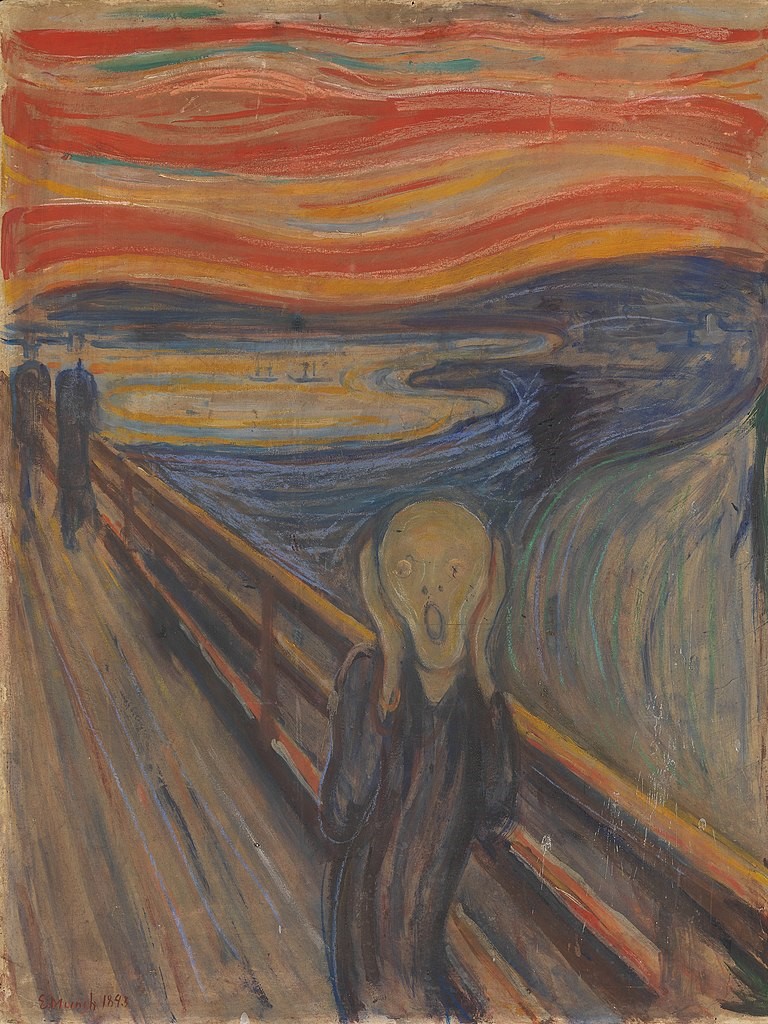

Barbara Hepworth, Pelagos, 1946. Tate.

As so often, things have turned out to be more complicated than I expected – and that refers not just to today’s post, but also to what, exactly, I’m going to be doing in September. This much is settled: on Monday 22 August I will be giving a talk entitled Negative Spaces 3: Barbara Hepworth, as an introduction to the work of one of Britain’s greatest sculptors, and in parallel with the superb, touring exhibition Life and Work which is currently at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. The following week, I will return to the Dulwich Picture Gallery, with Women Looking 2… Then, as I’m not sure what September holds, and I’m not sure how much travelling and seeing I’ll be able to do, I am going to revive a 4-part course I did for the National Gallery a while back. This will be different to my usual Monday talks, as each one will last 2 hours: for the four Mondays in September, (starting on the fifth) I aim to talk about Almost All of Michelangelo. You can find links to book for each individual talk on the diary page… But for today, I would like to look at one of my favourite Hepworth sculptures, and maybe untangle the strings that tie her to Naum Gabo, the subject of last week’s post.

