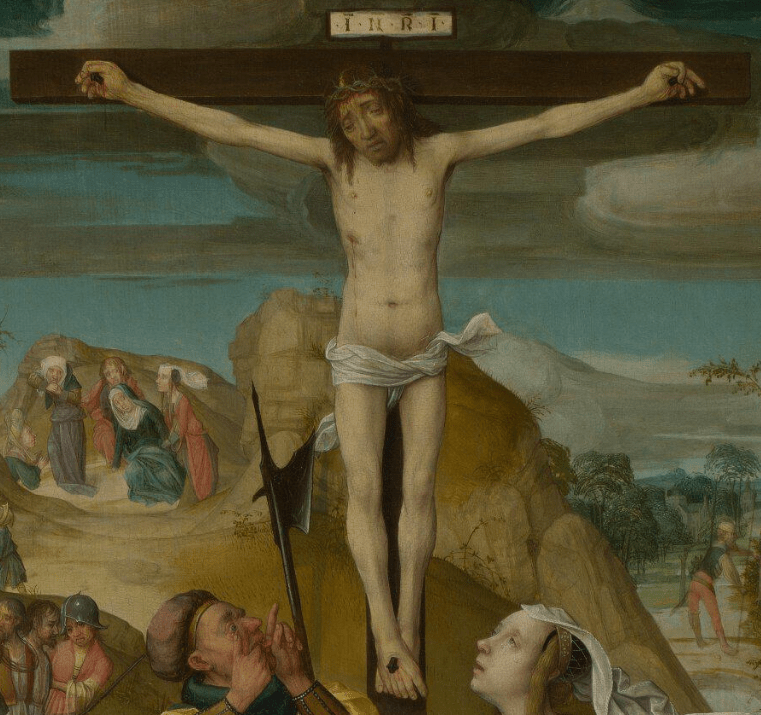

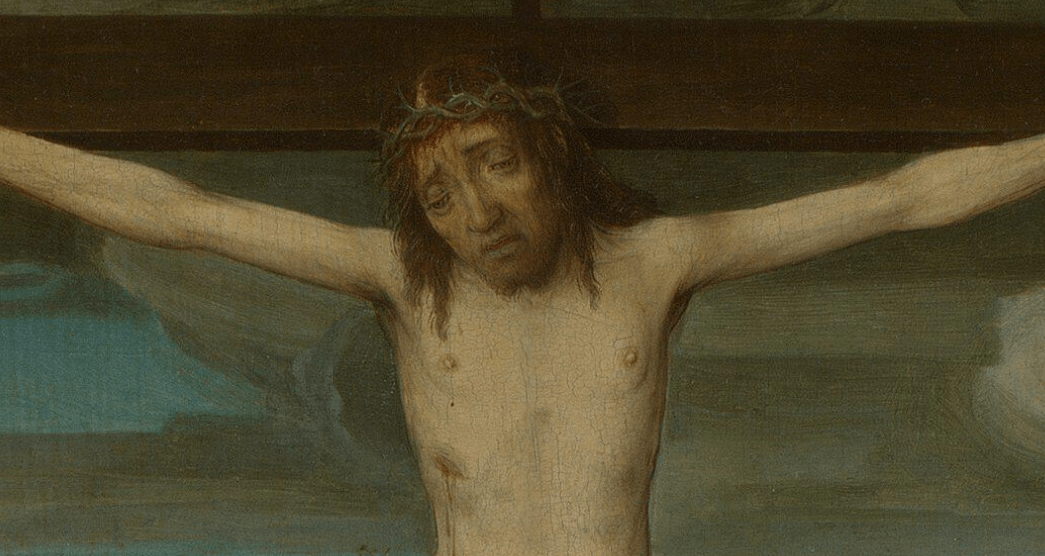

This is the same painting – although you would be forgiven for not recognising it. The work is a triptych – a painting on three panels – and for most of the time it would have been closed, only to be opened when mass was celebrated at the altar on which it was originally found. The ability to close altarpieces like this served several purposes, and one was purely practical: to keep dust off the richly coloured surface. The exterior panels were almost always far less colourful, and here, as so often, they are painted in grisaille – from gris, or ‘grey’, in French – a term for monochrome painting, which is usually intended to look like sculpture. As such, the exteriors of triptychs are not attention grabbing. When opened, the far richer colours would then draw people to the altar where mass was being celebrated, and conversely, when closed, the colour would be removed – ideal for a season so focussed on withdrawal and contemplation as Lent. This, of course, creates ambivalence. The richly coloured surface we have been contemplating throughout Lent should not have been visible. But by the time it could be opened – on Easter Sunday – then everything that has gone before is all but irrelevant, perhaps, as that is the day to celebrate the joy of the resurrection.

