Jacobello del Fiore, Justice enthroned between the Archangels Gabriel and Michael, 1421. Gallerie Accademia, Venice.

Great news! The Accademia in Venice, which houses today’s painting, is reopening on Monday 8 February, and the Vatican museums are already open – so things are looking up. Soon we will be able to get back and see things in the flesh, but for now, we will still be online. I’m really looking forward to my new, independent venture, which, like the Accademia, ‘opens’ on Monday: thank you so much to all of you who have already signed up. It is still possible to book for Monday’s talk, or for all three talks at the reduced rate, and will be until around noon on Monday, I suppose. Just click on Going for Gold for more details. Meanwhile, another glorious painting featuring a brilliant use of gold to get us in the mood.

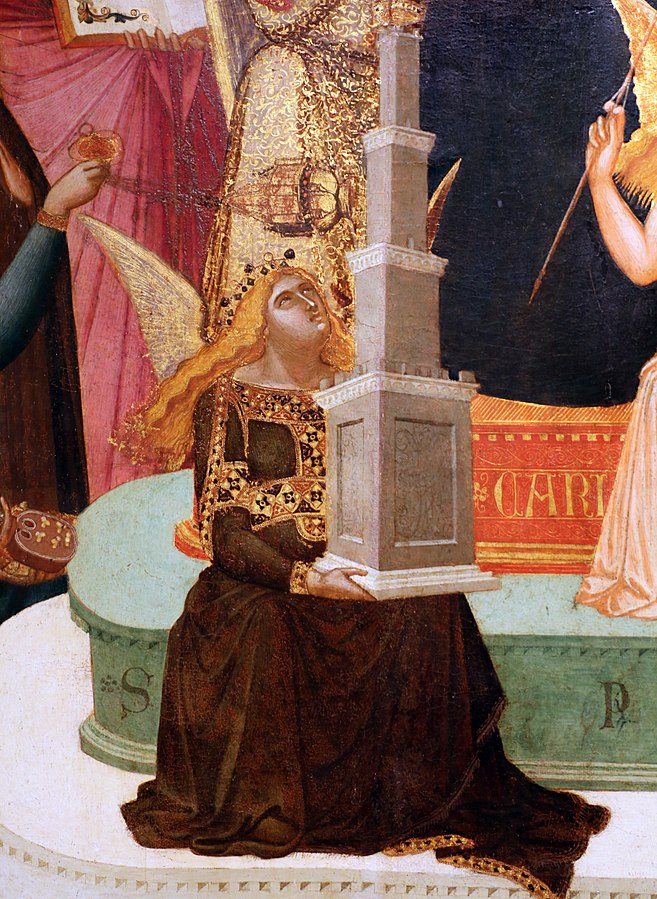

This has long been my first stopping point whenever I visit the Accademia in Venice, whether I’m taking a group or heading in on my own. It is at the top of the stairs as you enter, and all too easy to miss, because it is behind you on the wall as you sweep into the vast hall, which is a surviving element of the Scuola della Misericordia – the Confraternity of Mercy – which was converted into the city’s art gallery under the aegis of Napoleon. The painting itself comes from the Doge’s Palace, and was painted for the one of the judicial offices. It is both signed and dated to the left of Justice’s sword: ‘Jacobellus de Fiore pinxit 1421’– although, as you’ll see from the next image, when the painting was restored a few years back it turned out that this version of the signature had been repainted. The original name and date were still there, though, underneath the repainting. According to myth, Venice was founded on the Feast of the Annunciation (25 March) in the year 421, which implies that this painting was commissioned to celebrate the first millennium of the maritime republic’s existence. It is a triptych, of sorts, although not an altarpiece. The secular virtue of Justice, one of the four cardinal virtues (see Day 59 – Virtues vs Vices), and the one most valued by Venice, is flanked by two angels.

