Antonio Canova, Psyche revived by Cupid’s Kiss, 1787-93, Louvre, Paris.

So far in my series on sculpture I haven’t mentioned Antonio Canova, although I will this Monday, 20 June at 6.00pm, when I will discuss the very substance of art (or, at least, the different substances from which sculpture is made), in a talk entitled Material: Method and Meaning. As a result, it seems a good opportunity to re-visit one of the posts from the 100 ‘Pictures of the Day’ – particularly as I currently find myself very busy visiting exhibitions in order to find suitable subjects for future talks. When I know what they are I will of course post the details here and on the diary page. This is an ideal post to re-read, as it introduces many of the ideas I will cover on Monday – the materials of sculpture, their qualities, advantages and disadvantages, their ‘meanings’, and the techniques involved in turning them into sculpture. What follows was the 8th post dedicated to just one story – Cupid and Psyche – and if you want to have a look at the others you should start with Day 43 – Psyche – or it might be easier to click on the ‘Psyche‘ archive button, where all the posts appear in reverse order (sorry, I’m really not in control of this website). Meanwhile, at the end of the seventh post, I had left Cupid and Psyche living Happily Ever After… what could follow that? Well, this:

I know, Cupid and Psyche are living happily ever after, but I couldn’t leave them without one last look back, and without one last, truly beautiful image of Psyche. This is a sculpture by Antonio Canova, the great master of neo-classical simplicity.

As often with Canova, there are two versions of Cupid and Psyche. This one is in the Louvre, and was originally commissioned by Colonel John Campbell. He was a Welsh politician and art collector, who, after the death of his father when he was just 15, and his grandfather when he was 24, found himself remarkably well off, and he headed off on the Grand Tour at the relatively late age of 30. He travelled to Italy and Sicily, where he spent the next five years. It was while he was there that Campbell commissioned this sculpture from Canova, who was four years younger than him – 30, when this sculpture was commissioned in 1787. However, it seems that Campbell never received it. Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, acquired it in 1800, and after his death in 1824 it passed to the Louvre. A second version was commissioned by Prince Nikolai Yusupov in 1796. They were a highly sophisticated family. They had a superb art collection, and a rather fantastic palace in St Petersburg, which even had its own theatre. The palace and theatre are still there, but after the Revolution, the Canova ended up in the Hermitage.

I could have talked about this sculpture two weeks ago, when discussing Sir Anthony van Dyck’s Cupid and Psyche [Picture Of The Day 54 – but never edit on a train – I seem to have just deleted this when trying to copy a link, and now I can’t get it back. Ah well…], as the two works represent the same moment – but let’s face it, they are rather different, and both deserve a moment to themselves. We’ve got to the point in the story when Psyche was carrying out the last of her tasks, and had collected some of Proserpina’s ‘Beauty’ to take to Venus, but she opened the container and fell into a death-like sleep. Now Cupid has awoken her with one of his arrows, and they embrace… In many ways, it’s that simple, and the sculpture itself looks effortless. But ‘effortlessness’ turns out to be the result of a lot of hard work. The main aim of neo-classicism was not to be bold, and daring, and original, trying to find new solutions to problems, but to look for something essential, an idea that looks as if it has always been there, and then to pare it down even further, to simplify it and to make it clear. This might appear to be a somewhat disingenuous intention, especially as this particular sculpture manages to be both original and daring. Cupid reaches around Psyche, and, as she sits up, he supports her head in his right hand, while his left goes around her torso. She stretches up to hold his head, her arms forming a loop, in a similar way to his, which curl around her. The two are encircled by each other, two halves of the sign for eternity, promising the continuity to come. She lies on one hip, he kneels, balancing with one foot lower down the rock, her body forming a continuous line with one wing, his extended leg with the other. Their bodies form a pyramid, which, with his wings, becomes a cross – ‘X’ marks the spot. The wings themselves are carved so thinly, and the arms are entirely free from their bodies: this really is daring carving, puncturing a single piece of Carrara marble and turning it into the softest of flesh.