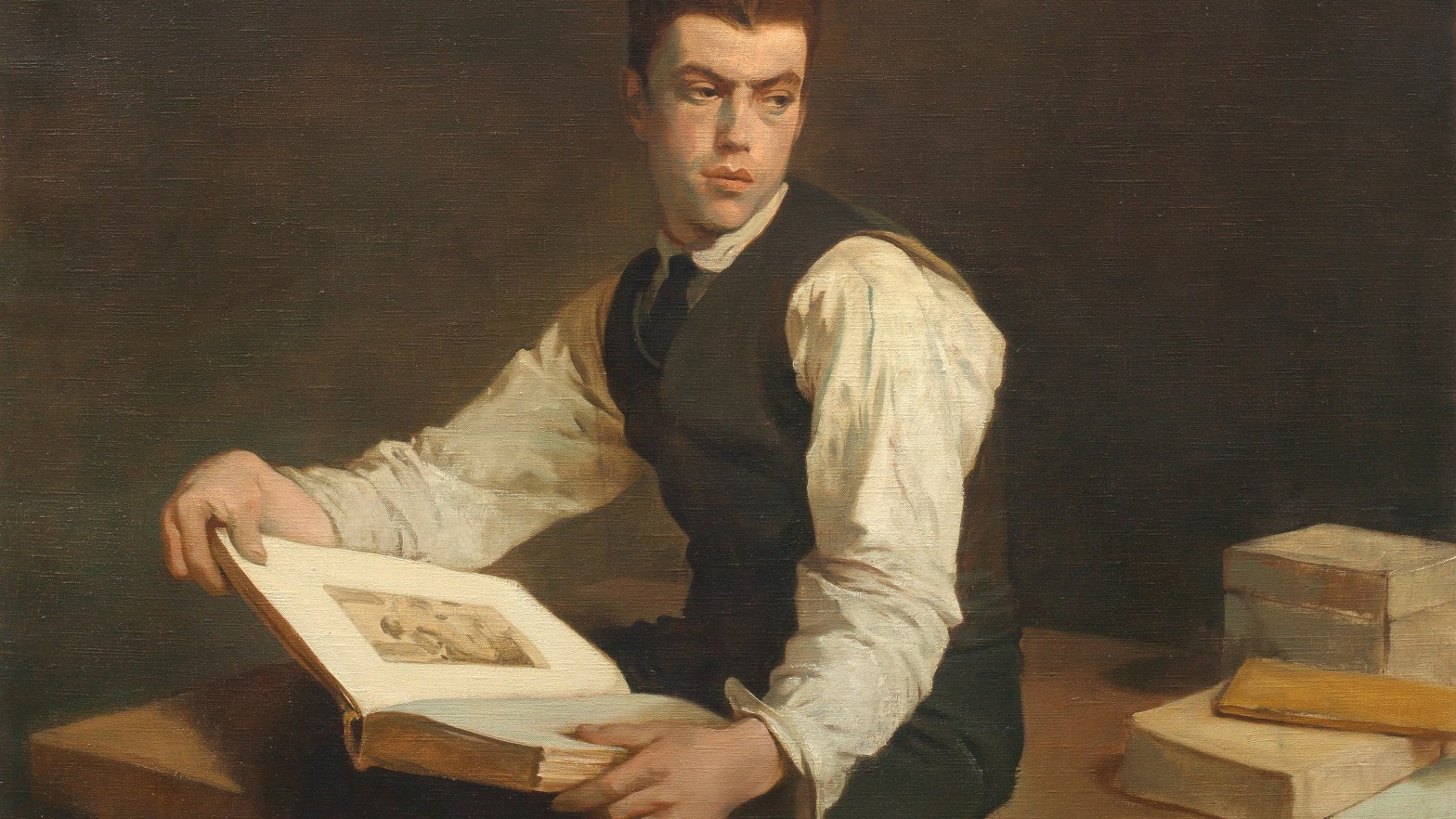

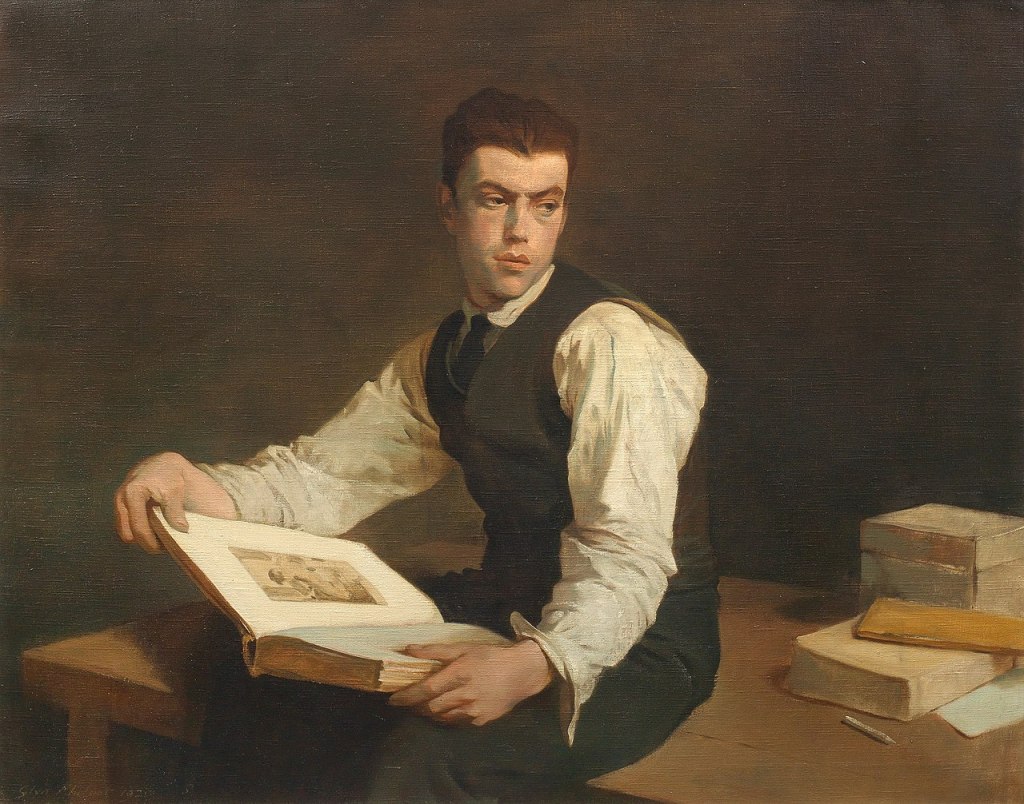

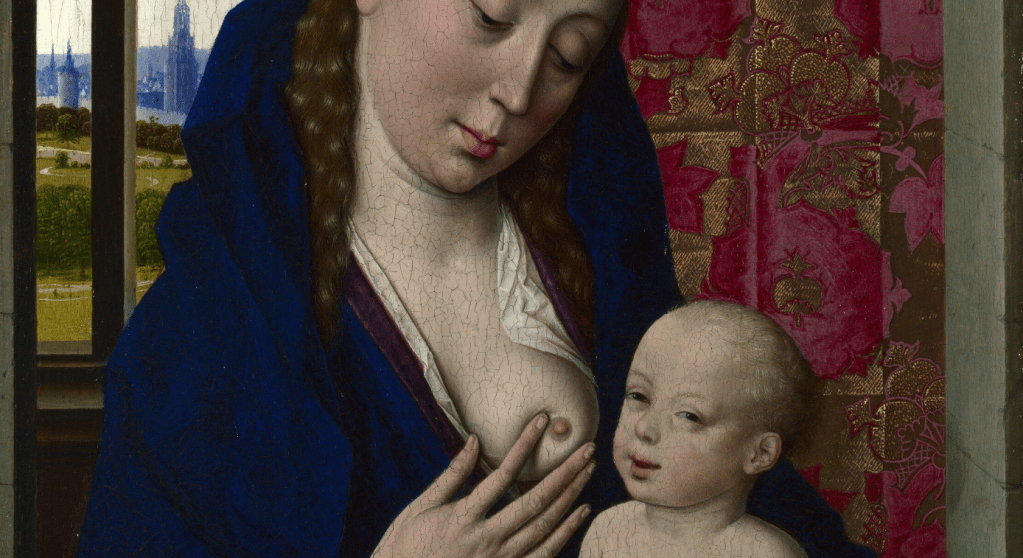

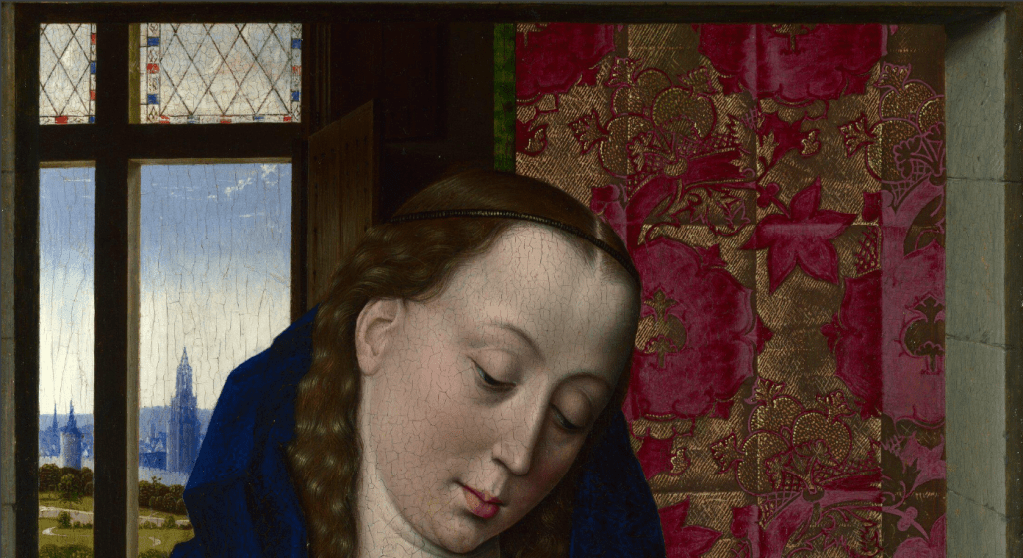

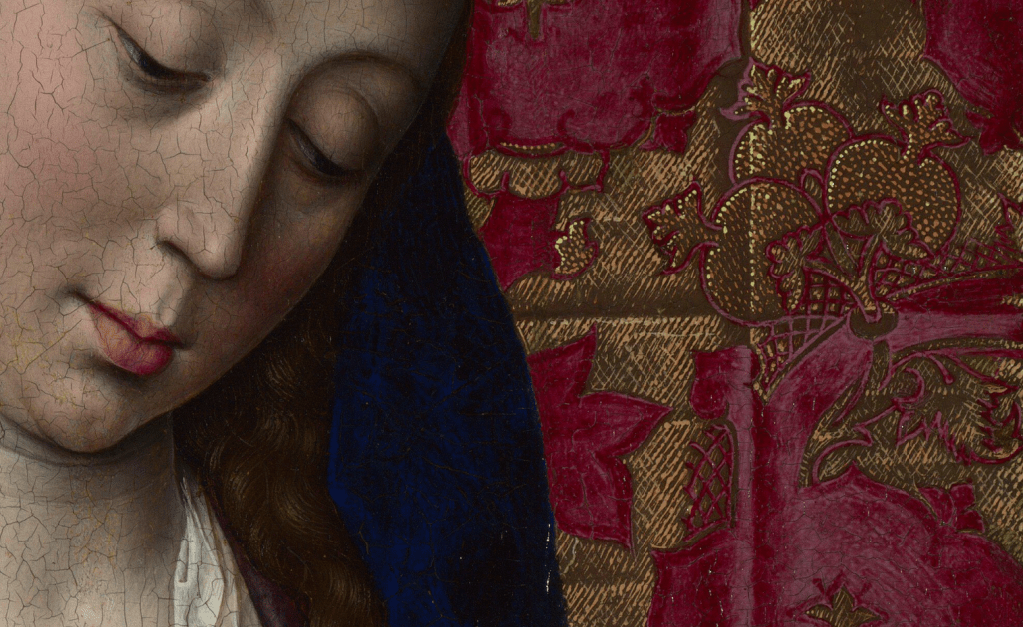

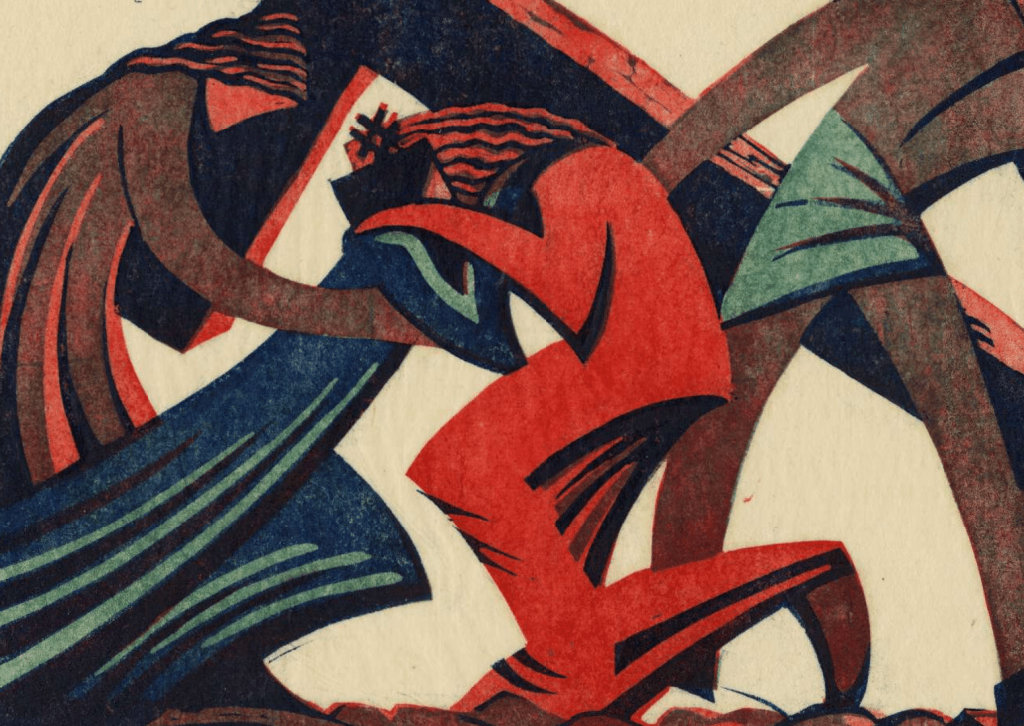

I’d like to start by taking you on a walk around the sculpture, without telling you anything about it, apart from what I see. Admittedly this is led by what I already know is there, but I’ll try to keep my observations to the purely visual. The title, Pelagos, is in the heading above, but I will tell you that Pelagos is one of the Greek words for ‘sea’: this might influence your own interpretation of what we are looking at, which I would strongly encourage. In some ways I want to try and approximate the possibilities of ‘slow looking’ – and at each stage you might want to consider what images or ideas – if any – the sculpture evokes for you. Starting, almost at