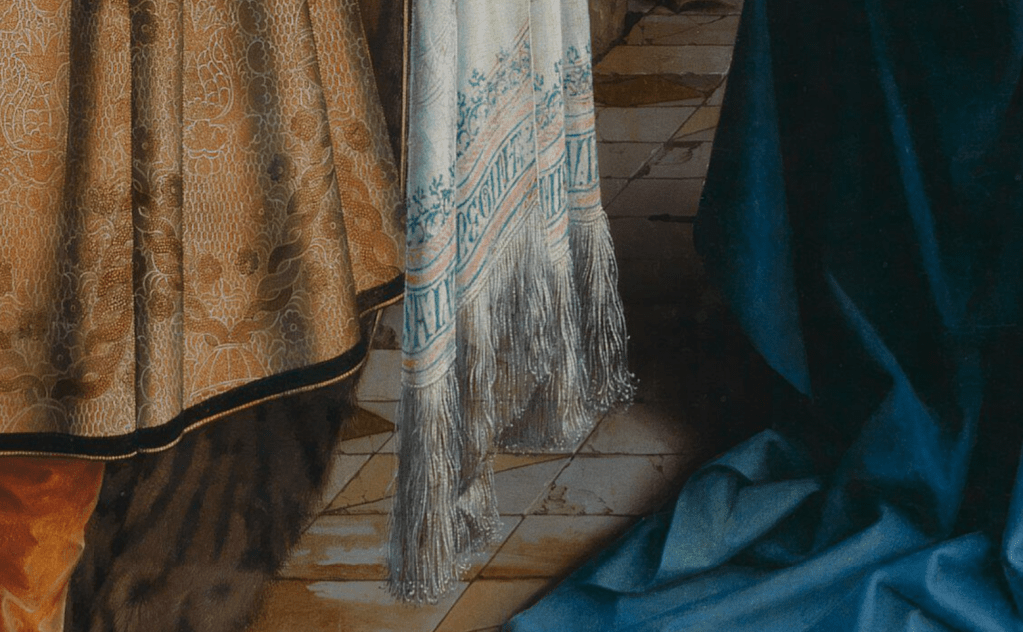

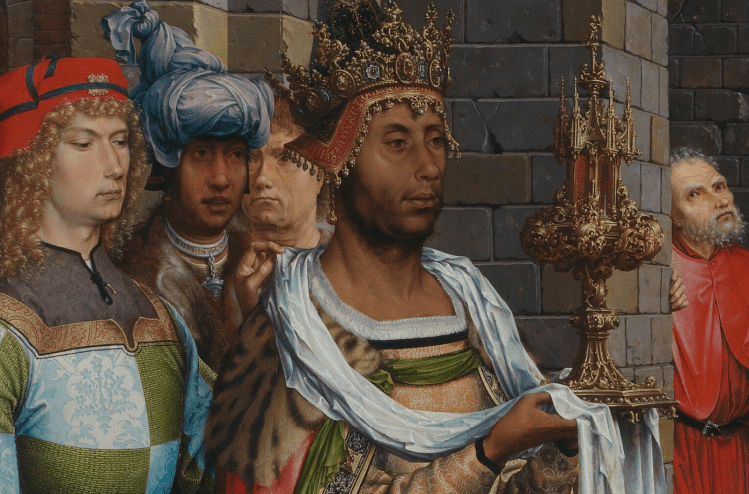

In this painting Jacobello shows himself to be one of the great exponents of the ‘International Style’ of painting, which swept, as its name suggest, across the whole of Europe in the last quarter of the 14th century and first quarter of the 15th. Elements of the style include a rich use of material – and we see that in the elaborate carving and colouring of the frame, not to mention the apparent encrustations of gold – and the depiction of rich materials – the wonderful red and blue fabrics, for example. Although it can include naturalistic details (the lions aren’t bad for the 15th century), overall the effect is more decorative, and there is often a fascination, as there is here, with hems forming elaborately scrolling lines, which pattern the surface rather than describe the naturalistic fall of the fabric. They are often called ‘calligraphic’ lines, as they are so much like some of the forms of decorative handwriting, or calligraphy. Even the scrolls show this format, although I won’t bother you with the translations (which means… I haven’t been able to track them down). Justice carries her standard attributes of scales and sword, and, although she is ‘enthroned’ no seat is visible. She may well be perched on the backs of the lions. Their presence is the first hint that all is not as it seems in this apparently straightforward painting. Lions are commonplace in Venice, you might say, but you are thinking of the winged lion of St Mark: these have no wings (but you’re not entirely wrong – the echo of St Mark’s beast can never be entirely forgotten in Venice). The lion is also one of the symbols often used by another cardinal virtue – Fortitude. This could also be relevant. But they are also indicative of the Throne of Solomon, known as the sedes sapientiae – the Throne of Wisdom – one of the titles given to the Virgin Mary. And if we remember that Venice was founded on the Feast of the Annunciation, maybe we should bear that in mind. Or am I getting ahead of myself? As we look at the painting, on the right is the archangel Gabriel, and on the left, Michael. Let’s have a look at him first.

