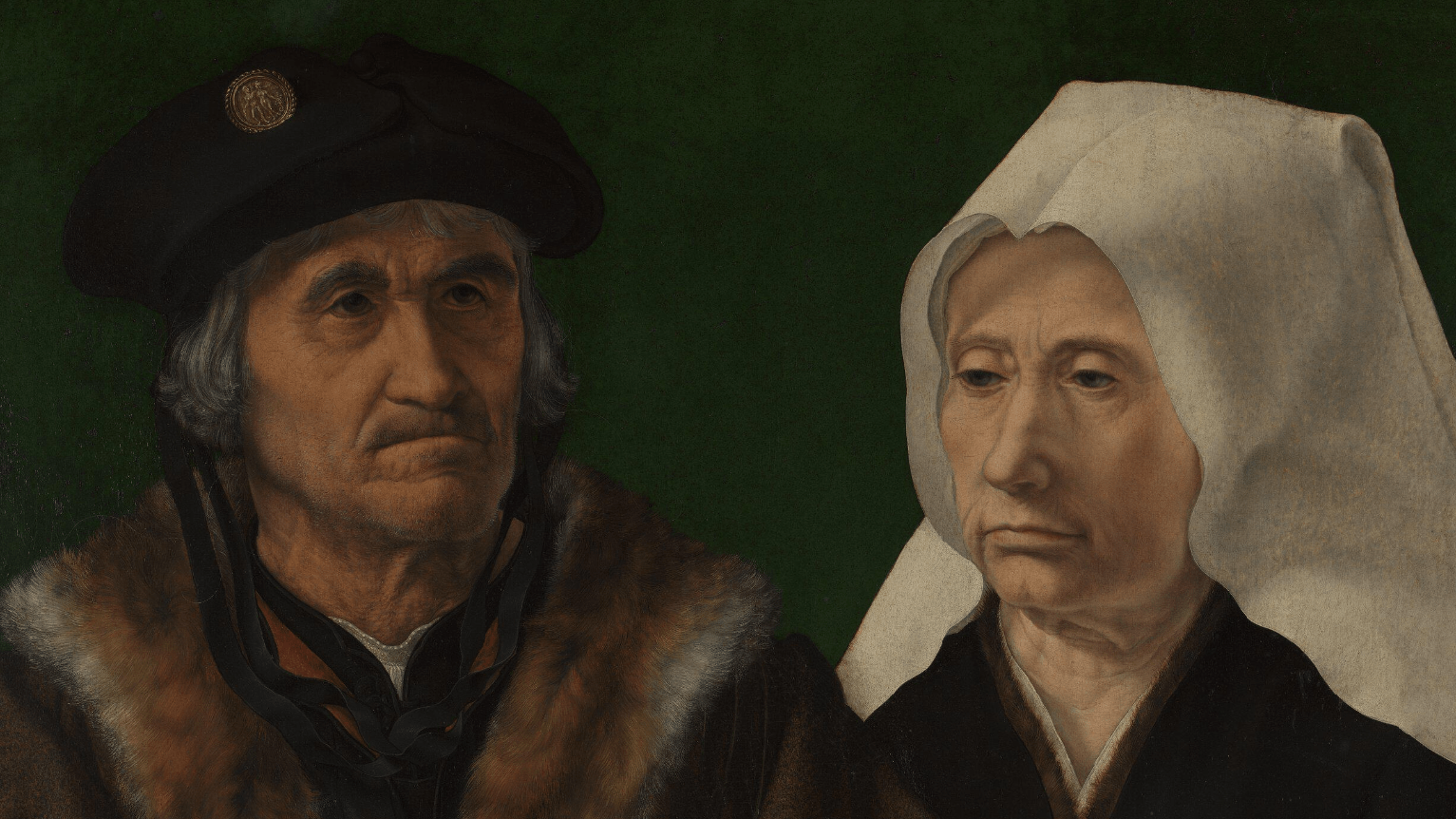

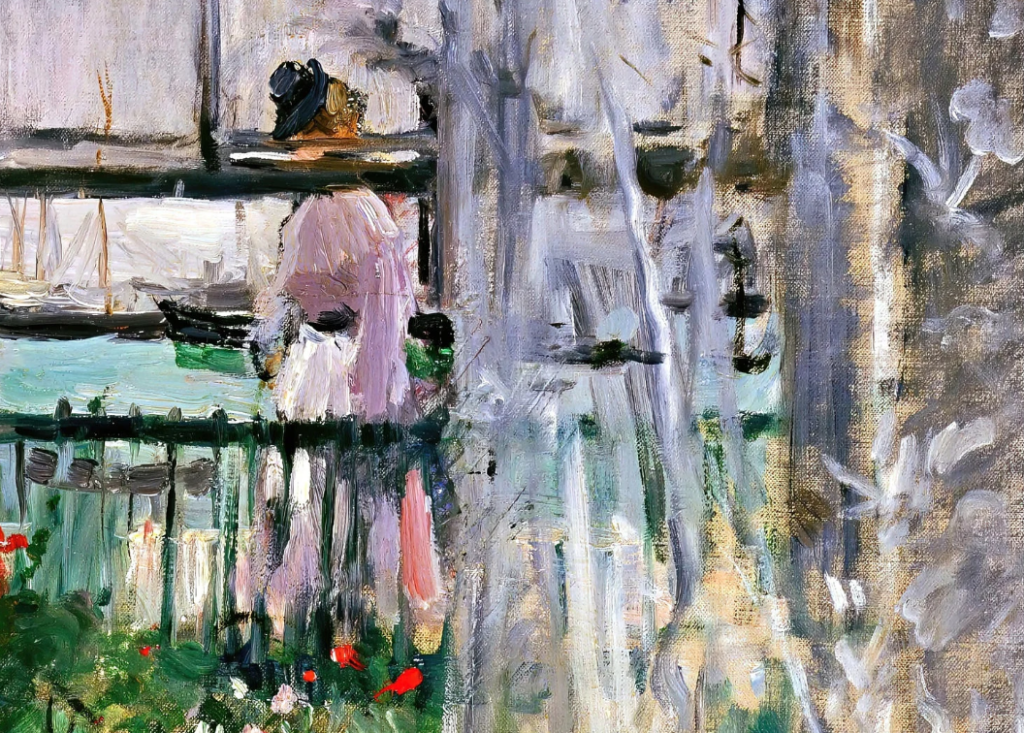

Berthe Morisot, Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight, 1875. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

Last week I talked about a traditional, old fashioned couple, where the man was in the driving seat. This week, we will see woman take the reins: Madame Manet, better known by the name she called herself – as she never let go of the reins – Berthe Morisot. She is the subject of the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s current exhibition, Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism, about which I will be talking on Monday, 24 April at 6pm. If they had staged the equivalent exhibition about one of her colleagues (Claude Monet, you might have heard of him) people would be queueing round the block, but they aren’t, so I can only assume that they don’t know what they are missing. You lot are, however, far more sophisticated, and if you have any sense you’ll hotfoot it to South London in case the hoi polloi find out that she was (a) a far more ardent supporter of the Impressionist cause and (b) arguably a greater innovator.

Thank you to everyone who came to The Ugly Duchess on Monday – and apologies for (and thank you for putting up with) the technical difficulties. If any of you weren’t free, or were, and would like a second attempt at an interruption-free talk, I will be repeating it for ARTscapades on Thursday 18 May at 6pm – I’d offer you all free tickets, but they are a charity, raising money to support our under-funded museums… It’s also worth bearing in mind that they record their talks, so if you’re not free on the 18th, you can catch up with the recording over the following couple of weeks.

After Shaping Impressionism I will talk about After Impressionism at the National Gallery (on 1 May), and the following week head from nature to abstraction with Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian – keep an eye on the diary for what comes next.