random, from this particular viewpoint (above), we can see a hollowed out form, which is more-or-less spherical, sitting on top of a rectangular wooden base. As it happens, it is ovoid, but we’d probably need to measure it, or move around (as we shall), to make this clear. Like the base this ovoid is carved from wood, which is left visible on the exterior, while the interior is painted a light colour – white, or bluish-grey. There are two projections, or arms, which curve around, with squarish, but rounded ends. They are joined together seven times by a string which is threaded through holes in the two ‘tongues’.

Moving to our right – anti-clockwise around the sculpture – it is perhaps more obvious that the arms are carved out of a single form, but presumably have a gap between them. Seen square on to the long side of the base, the arms reach the same distance across the central void. The exterior of the ovoid is polished, but not highly: it has a matte sheen.

The arm which is further back here is far more curved than the other, which is why it appeared lower down in the previous image. The grain of the wood and its sheen are more evident here.

Seen flat on to one of the short sides of the base, it is clearer that the two arms are curling round and in, and the distance between the two – which is not that great – becomes more obvious. What I described as the ‘lower’ arm is also the ‘upper one’, the result of its greater curvature – the other arm is far more ‘open’, or less curved. The long diagonal formed by the light interior – from top left to bottom right here – implies that the right side of the sculpture (seen from this point of view) appears more open. At the top, between the arms, the paint looks to be pale blue, whereas below and to the right it looks lighter: this is presumably the effect of the shadow higher up.