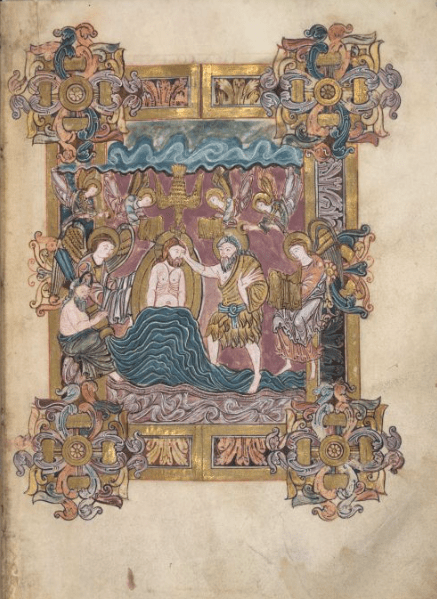

Michael is the divine representation of Justice. He is supposed to weigh the souls at the Last Judgement, and holds the same attributes as Lady Justice: the sword and the scales. He also holds a scroll in supplication to the virtue to ‘reward and punish according to merit and to commend the purged souls to the benign scales’ (that was the one I found). At his feet cowers a rather glorious dragon. We have a tendency to understand that, in the battle with the rebel angels, St Michael defeated Lucifer – which would be correct – however, the Book of Revelation (12:7-9) says,

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.

The text makes it clear that the dragon – or serpent – was the devil. Hence the dragon in this painting, and others, although elsewhere it can look a lot more human. It also explains the frequent confusion between Sts Michael and George, although it’s easy to tell the difference: Michael has wings, George doesn’t.