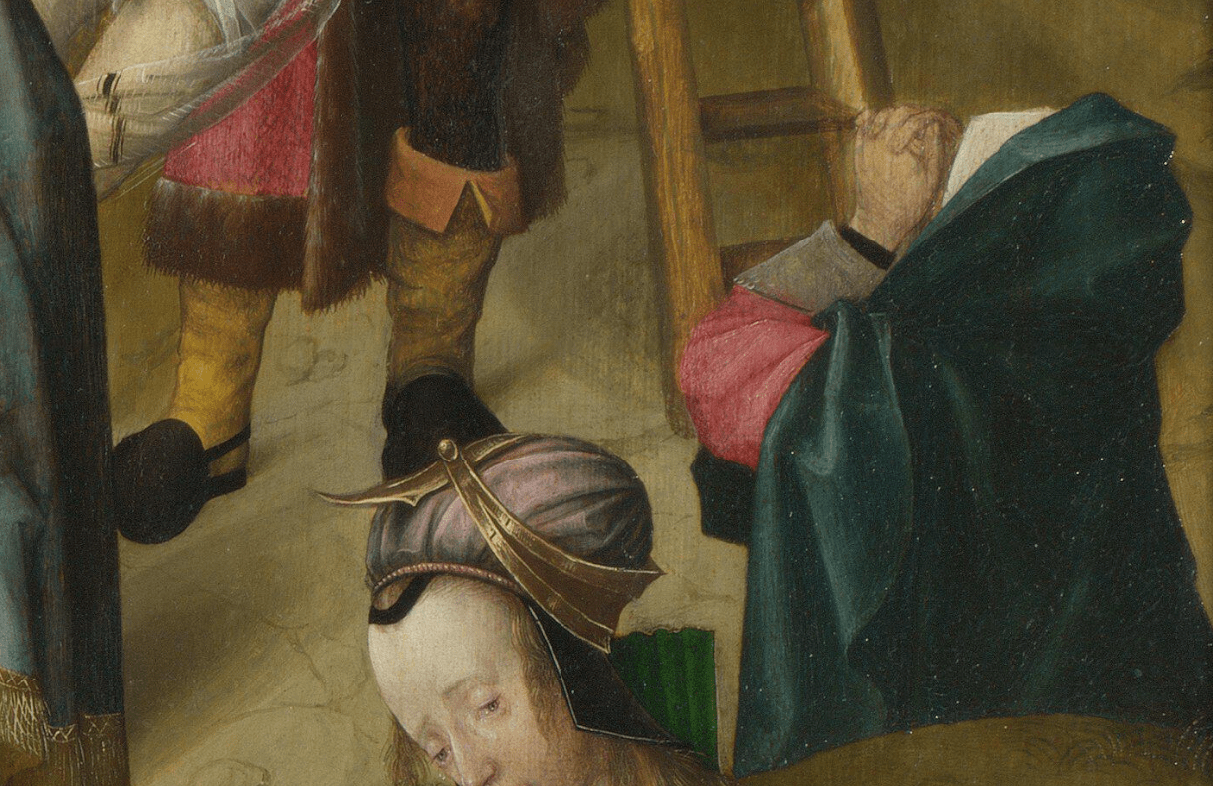

So what do we see here? There are four figures, conceived as stone sculptures, standing on irregular hexagonal plinths, casting shadows onto the backs of the niches in which they stand. The right side of each niche is more brightly lit than the left, which suggests that the main light in the chapel where this painting was originally located came from a window on the worshipper’s left. The ‘sculptures’ represent the Virgin and Child and St Augustine of Hippo on the left wing, and on the right are Sts Peter and Mary Magdalene. St Augustine can be identified because he is a bishop: he wears a mitre – the hat with two points – and carries a crozier, an episcopal equivalent of a shepherd’s crook, which indicates the care of his flock – all of the Christian souls in his diocese. He also wears a cope – the ceremonial cloak, or cape – which is fastened with an elaborate clasp, called a morse. But there have been many holy bishops. It is the heart that tells us this is St Augustine. It relates to a quotation from the the Book of Proverbs (23:26) in the Old Testament:

My son, give me thine heart, and let thine eyes observe my ways.

In a commentary on this text Augustine wrote,

“He says, give me. Give me what? Son, your heart. When it stays with you, it will go ill. You will be drawn to toys and to lascivious and harmful loves. Give me, he says, your heart. Let it be mine, and it will not perish.”

And this is precisely what Augustine is doing in this image – giving his heart to Jesus. Hence the presence of the Virgin and Child, as if any reason were needed. But why did the patron choose St Augustine to go on the outside of this painting? Quite simply because the Premonstratensians followed the Augustinian rule (see Lent 25).

