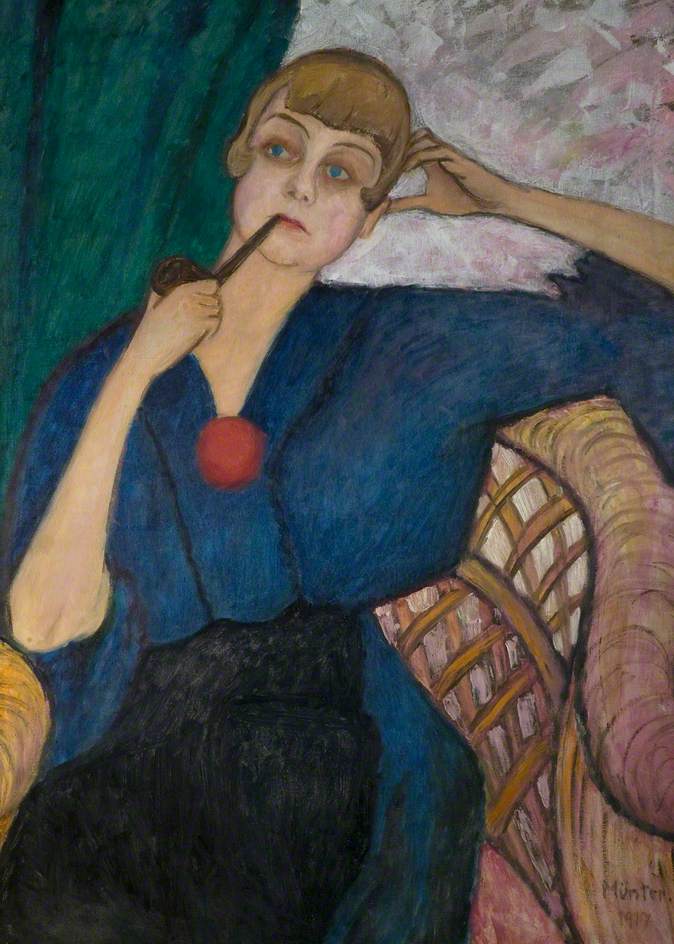

This highly finished red chalk drawing is for the man leaning at the front left. Rather than the Michelangelesque muscularity seen in the modello, he adopts a more relaxed pose in the finished work, and looks in, towards the action, rather than out towards us. It is one of at least 27 drawings by Sirani in the Royal Collection, which also boasts several more attributed to her less securely. She appears to have left about 200 drawings in total. We know a lot about her because she kept extensive records of everything she painted: about 200 works in a career spanning around a decade, of which about 120 survive. The three types of drawing I have illustrated show that she had a thorough grounding in academic techniques. She learnt these from her father Giovanni, who was himself a student of one of Bologna’s leading artists, Guido Reni. However, by the time Elisabetta was sixteen, Giovanni’s hands were so crippled with gout that he could no longer work – meaning that she had to support the whole family. She did this through her work, and also by teaching. As well as her two younger sisters, at least twelve other women appear to have studied with her. Given everything I have said, you may be wondering why so many people (not you, clearly) have never heard of her… Well, where do I start? I start on Monday, of course. Like so many women, Elisabetta learnt from her father, and the same is true of the women mentioned by Pliny in his Natural History nearly two millennia ago – hence the first part of the title of my first talk, Following Fathers and Painting as Sisters. We won’t get to Elisabetta until Week 3, of course, but there are plenty of other women who were masters of their art to consider before then.