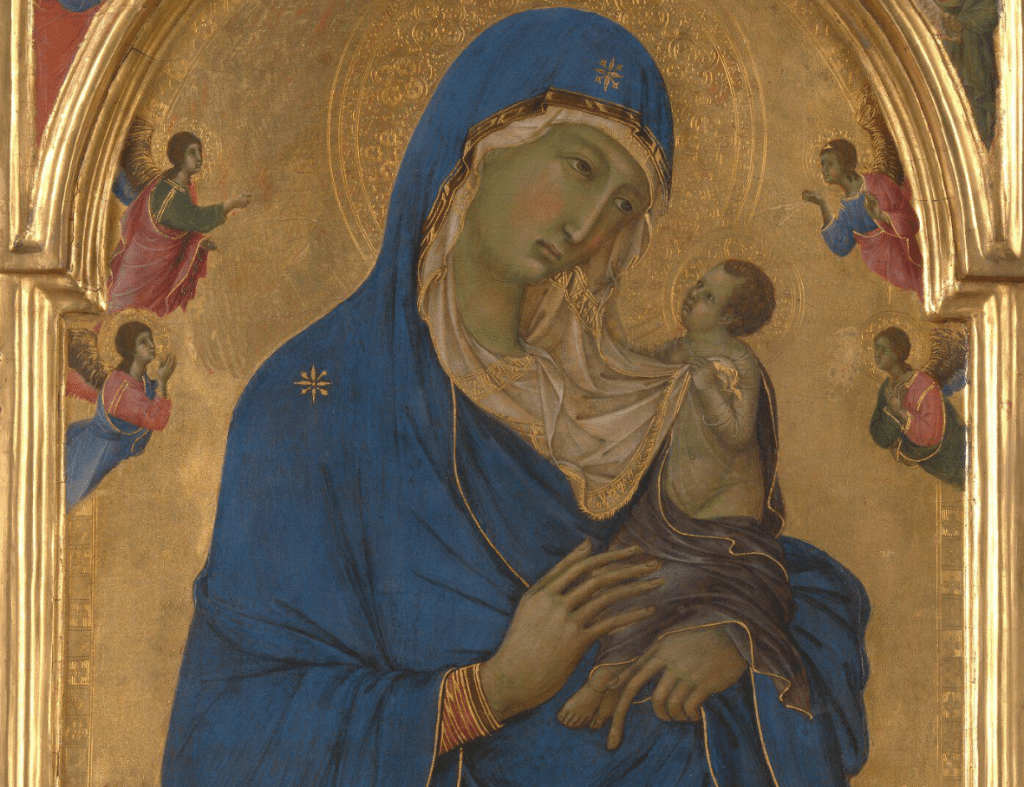

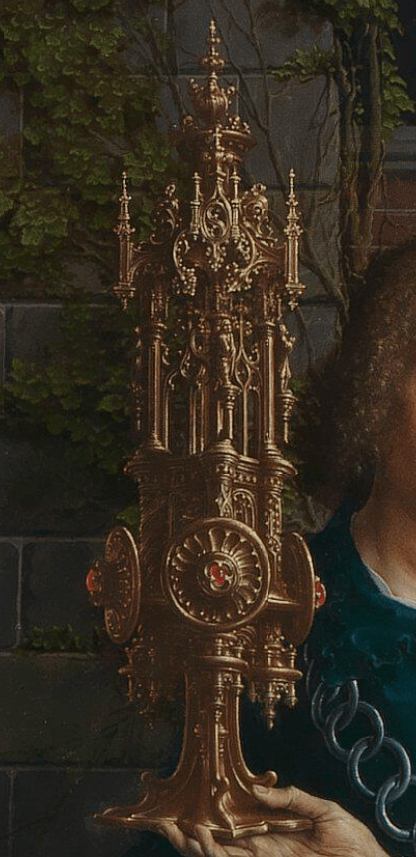

OK, so this isn’t the best photo, but it does give a far better sense of St Michael’s glorious armour. Like many other elements in the painting – the hilt of Justice’s sword, her breastplate, and the beam of her scales, for example – Jacobello is using a technique called pastiglio, the intention of which was to make it look like the objects were solid gold. Like the Duccio I was talking about earlier in the week (121 – A golden girl goes missing), this was painted on wooden panel, and prepared with gesso. Although the gesso is usually smoothed to a marble-like surface, it can also be modelled in three dimensions: it is effectively plaster, after all. This is what is done with pastiglio work. We think of paintings as being two dimensional, while sculptures occupy the full three dimensions. However, most paintings occupy depth as well, even if that is only because of the frame. For Jacobello, in this work, a lot of the surface of the painting, including all of St Michael’s armour, with the skirt and epaulettes, the front edges of his wings, and his halo, is in fact an elaborate relief sculpture.

Even given the brilliance of the gold, Jacobello manages to balance the bling with an original colour palette. Michael’s cloak, which wraps around his left wrist in full International Style splendour, is olive green, lined with a red lake. Somehow he manages to harmonize this with the graduation of the feathers on the wings, which move from cream, through mushroom and a greenish beige to salmon, vermillion and burgundy.