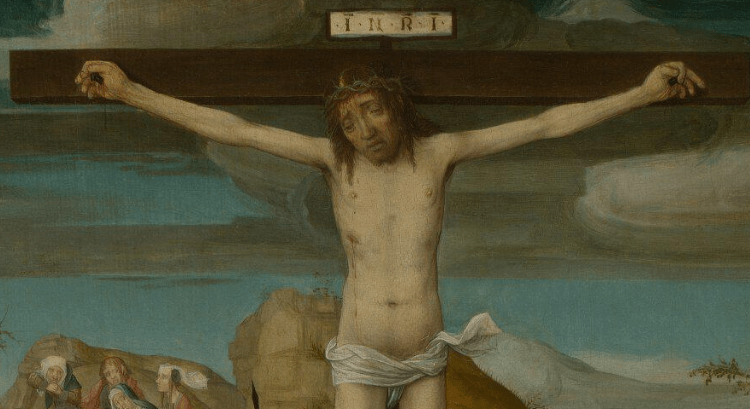

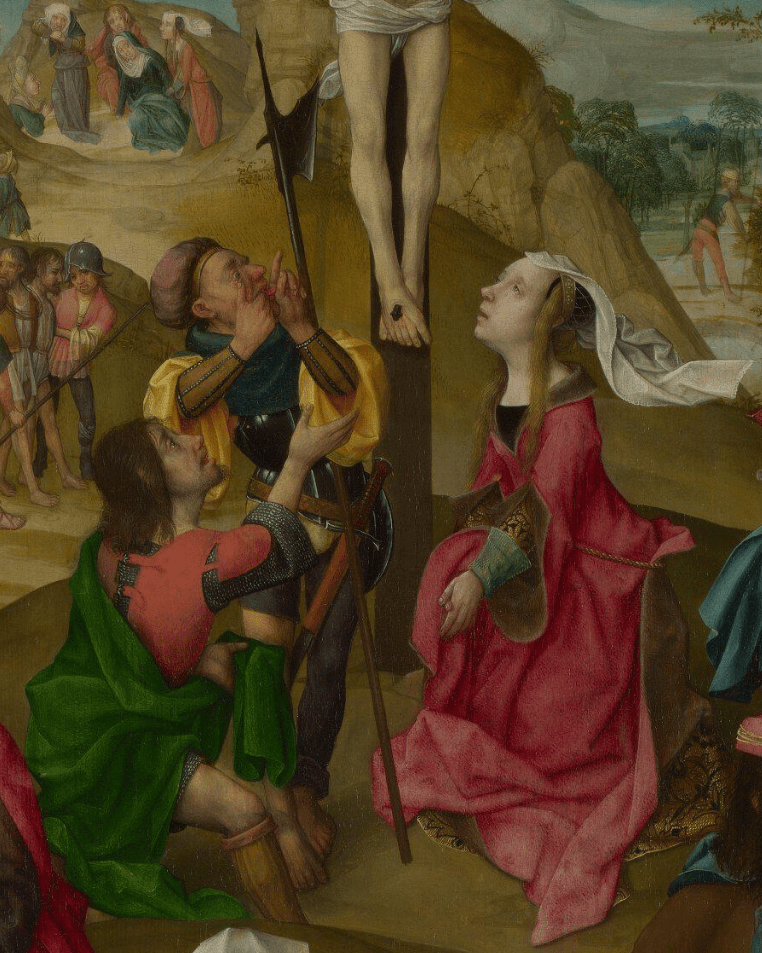

The presence of St Peter, identified by the key he is carrying, one of the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, is not so obvious, despite the fact that he was the first head of the Church after Christ. Nevertheless, his presence would remind the members of the convent that, after their allegiance to St Augustine, their ultimate responsibility (on Earth) was to the Pope. Also, given his status, Peter is hardly present on the inside of the altar, apart from a brief appearance, asleep, in the Garden of Gethsemane (Lent 10), so a dominant presence here is perhaps to be expected. The Magdalene, dressed differently compared to the interior scenes, but still holding her jar of precious ointment, clearly has a far more central role in the Easter story. She is, in some ways, the closest to Christ in the Master of Delft’s account. She is in the centre of the painting, at Jesus’s feet during the Crucifixion (Lent 32), and then again at the Deposition from the Cross (Lent 39). Given that many of the Canonesses would have been members of aristocratic families, being there against their will might, in some instances, have meant that their repentance from the ‘error of their ways’ would have been constantly required. Her strong female presence, opposite that of the Virgin Mary, would also have been relevant to all members of the convent, though. As for Mary, she too is central at the Crucifixion and the Deposition, serving to remind the Canonesses of their diverse losses, perhaps, and of the Christian endurance necessary to overcome them. Although ‘useful’ as a recipient of St Augustine’s heart, the Christ Child is also present simply to identify the Virgin: he is her chief attribute, or symbol. Indeed, many paintings called ‘Madonna and Child’ are, in truth, predominantly paintings of the Virgin, and Jesus is really there so that we know which female Saint we are looking at.

