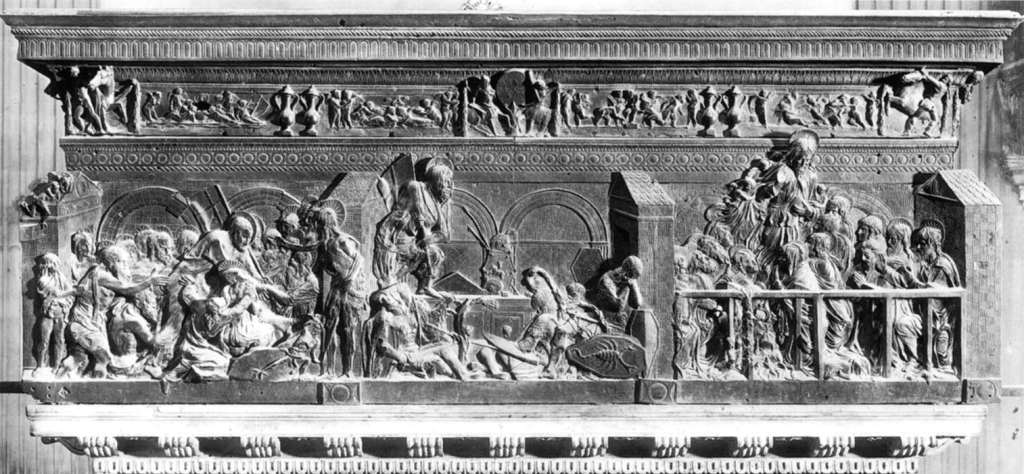

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Supper at Emmaus, 1601, National Gallery, London.

People often ask me what would be the best book to read as an introduction to renaissance art, and my answer is almost invariably ‘the Bible’. And its value is not restricted to the Renaissance. Most ‘Old Master’ painting was produced in a profoundly Christian world, and that outlook informs it all, in some way – although the relevance is hard to find in most paintings with classical subject matter. Nevertheless, it would be useful for this painting. Isn’t it odd how you don’t always know how things fit in? I’ve always known that ‘The Supper at Emmaus’ must happen after Easter – it has to happen after the Resurrection – but I hadn’t stopped to check exactly how long after the Resurrection it was. It turns out that it happened on Easter Sunday. According to Luke 24:13, ‘two of them went that same day to a village called Emmaus’. So I could have talked about this last Sunday – but I had another Resurrection in mind (Picture Of The Day 25).

The two met Jesus on the road to Emmaus, but didn’t recognise him. On arrival they invited him to dine with them, and only when he broke bread did they click – at which point he disappeared. Their response is one of amazement. The man on the left – a repoussoir figure, pushing our eye into the depth of the painting (see POTD 27) – thrusts his head forward, and puts his hands on the arms of his chair to push himself up to get a better view. On the right the man throws out his arms in amazement – although this gesture has other implications. He could almost be saying ‘but I thought you’d been crucified’, demonstrating by acting out Christ’s position on the cross. The arms stretched wide also say ‘the room is this deep’. Caravaggio uses the foreshortened arms to give depth to the painting, and to lead our eyes from the foreground back to Jesus. In between the two astonished onlookers, it seems quite clear to me that the innkeeper, or waiter, standing at the back of the table having delivered the food, doesn’t have a clue what is going on, or why this man is waving his hands over the table.

So why didn’t they recognise him? I think a conversation I had with one of the school groups I took around the National Gallery is worth thinking about. If you want to get people of any age to look at paintings you should always start by asking them what they can see – then you can tell how much they already know, what their frames of reference are, and what interests them – and you can then develop those lines of thought, nudging them gradually in the right direction. It was a group of teenage boys. For anyone, the question ‘Who is the most important person in the painting?’ will always get you somewhere. In this case the answer that came back was, ‘The woman in the middle’. Always try to go with the flow. ‘And what’s going on?’ I asked. The reply: ‘They’re having an argument’. ‘Why?’ ‘She cooked a bad dinner’. I must confess, at this point I did have to disagree with them – the chicken in particular looks as if it has an especially crisp skin, and I can imagine it being tender underneath. Having got to this stage, I thought it would be worthwhile pointing out that the person in the middle of the painting was actually Jesus, at which point they all, spontaneously, adopted positions like the people in the painting. They were astonished, and acted accordingly, just like these men. Apart from one lad at the back who hadn’t been paying attention up until this point and had no idea what his mates were surprised about. He ended up looking like the innkeeper…

So why didn’t they know it was Jesus? Apart from a cultural distancing from Christianity, that is. The disciples should have known, surely? Well, it doesn’t look like Jesus. Does he look like a woman? Not to me, but I can see what they mean. He doesn’t have a beard. Everyone knows Jesus had a beard. It’s in all the pictures. Well, not all of them. In the earliest images of Jesus as the Good Shepherd he is clean-shaven, but by the 10th Century he was almost always bearded. There is one notable exception, but more about that later on.