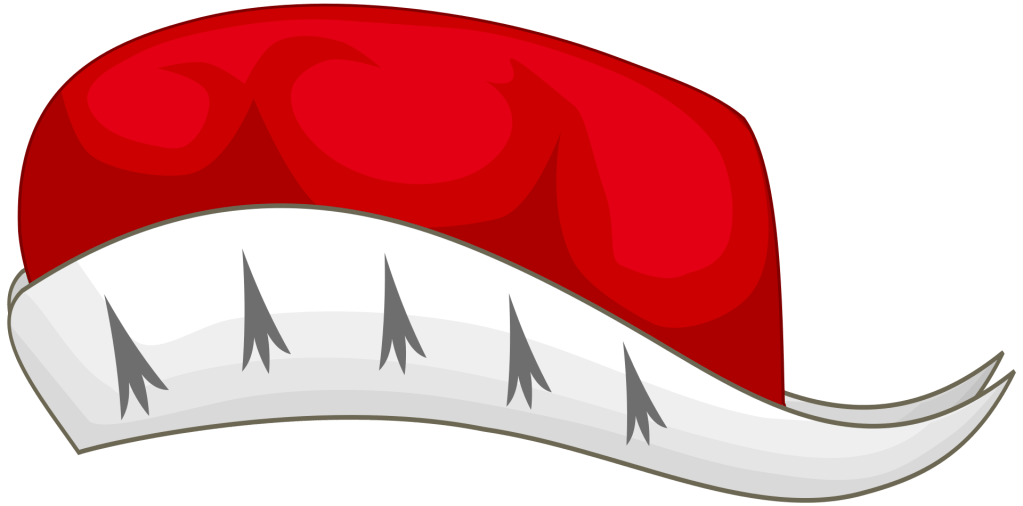

Rather gloriously, this is exactly the same palette as the dragon’s diaphanous, frayed, vegetal wings – or it would be, if only I could find better photos! The benighted creature flails helplessly with two of its clawed feet, hissing through its long snout, all too proud of its fine set of teeth. Like the gilded crest, they are built up in pastiglio – a rare example where the sculptural element is not gold, almost as if Jacobello had imbedded real teeth into the surface of the painting. And just in case we weren’t sure – and in case the dragon needed to know – the words ‘St Michael’ are painted just below the fluttering cape. So far, so good. Unless you’re a dragon.

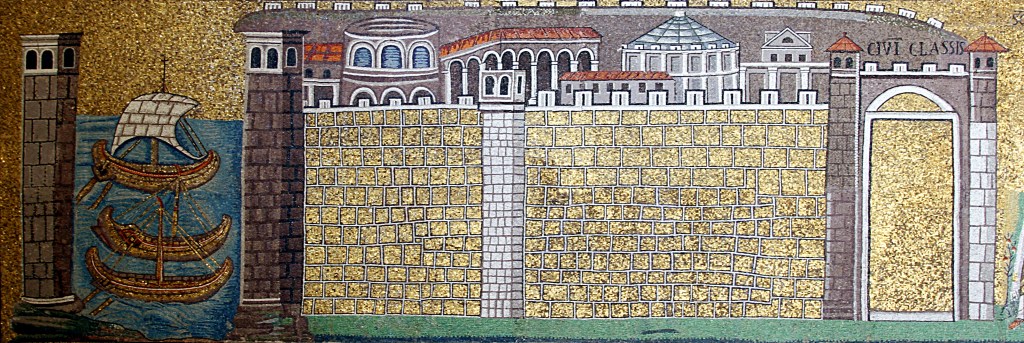

Now compare these two images. I have already mentioned that Justice was highly valued in Venice, and indeed, it was the most highly valued of the seven common contenders. So it is reassuring to see another, very similar representation attached to the Doge’s Palace. OK, so she doesn’t have the scales, but as she’s having to hold her own scroll, we shouldn’t hold that against her. The carving is attributed to Filippo Calendario, said to be the architect of the palace itself, and dated to the 1340s. There’s only one small problem. On either side of the figure’s head, you may be able to read the word ‘Venecia’. This is not Justice – this is a personification of Venice. Or rather, Venice is the personification of Justice. As for the scroll, the inscription translates as, ‘Strong and just, enthroned I put the furies of the sea beneath my feet’. If you want to be sure about ‘the furies of the sea,’ I should to show you the whole relief.

You can see the waves rolling underneath the throne – above the head of yet another lion – and left and right are two of the ‘furies’ – the anger of the sea and an enemy of the state – both of which have been trampled underfoot. The inscriptions behind her head and on the scroll tell us that this is ‘Venice’, and that she is ‘just’. Maybe, rather than simply calling our painting ‘Justice’, we should call it ‘Justice/Venice’? But, as she is ‘strong and just’, and given that lions are often an attribute of Fortitude, I suppose ‘Justice/Venice/Fortitude’ might be a better fit. Oh, and then there was that reference to the sedes sapientiae – although ‘Justice/Venice/Fortitude/Wisdom’ does seem to be pushing it. Maybe we should move rapidly on to Gabriel, with whom we are probably all more familiar.

This is truly one of the most luscious images of the archangel I know. He moves (unusually) from right to left, cloak and skirts fluttering in the breeze, the pale outside of the cloak – a faded pink, I suspect – echoing the tautological scrolling of the scroll, and contrasting strongly with the vermillion lining, to emphasize the calligraphic hemline. The scroll and cloak are also echoing the form of the wings above, curving up and then down to a point, while the wings themselves heighten the colours of Gabriel’s garb: the yellow is ‘lifted’ to gold, and the vermillion taken down to a burgundy similar to that seen on St Michael. And at the very top, the suggestion that these are peacock’s wings.