And it is thin – look how translucent those wings are. The excavation of the forms really pays off when Canova’s sculptures are lit well, and preferably, by natural daylight. The light falls on different surfaces, emphasizes some features, and blurs certain boundaries: the play of light and shadow defines everything this sculpture is about, caressing the surfaces, touching the sculpture lightly as they touch each other. But how do you work out such a complex composition? As any couple will understand, it’s not always easy knowing where to put all four arms, and when there are wings as well…

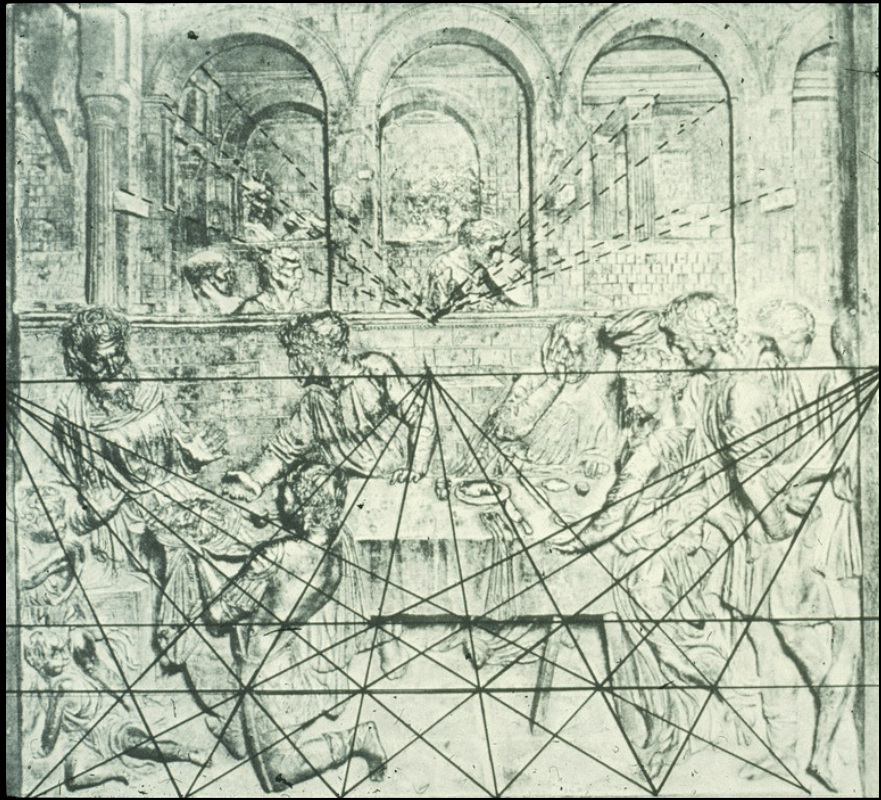

It’s always best to start with a drawing – although that might seem counterintuitive for a three-dimensional object like a sculpture. Canova’s work is conceived to be seen in the round, although there is usually a principal viewpoint. That is what he is developing in this drawing. You can see that the basic composition is already in place: the long curve from Psyche’s right foot – at the bottom right of the pyramidal composition – up to her right hand above Cupid’s head; the fact that her hips are twisted towards us, so we get as full a view of her body as possible; and the framing of their faces by the loop of her arms. We also see the full extension of Cupid’s right leg as he leans over her, kneeling on his left knee, with his left arm reaching around her torso. There is even a sketched suggestion of the drapery underneath her. The only thing that Canova was to change was the position of the wings. In the drawing they spread out across them, almost like a protecting canopy. They are more horizontal than in the sculpture, where they are far more awake and alert. You could even argue that in the drawing they represent Psyche’s lethargy, whereas in the sculpture they are far more vital: they are Cupid’s wings, after all, and reflect his energy at this point in the story. They also come to have a more defining role in the composition, with its overlapping diagonals, continuing the lines of the two bodies, and bringing the couple together.

Having decided on your basic compositional structure on paper, you then have to check that it would really work in three dimensions – hence the use of clay. Often the small clay models were fired – thus making them terracotta – which meant they could be kept. There was always more than one reason to do this. Canova was aware that a sculpture could only be owned by one person – but that it was always possible to make a second version. So it was enormously useful to hold onto all of the developmental stages in case you wanted to go back and reassess the finished product. The best place to see this is the Museo Canova in Possagno, the small town in the Veneto where he was born, which has a remarable display of sketches, working models and plaster casts. Another reason to ‘save’ the bozzetto (POTD 42 & 51) was that Canova, like many artists since the 16th century, was very well aware of his development as an artist, and the process of evolution of each individual piece – and that the process itself was saleable. Terracotta bozzetti were collectable in a similar way to drawings.