The painting shows an interior, although the focus is not on the room itself, but on the outside world, the view through the window. In some ways, the real subject of the work is the act of looking, and, because this is a painting, it is also about the act of painting what we see when we look. Our eyes are directed towards the view by the various framing devices – the window frame, for example, which draws our attention to the exterior landscape in the same way that the frame of a painting gives the art a heightened status and proclaims it to be something worth looking at. The view is also framed, to the left and right, by the gauze curtains which hang down on either side. We are also encouraged to look out by the actions of the man on the left of the painting who, sitting on a chair that looks as if it is facing towards us, turns to look over his left shoulder and out of the window. He functions as a repoussoir – literally, something that ‘pushes back’ – thus ‘pushing’ our eyes ‘back’ to the landscape out of the window. However, the amount of landscape we see is relatively small compared., to the size of the painting – the framing elements take up a lot of space. Although the curtains do not entirely block the view, they do restrict it, and the man’s white jacket enhances the drape’s ability to obscure. The predominantly vertical form of the jacket also echoes the fall of the curtain on the right hand side. There is a similar horizontal pairing, with the wall below the window echoed by the row of small, framed glass panels at the top. It may be the weather, or the fact that there are few features visible in the sky, but at first glance these panes of glass might even appear to be opaque. There are many grid-like elements here – not just the verticals of the curtains and jacket, or the horizontals of wall, window sill and upper row of windows panes – but also the posts and rails of the picket fence which marks the boundary of the garden, the two people on the promenade beyond it, and even the masts (and hulls) of the boats in the background.

