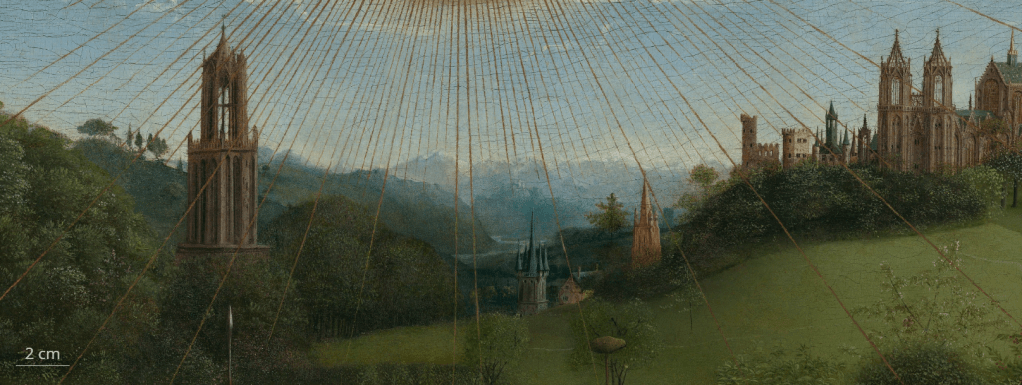

So we come back a day later, and Peter, James and John are still asleep. We are now outside the Garden of Gethsemane, looking in through a gate. This gate – or equivalent – is a common feature of depictions of the Garden, as you will see if you have another look at the relief carving in Tilman Riemenschneider’s Holy Blood Altarpiece, which I linked to yesterday. It is depicted on the wing to the right of the Last Supper, and the gate can be seen – with people coming through it – in the top right. As it happens Jesus is kneeling at the foot of a very similar rock to the one we saw yesterday. Back in our painting, we can see that one of the horizontal bars of the gate casts a shadow on the grass on the other side. At least, I assume that’s what it is, although as the sky is so cloudy in this part of the painting a shadow would seem unlikely – so it could be a pentimento showing through.

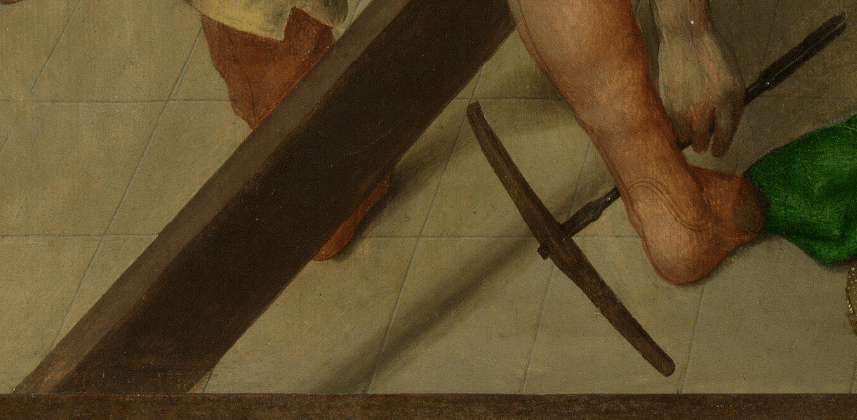

A path winds through the garden, the regular footfalls having worn away the grass. The gate bars the entrance to the garden in a dip, or at the foot of a hill – the bush on the right means that we can’t quite see the lie of the land here. In front of it we see the shaft of the potentially-giant spear which we saw yesterday, but there is still not enough context to determine its true size.

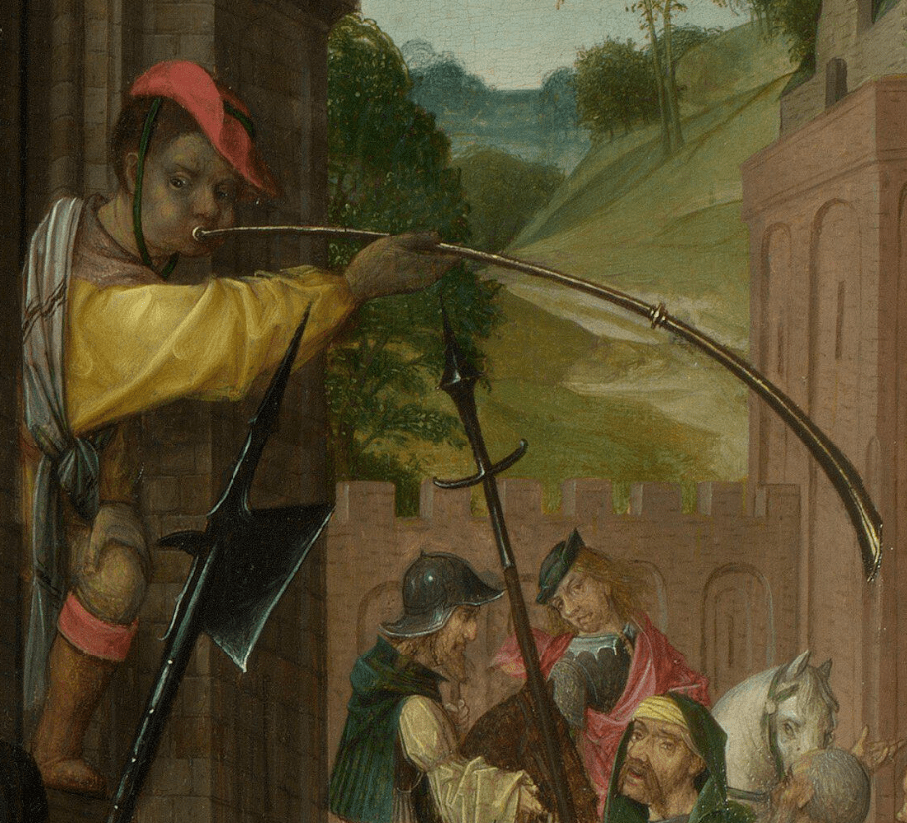

Outside the gate someone stands and points towards Jesus, whose legs can just be seen at the top right of the detail, wearing the same grey/black robe we saw him in yesterday (of course it’s the same, this is the same bit of the painting). I’ll come back to that robe another day. The truly unnerving thing about this detail – for me at least – is that the person who is gesturing towards Jesus can only be Judas, and yet he is dressed in the blue robe and red cloak that we would associate with the man he is about to betray. If we didn’t know that Jesus is in the background, we would assume that this is him. I cannot explain why Judas is dressed like this, although I suspect it might be something to do with the structure of the workshop which produced the painting – more of that another day, too. That aside, I love the slight shock – the frisson, even – that seeing betrayer dressed as betrayed gives. It is almost sacrilegious.

Yesterday I ended with Jesus’s prediction, ‘behold, he is at hand that doth betray me‘. The verse which follows in Matthew’s Gospel (26:47) proves, of course, that he was right:

And while he yet spake, lo, Judas, one of the twelve, came, and with him a great multitude with swords and staves, from the chief priests and elders of the people.

Judas gestures towards Jesus with his right hand, but looks over his left shoulder. Maybe he is looking towards the ‘great multitude’. His left hand is not visible – it is cut off by the tree which frames the left-hand side of this detail. It’ll be interesting to see what this ‘great multitude’ looks like. If you don’t know where we are yet (and don’t worry, there really is no reason why you should) – and even if you do – it might be interesting to imagine how they will appear.