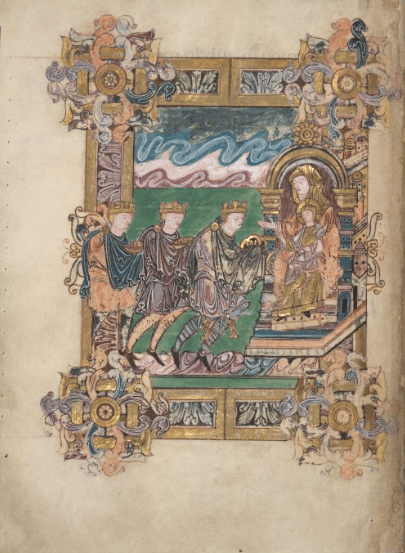

How do we know this is Gabriel? Well, he holds the lily, the sign of Mary’s purity, and speaks as he would to the Annunciate herself. Indeed, if we didn’t know that that he was announcing something to Justice, and if this was the only part of the painting to survive, we would assume this it came from a depiction of The Annunciation. If it were, his scroll would say ‘Ave grazia plena: Dominus tecum’ (Luke 1:28, in the Vulgate) – ‘Hail, though are art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee’, according to the King James Version. However, what it actually says is, ‘My word announces the virgin birth of peace among men’ (I got a bit obsessed and finally managed to track this down). It is a deliberate allusion to the Annunciation.

And remember, Justice is sitting on the sedes sapientiae, the Throne of Solomon, flanked by two lions, just as the Virgin Mary does in the National Gallery’s earliest painting, Margarito d’Arezzo’s Virgin and Child Enthroned, dating to the 1260s. Venice was founded, according to the myth I mentioned earlier, on the Feast of the Annunciation, in the year 421. One thousand years later, this painting recalls the event, eliding it with the Annunciation, and interprets the foundation of Venice as the foundation of peace among men. The Venetian myth continues: Venice was never invaded – it was inviolate – and so it was a virgin state. So I’m afraid it is not as simple as saying that this image represents ‘Justice/Venice/Fortitude/Wisdom’, as it also represents the Virgin Mary. Let this be a lesson to anyone asking about symbols. ‘What does that mean’ is one of the most frequently asked questions about objects in medieval and renaissance art, and rightly so. ‘Does it mean (a) or (b)?’ would be the next question. Well, sometimes it means (a) and (b) – although sometimes it means neither. The object just fits in, making the image more believable, and more real: it is purely observation to enhance the naturalism. However, in this case, it means (a) and (b) and (c) and (d) and (e). And some – we haven’t mentioned the ‘Peace’ of La Serenissima yet…

There is another way of thinking about it, though. We could see it as a representation of ‘Justice/Venice/Fortitude/Wisdom/Mary’, as all of these elements are included. Or, we could see it as the locals would have done: this is a representation of ‘Venice’. The qualities which are wrapped up into this one personification are all the things that Venice was supposed to be, and all of the qualities that are displayed in the buildings around the Piazzetta and the multiple functions of the Doge’s Palace: Justice/Venice/Fortitude/Wisdom/Mary could be seen as equivalent to Courts/Council Chambers/Prison/Library/St Mark’s. As it happens, I’ve said this before, but in a different way, illustrating the ideas with a painting by Canaletto: head to Day 65 – Venice if you want to see how that works. And if it’s all too much to cope with, just enjoy the rich colours, the elaborate folds, and above all, the gold – look at the sun on Justice’s breastplate, shedding light onto the world, for example. That’s one of the attributes of ‘Truth’, by the way…

The Venetian Republic was truly remarkable, and clearly thought very highly of itself. Of course, Venice is still remarkable, and let us hope it longs continues to be so. I’m really looking forward to Jane da Mosto’s lecture for my friends at Art History Abroad this Wednesday, Caring for Venice – sadly I can’t watch it live, but they (unlike me) record their talks, so I’ll watch it later. If you’re interested in what is happening to save this, the most remarkable of cities, it would be an ideal opportunity to do so. Not only that, but a percentage of the ticket price will be heading towards the charity with which Jane (wife of Francesco da Mosto, Venetian architect and T.V. presenter) is involved: ‘We are here Venice’ (I think the name loses something in translation). But before then we launch Going for Gold: I hope to see you on Monday!