If you’ve read the title of the painting then it comes as no surprise to learn that this is Eugène Manet, and that he is on the Isle of Wight. He was an artist, but he was not the Manet – that was his elder brother, Édouard. It is August 1875 (in this painting), and the previous December – the 22nd, to be precise – he had married another artist, Berthe Morisot, who had always wanted to go to England. This is them on their honeymoon. Or rather, this is him on their honeymoon, because she is standing behind the easel painting. What is now known as the First Impressionist Exhibition had taken place in Paris from 15 April – 15 May 1874. Morisot had exhibited alongside Monet, Renoir, Degas et al, and had in many ways ‘arrived’ on the scene – although she had exhibited regularly at the annual salon over the previous decade, so in many ways had ‘arrived’ even before her now more famous peers. What seems to have happened is a commonplace for male artists going back to the medieval times: you finish your training, you make your mark, you settle down and get married.

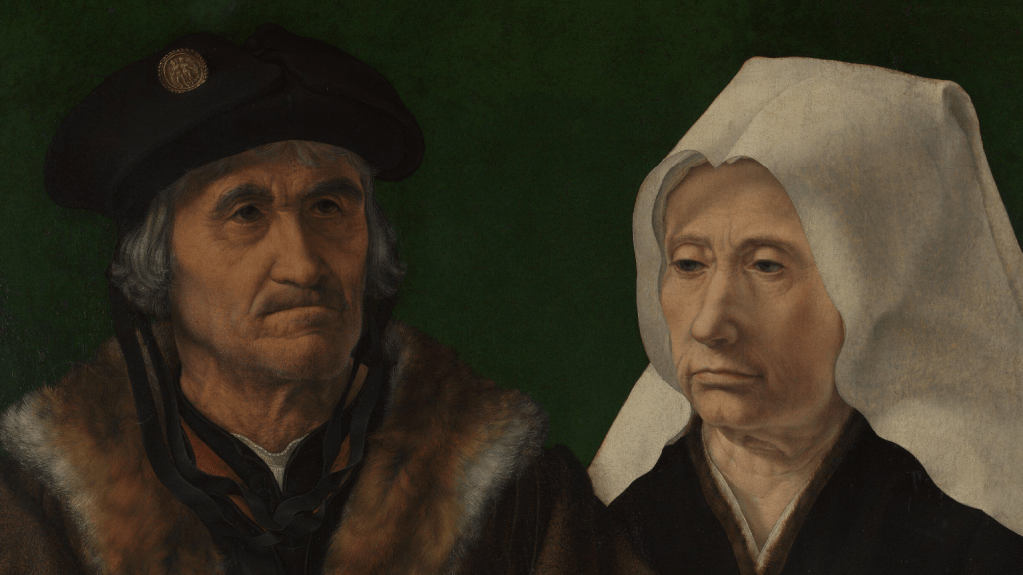

This detail alone shows how fundamental she was to the shaping of Impressionism. Notice how freely it is painted, with the bold, apparently haphazard brushstrokes nevertheless making coherent sense of the shape and structure of Eugène’s jacket. The sunlight shining through the window glances across the front of the collar, shoulder and sleeve, and purple/blue shadows define the unlit sides. This colour choice alone shows Morisot’s mastery of Impressionist colour theory. If sunlight is considered to be a yellowy orange, then the absence of light should be represented by the colours which are opposite on the colour wheel, the complementary colours. Opposite yellow and orange are purple and blue, he colours she uses for the shadows. However, the back of his jacket also includes a lighter peachy colour. There is just a thin sliver of wallpaper visible in the detail above (and just below), edging the left-hand side, but you can see the same peach-coloured paper with orange/red dots under the windowsill in the full painting illustrated above (and in other details below). The light has reflected off the wallpaper and onto Eugène’s back. This explains the peach-coloured brushstrokes: it is reflected light.

The composition is so very specific here: Eugène’s face is neatly framed by the bottom element of the window frame and the top of the fence – allowing him the maximum available view: his view is framed as ours is. He appears to be looking towards the girl standing with her back towards us, although he may well be looking further to the right. The girl herself is depicted on the canvas directly underneath the vertical element of the sash window. Impressionists were ‘supposed’ to be painting what they saw when they saw it, grabbing each moment spontaneously as it came – but that didn’t stop them adding in the artfulness, and arranging things to create richer harmonies: jackets like curtains, hat ‘ribbons almost lining up with the horizontals of the window frames, girls continuing the verticals of the same… that sort of thing.

In the detail above it is clearer that the lower half of the window has been slid upwards (which is, of course, how a sash window works): there are two horizontal framing elements, with the darker one further in, and similarly, there is a lighter, outer vertical element to the right of its darker, inner equivalent.