However, looking at the bozzetto above, you realise pretty quickly that this is not the finished composition. It is the female figure – Psyche – who is sitting more upright, and has the male – Cupid – in her arms. Although one of his legs is extended, and the other bent, he is sitting on the ground, rather than kneeling. It is more as if she is caring for him, rather than him waking her up. Indeed, it could be that this predates the drawing – and that, when commissioned to carve a sculpture showing Cupid and Psyche, Canova originally thought of a different episode in their story: this looks more like Cupid swooning – although without the wings. They really would be tricky in clay. It could be that he abandoned his idea, and went back to the drawing board – so the drawing might have come after this terracotta. That aside, it does at least show you what the process of development would be: the creation of a rough, terracotta model of a potential composition. The limbs are built up with small pieces of clay, and modelled by hand, or with a number of different tools. The most obvious here was something like a comb, a toothed spatula, which has been used to scrape the base into its current form. There could easily have been several bozzetti like this. Each would not necessarily have taken too long to make, and, being clay, were relatively cheap. Clay is also extremely malleable, so adjustments can be made as you look, and, working on a small scale, you can turn the model around in your hands and check every angle to see that all possible viewpoints work. In this way you would eventually arrive at a definitive composition. The next stage would be to turn the bozzetto into a stone sculpture.

Having decided on the composition, and how it would work in every detail, Canova would then make a full-scale model in plaster. This one was made for Prince Yusupov’s sculpture – as I said, the sculpture itself is in the Hermitage in St Petersburg. However, the plaster modello has ended up in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It might look as if it is not in a terribly good condition – or that the complexions of both Cupid and Psyche have suffered from some terrible skin disease, as it is covered all over in small spots. These are, in fact, metal pins, which have been inserted into the surface of the plaster, and there are more pins where the surfaces are more complex – notably on Cupid’s left hand, just below Psyche’s breast. These are measuring points for the stonemasons. Yes – Canova didn’t carve the marble himself. Don’t feel disappointed – the same is true of many, many sculptors. Rodin did not carve The Kiss, for example, and even Bernini had a helping hand with the leaves on Apollo and Daphne (POTD 56). The stone masons were expert at replicating the precise appearance of the modello, as it was primarily a mechanical exercise. To do this, they used a pointing machine, which measures the height, depth and distance from left to right of each pin that has been inserted, and helps them carve the marble to the same depth at each point. If you’d like to see how it works, there is a good video from the Smithsonian Institute, Carving a Marble Replica using a Pointing Device – other longer videos are available!

However, this process does not complete the work – it is just roughing out the forms – the finish would have been done by Canova himself, and he insisted on doing this in private, so that no one could see his secrets. How, precisely, did he get that wonderful silky finish? That’s where the real skill lay…

I’m including this photograph as a real lesson in looking at sculpture. It is solid, it is three dimensional, and you can move round it. But all too often, with Canova especially, people only bother to look at the ‘front’ – they never get beyond the ‘principal viewpoint’. It was only when I went round the ‘back’ of the Three Graces that I realised what a brilliant artist he was – he has thought about every point of view. There are several clues to that in this photo. It is only from this side that you can see the vase lying behind Psyche that would originally have contained Proserpina’s ‘beauty’ – and lying next to it, to the right, and pointing towards her, is the arrow that Cupid used to wake her. It is only from this angle that you can see his quiver, for that matter, still full of arrows – that crowd is lucky he’s busy at the moment or there could be mayhem. And quite apart from those details, the sculptural mass of the composition, the way the two forms stretch in towards each other, his, taut and leaning down, hers, limp but reaching up, can only be appreciated fully from this side, without the complexity of the interlocking arms and the incidental distractions of their faces. And here’s the real clue: just under her right foot, projecting beyond the base, there is a handle sticking out, and that would originally have been used to turn the sculpture round. OK, so now there is no one to turn the sculpture for you, and you have to make the effort yourself, but do. Walk around, look at every possible viewpoint, get closer and further away. And never worry about going round ‘the back’. You might learn something.

Inevitably I will look at the backs of other sculptures on Monday – including The Three Graces – but I will also look at many different materials – from bronze and wood, to ivory and alabaster. I do hope you can join me then.