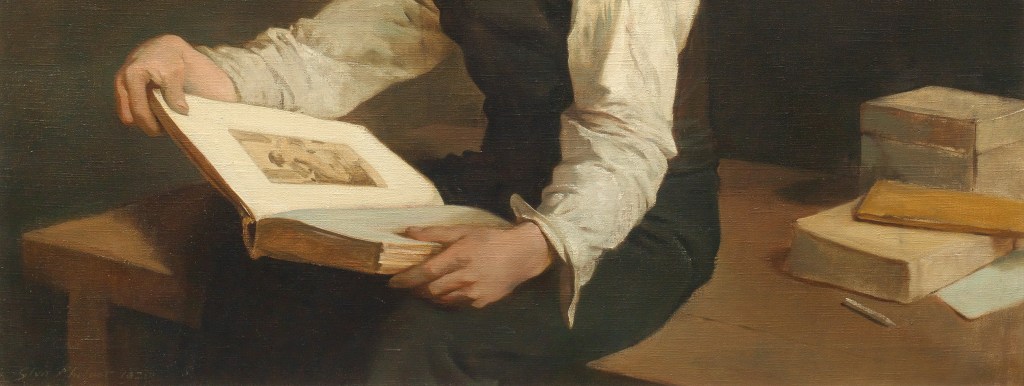

This side of the sculpture is indeed more open, and the painted interior forms a backdrop to the wood of more convoluted arm. The smooth curves of the interior overlap to create a point: remember this in relationship to the drawing which I will show you below.

Seen flat on to the second long side of the base, the negative space created by the two arms takes on its full value, and could be seen as being held in place by the arms. The more open one is hardly visible here, although the strings indicate its position. The more convoluted arm defines three concentric loops – the wooden exterior, the border between the wood and the paint, and the negative space within the paint. It has to be said that Hepworth herself might not have been too keen on these particular photographs – placing the sculpture against a plain, white background takes away the value of the space: something should be seen through every hole. She frequently photographed her sculptures – even the wooden ones – in her garden, thus giving them a place in the world and in our appreciation of it. I’ll leave the last two images for you to describe for yourselves.

More about the physicality of the sculpture: the materials are given, both on the Tate website and in Eleanor Clayton’s superb book Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life (which accompanies the exhibition) as ‘Elm and strings on oak base’. There is no mention of the paint, even though a work from more-or-less the same period, Wave, is described as being made of ‘wood, paint and string’. The paint was originally pale blue, which presumably relates to the title, Pelagos, or ‘Sea’. However, Hepworth often had problems with blue paint, as it often faded. In the end she decided that the matte quality of the paint was more important than the colour, contrasting as it did with the sheen of the wood. At one point the interior was even repainted white. Eleanor Clayton, who is also the curator of the exhibition, tells us, when speaking of Wave, that, ‘The strings are fishing line, connecting materially with the sea and the human community whose livelihoods are bound up with this elemental force’. Given that our sculpture is also called ‘sea’ – albeit in Greek – I am sure that fishing line was used again. It is undoubtedly relevant that Hepworth was living in Cornwall, and near to the coast, at the time the sculpture was made. She described the view from her studio, ‘looking straight towards the horizon of the sea and enfolded (but with always the escape for the eye straight out to the Atlantic) by the arms of the land to the left and right of me’ – which makes Pelagos look less like an abstract sculpture than an accurate description of the landscape. Indeed, Hepworth description was completed with the phrase, ‘I have used this idea in Pelagos’.

In addition to this landscape-inspired interpretation of the sculpture, a statement written for a retrospective exhibition of her work in 1954 – eight years after Pelagos was made – includes Hepworth’s summation of three different ‘types’ of sculpture which had long been important to her. Of these, the third was,

… ‘the closed form’, such as the oval, spherical or pierced form (sometimes incorporating colour) which translates for me the association of meaning of gesture in landscape; in the repose of say a mother & child, or the feeling of the embrace of living things, either in nature or in the human spirit.

So, as well as being an image of the landscape, it is also an expression of the relationship between people. Perhaps the two arms of the sculpture could be seen as two arms reaching around a central space, embracing a void – like the gap that parents feel when children leave them. Look back at the pictures above – there is one I find particularly reminiscent of a ‘mother & child’, and I’d be interested to hear if you see that too. But where do the strings fit into this? Well, we all have invisible ties to people and places. Hepworth herself stated that they represent ‘the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills,’ but, like everything else, they are open to more than one interpretation, and refer to more than one ‘tension’. It is all, in some way, related to our experience here on Earth. For this very reason, the base is important. It is not a subsidiary element, but an essential part of the sculpture – the ovoid form, the arms, the strings – everything is seen in relationship to this flat rectangle, everything is part of a specific environment.