As for Lent itself – well, I hope you’re learning as much as I am! Cards on the table: I thought, ‘What painting is complex enough to cover the forty days of Lent,’ and this was the answer I came up with. So, on the first two days I planned all forty details. And then I gradually realised that it wasn’t going to stretch all the way to Easter, which, I must admit, was initially confusing. But why should it be ‘forty days’ in any case? Well, as a period of quiet and contemplation, it was made to commemorate Christ’s retirement to the wilderness for forty days. Admittedly, this was immediately after he had been baptised, so approximately three years before the crucifixion, but that is irrelevant. As a period of restraint – and of avoiding temptation – it is entirely appropriate. However, given that every Sunday is effectively a celebration of Christ’s resurrection, it was not deemed appropriate that these should form part of this period of sacrifice. So the Sundays between Ash Wednesday and Easter are theoretically not part of Lent… which is why Lent lasts 46 days rather than 40. And while we’re talking about it the name itself, ‘Lent,’ comes from an Old English word for the ‘Spring season’, which may itself derive from the idea that the days lengthen. And indeed they have – we have entered daylight saving – British Summer Time – and, as of today, we in England no longer have to stay at home. I, however, have planned a week which means I probably won’t leave the flat until Friday! I do hope that some of you are free to join me for some of this – starting with The Sistine Chapel, from ‘Beginning’ to ‘End’ today at 2pm and 6pm – BST! And tomorrow – back to the painting. Somehow.