I read somewhere that Eugène looks relaxed in this painting – but I really don’t agree. The chair faces us, and if he were relaxed, and sitting comfortably, he would be too. But his legs (or at least one of his legs, Morisot is unconcerned about his precise posture) slide over the edge of the chair, and he has to turn through about 120° in order to see out of the window. Not only that, but look at the contorted position of his fingers – the fourth, ‘ring’ finger is buried between those on either side: there’s quite a bit of tension there. And Morisot’s own account of painting him confirms this. She learnt to paint alongside her sister Edma, one of whose paintings is included in the Dulwich exhibition. However, Edma married, and dedicated herself to her family, leaving painting behind. She often modelled for Berthe, both before and after marriage, and the two continued a lively correspondence. During her honeymoon Berthe wrote to Edma from Globe Cottage in West Cowes, on the Isle of White,

“…I began something in the sitting room with Eugène; poor Eugène is taking your place; but he is a much less accommodating model; he’s quickly had enough…”

There is a strong sense that he’d prefer to be outside exploring, rather than being confined to the domestic sphere. You could even suggest that the sketchy style of painting might result from his reluctance to pose for too long. Compare the way in which he is painted in the above detail with the precise focus of the plant pots and their saucers, especially given the brilliant precision in the way the light and shade is defined – notably around the tops of the pots: clearly the plant pots were not in a hurry to get away.

However, this has nothing to do with the willingness or otherwise of the model – it is a fundamental aspect of Morisot’s style. Where precision is needed, she can supply it. If evocation will convey something more eloquently, that is what we see – see below! The plant pots themselves might be models of exactitude, but as for the plants – well, the stems are clear, but the leaves and flowers blend with those of the plants in the garden, and they become indistinguishable. But pictorially, that isn’t a problem. Certainly when looking at the picture as a whole we take it all as given.

The curtain on the right is also the model of Impressionist ellipsis – so much is missed out that is not necessary. The curtain is defined by a few thin white brushstrokes of different densities, which express the depth and positions of the folds. They are either painted on top of the painting of the fence, or of the foliage, or, in the bottom right, over blank canvas. The contrast between the intensity of colour in the garden and the pallor of the curtain over the windowsill could hardly be more marked.

We can see this again towards the top of the curtain. Almost more than any of her Impressionist colleagues Morisot has liberated the brushstroke from its descriptive function, so that dots, dashes and lines evoke the the appearance of the form rather than enumerating each of its material qualities. This detail is also an important indicator of the precision of the viewpoint she has chosen. Just separated from the curtain by a sliver of the landscape is a women in a lavender dress and white apron. She is a woman in service – the nanny of the little girl we have seen before. She has a black belt – which could equally well be a continuation of the boat behind her – and a black hat, which protrudes above the raised window frame. But how frustrating that we can’t see her face. Or is that, in fact, a deliberate choice on the part of the artist?

There is, in fact, a remarkable role reversal in the painting. In Western European society – and indeed in many other societies across the world – it was usually the woman who was restricted to the domestic sphere, while men could travel freely outside. In this painting, whether consciously or otherwise, Morisot explores another possibility: the women have gone out, while the man remains at home. However, it also touches on one of Berthe’s problems as an artist who had, until recently, been an unmarried woman: she wasn’t allowed to go out painting on her own, even if she was just heading to the Louvre to copy the works of others. She had to be chaperoned, just as the little girl is here. Indeed, she even wrote to Edma speaking of her frustration. As a little girl, being chaperoned is not entirely surprising, but as a fully grown woman? At least this girl has the possibility of exploration, and, even given the rapid brushstrokes with which she is painted, we can tell from her clothes that her parents have substance. They can afford a nanny for one thing. Morisot even seems to be showing her awareness that the girl’s future is dependent on the unacknowledged work of a faceless multitude – and maybe that is why the nanny’s face is hidden behind the frame.

However, much of what see derives from the artist’s continued determination to work, and to work unchallenged. There is more than one role reversal here. It is often implied that Eugène gave up his career to support that of his wife, which, if it is true, is admirable, but it does nothing to undermine her own strength of purpose. She certainly didn’t give up her name, and continued to work as Berthe Morisot long after she became Madame Manet. But it wasn’t always easy. When painting en plein air she had a number of strategies to avoid being harassed. For one, she would often start work as early in the morning as possible so as to achieve as much as she could before there were too many people around. The choice of painting the view from the living room was also, in all probability, a pragmatic one. Inside her own space she will not be confronted by curious observers. However, it does mean that she is still constricted to the domestic sphere – even if, in this case, she is the maker rather than the model, an active participant in the world of art, rather than its passive subject.

And talking of subject, I’m am intrigued about the subject of this painting: what is it actually about? What is Eugène looking at? The girl? The nanny? The boats of the Cowes regatta? Is the act of looking out an act of looking forward? Is he imagining the future of his own family? Three years and three months after this painting was finished, the artist’s and the model’s daughter Julie was born, and Berthe would go on to paint the relationship between father and child which few artists – if any – had ever thought to explore. Maybe they are both thinking about that.