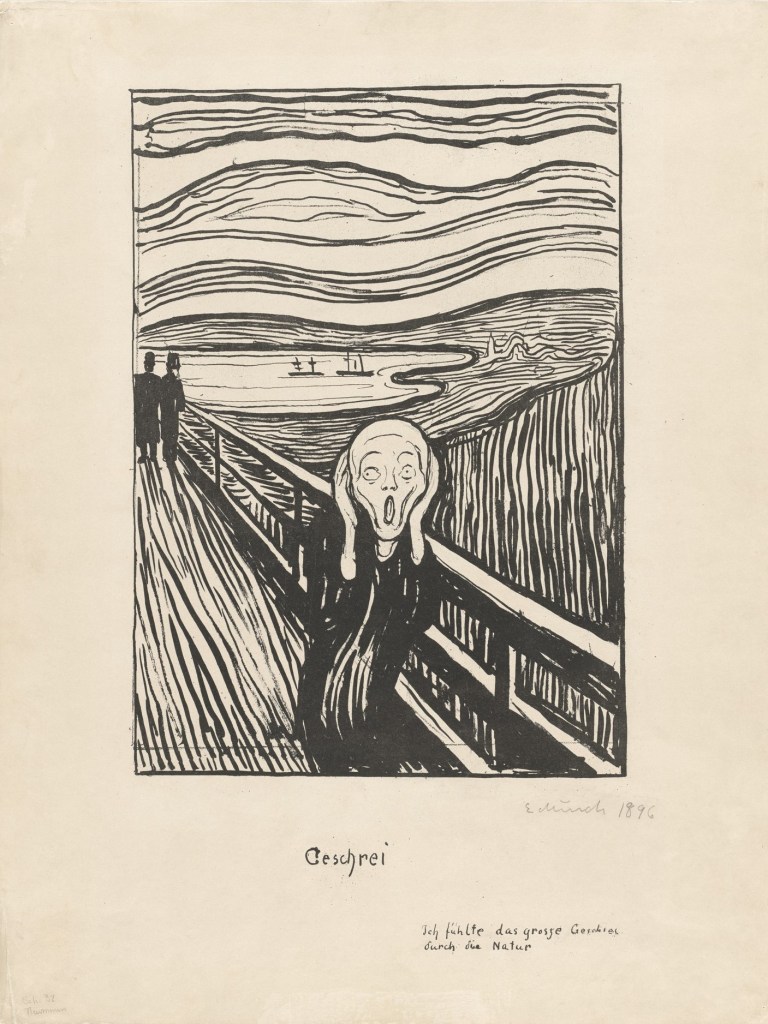

And what of the question hanging over from last week? What is the relationship to the work of Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo? Well, it’s simply the string really. As I said last week, Gabo arrived in London in 1935, and moved to Carbis Bay in Cornwall shortly after his friends Barbara Hepworth and her husband Ben Nicholson moved there in 1939. It was at that point that he started using nylon thread in his sculptures. The first was Linear Construction No. 1 of 1942-3. I included an illustration last week, but here it is again for good measure.