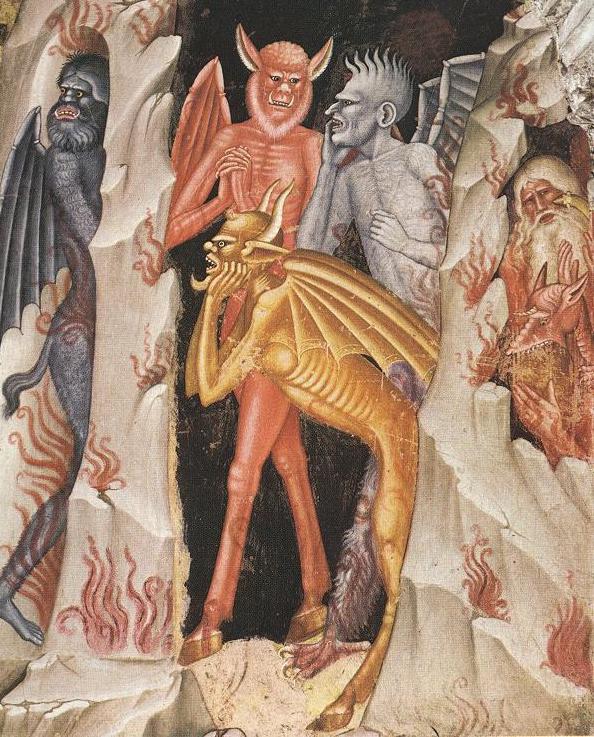

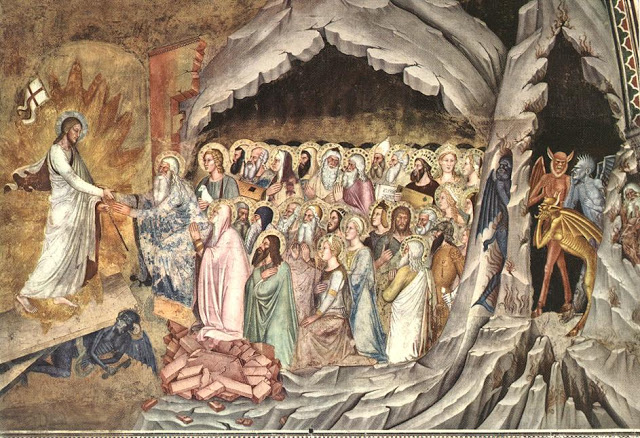

The other thing is, he’s not wearing his usual clothes. He usually wears a red robe with a blue cloak over the top – but here he’s wearing a white cloak. Why has he changed? Well, this is how he looks after the Resurrection. Here’s a detail from a painting by Jacopo di Cione in the National Gallery.

The shroud has been repurposed as a toga (see POTD 24), and that’s exactly why Caravaggio dresses him in white. This has the added advantage that the white of the shroud represents Christ’s purity. And the red? Well, his blood, his passion, his suffering… These are after all the colours of the flag he is carrying in this detail – the Cross of Christ Triumphant, the red of the passion on the white of his purity. It was adopted by the crusaders fighting in the holy land, who adopted St George, a soldier fighting for God as their patron. It is his flag too… and he became the Patron Saint of England some time in the 1340s. But more about him next week!

So, at some point in between the Crucifixion and his appearance on the Road to Emmaus Jesus has found time to shave and change his outfit. It’s hardly surprising they didn’t recognise him. But there are another couple of reasons, I suspect. Look at the way he is blessing the food. His right hand is raised, and the backs of the fingers and the thumb are just catching the glancing light, arriving as it so often does in Caravaggio from the top left of the painting. The left hand is cast in shadow. This brings me back to the other significant artist who painted Jesus without a beard. They both had the same name. No, not Caravaggio. Today’s artist was born in Milan, but brought up in Caravaggio, which is why he is ‘da Caravaggio’. On this basis I would be ‘Richard da Lewisham’ which somehow doesn’t quite have the same ring about it. His given name was actually Michelangelo, but we tend not to use that as it might get a bit confusing. However, the young Caravaggio (and dying at 39 he never got that old) must have grown up fully aware of the genius of his eponymous forebear, and probably wanted to emulate him if not surpass him. So look at this detail of Christ from the older master’s Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

Yes, he is beardless. And look at the position of the hands. Usually in a Last Judgement Christ raises the souls on his right hand to Heaven, and damns those on his left hand. Michelangelo’s Christ seems merciless, and is only concerned with a forceful gesture of damnation for all, an unequivocal ‘Go to hell!’ The curmudgeonly master was known for his ‘terribilità’ – his ability to provoke awe or terror. The gesture is almost the same in Caravaggio’s painting, only relaxed. The right, blessing hand is now lower, at shoulder level, and catches the light. The left hand, used for damnation, is in shadow – no coincidence.

Jesus also has a shadow behind his head. This could almost be another reason why he had not been recognised – there is no ethereal glow around this Saviour, it’s more like an anti-halo. I suspect that it might have something to do with the fact that he is just about to disappear. However, it is actually cast by the innkeeper’s head. Below and to the left you can see the shadow of his shoulder and arm – which then touches the arm itself at the elbow. This can only mean that the innkeeper’s elbow is resting on the wall. Look where arm and shadow meet: coming down in opposite diagonals, they touch and form a downward pointing arrow, pointing at Christ’s blessing hand – a very clever piece of direction from Caravaggio. Because the light is coming from the top left, the innkeeper’s face is in shadow – this could be symbolic of his confusion. To use the contemporary evangelical phrase, he hasn’t seen the light. Jesus seems to have leant forward to bless the bread, and before this, sitting upright, he would have been further back, in the innkeeper’s shadow. So what is happening here? He leans forward to bless the food, moves into the light, the two travellers see his face clearly for the first time – and they recognise him. And at this point, he