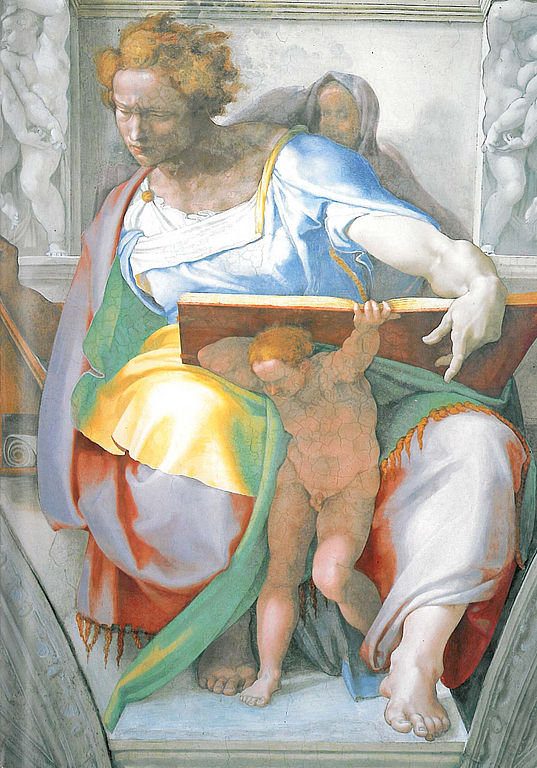

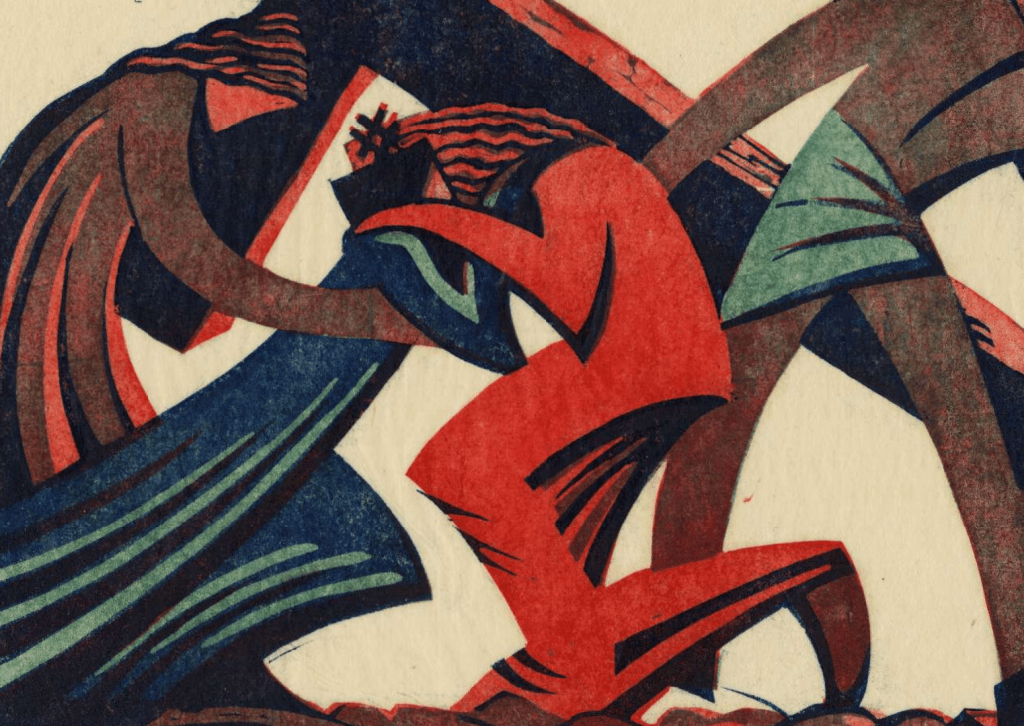

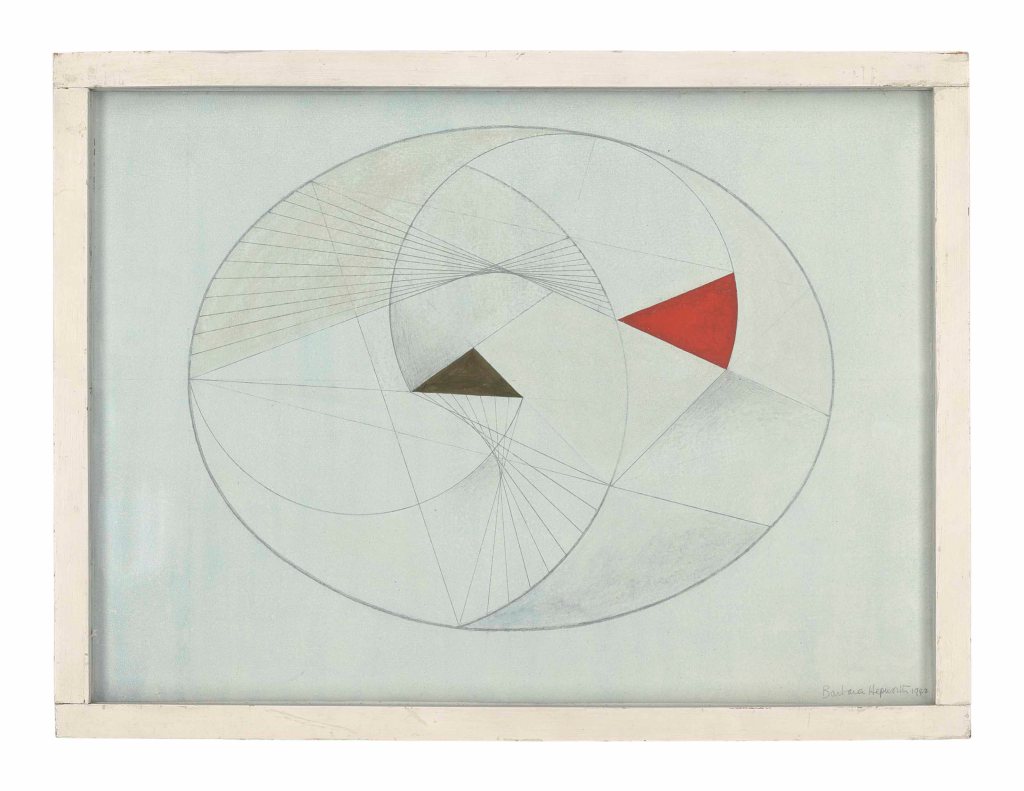

There are several versions and variants of this piece, all of which seem to have more or less the same date. It is called ‘linear’ construction, because of the straight lines made by the nylon filament. Seen together, these become tangents to a virtual curved line. In the 1930s Hepworth and Nicholson became active members of the European avant garde, and became particularly associated with the Constructivist movement. In 1937 the book Circle: International Survey of Constructivist Art was published in London. Its editors were none other than Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson, together with architect Leslie Martin, while Hepworth designed the layout, as well as being responsible for the production of the book and writing one of the essays. At the time her sculptures had names like Three Forms (1935), Ball, Plane and Hole (1936) and Pierced Hemisphere (1937) – entirely abstract titles. On moving to Carbis Bay in 1939 things started to change. In part, this was the result of the war – materials were not readily available, and she was left with full responsibility for looking after her four children, leaving precious little time to work – and precious little material to work with. When she could grab a moment she would draw. Here, for example, is Oval Form No. 2, from 1942:

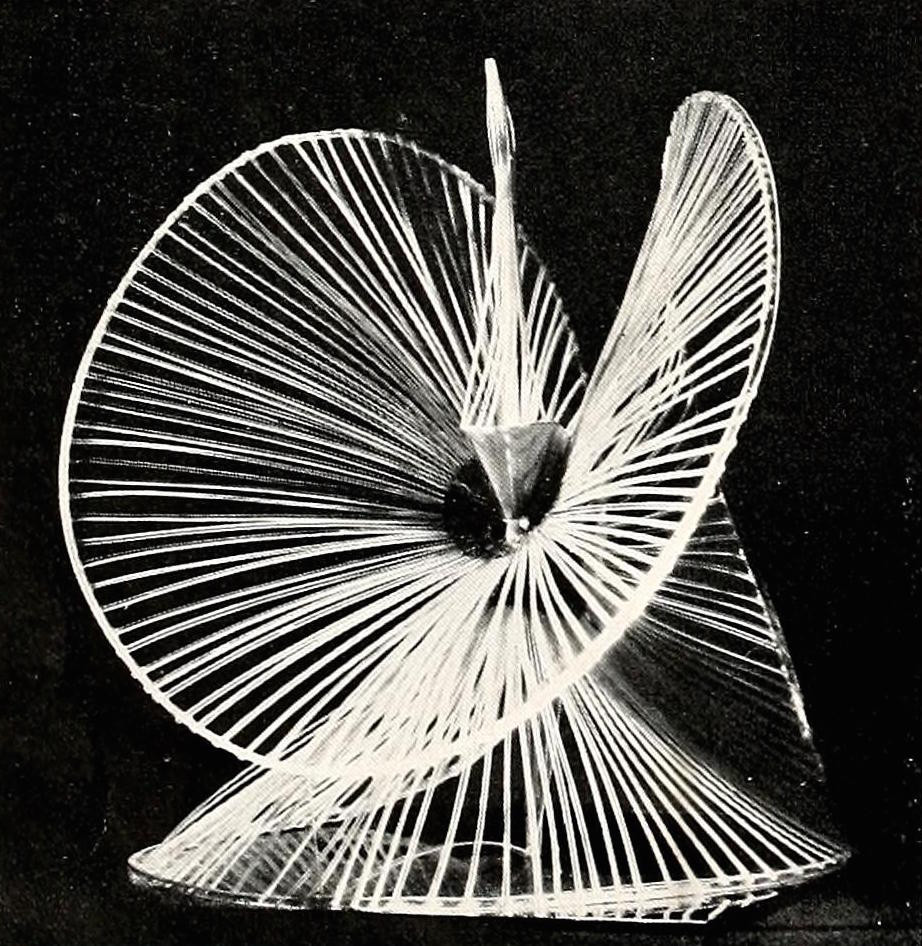

Many of the drawings executed at this time were titled Drawing for Sculpture. These were not plans for sculptures as such, but explorations of the possibilities of three dimensional forms. I have chosen this example because it considers the inner geometry of an oval, as many of them do. If you look back, you’ll see that some of the overlapping curves in this drawing are not unlike some of the views of Pelagos above. Notice how, in a Constructivist way, she builds the drawings from separate lines and geometric shapes. Notice too, that two of the curves are constructed from overlapping straight lines. There is every possibility that this work precedes Gabo’s sculpture (the drawing is dated 1942, Linear Construction No. 1 is 1942-3), rather than being inspired by it. As it happens, there are plenty of drawings from 1941 using similar ideas. And anyway, Hepworth used string for the first time in a piece called Sculpture with Colour (Deep Blue and Red), which she completed in 1940. So maybe it is not Gabo influencing Hepworth, but the other way round? However, I should show you two other works, both by Gabo: Sphere Construction of a Fountain and Construction in Space (Crystal), dated 1937 and 1937-9 respectively.

The former, as far as I am aware, has not survived, while the latter is just about holding on in the Tate collection. Gabo used new materials, not all of which have stood the test of time. Cellulose acetate in particular – from which these two were made – is not as stable as was initially believed. Both use threads of some form. Gabo had also incised lines into his plastics. He didn’t start using nylon thread until 1939, perhaps, but ‘lines’ had been an element of his work for some time before this. What we are seeing is a shared idea, a common interest, a new way of defining space through line, and, as in one of the interpretations of Pelagos, the fact that both Hepworth and Gabo used ‘string’ of one form or another is as much an indicator of their artistic relationship as anything else. However, it is also an indicator of the differences between them. Hepworth was profoundly affected by living in Cornwall, and, having been an avid Constructivist in London, in 1946 she wrote to her friend Margaret Gardiner, ‘I hope my work will always be constructive but I don’t want to be called a “c-ist” any more than “Nicholson”’. By the time she was fully settled into Cornwall, the titles of her works changed: Wave (1943-4), Landscape Sculpture (1944) and Pelagos (1946) are just three examples. Her art was always part and parcel of her lived experience – hence the title of Eleanor Clayton’s book and exhibition – and that applies to the works with abstract titles as well as those with more lyrical, picturesque names. And there are plenty more! On Monday I’m planning to talk about several which are not in the Edinburgh exhibition, hence my comment in the first paragraph that my talk is ‘in parallel’ with the exhibition, rather than an introduction to it, as other talks in this series have been… just so you’re warned!