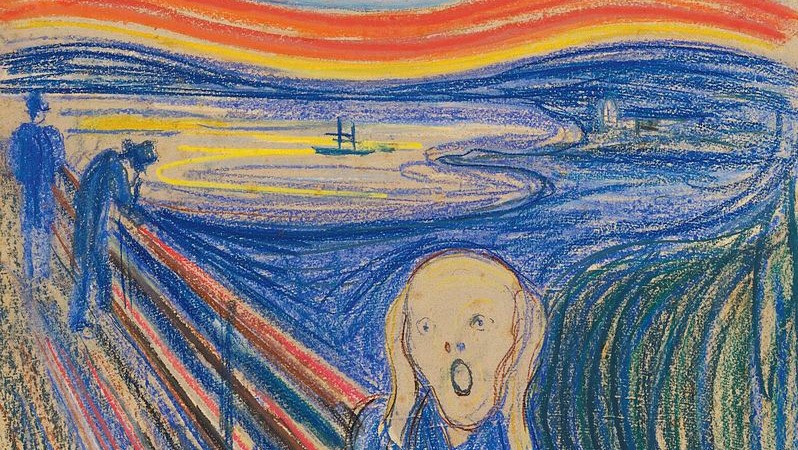

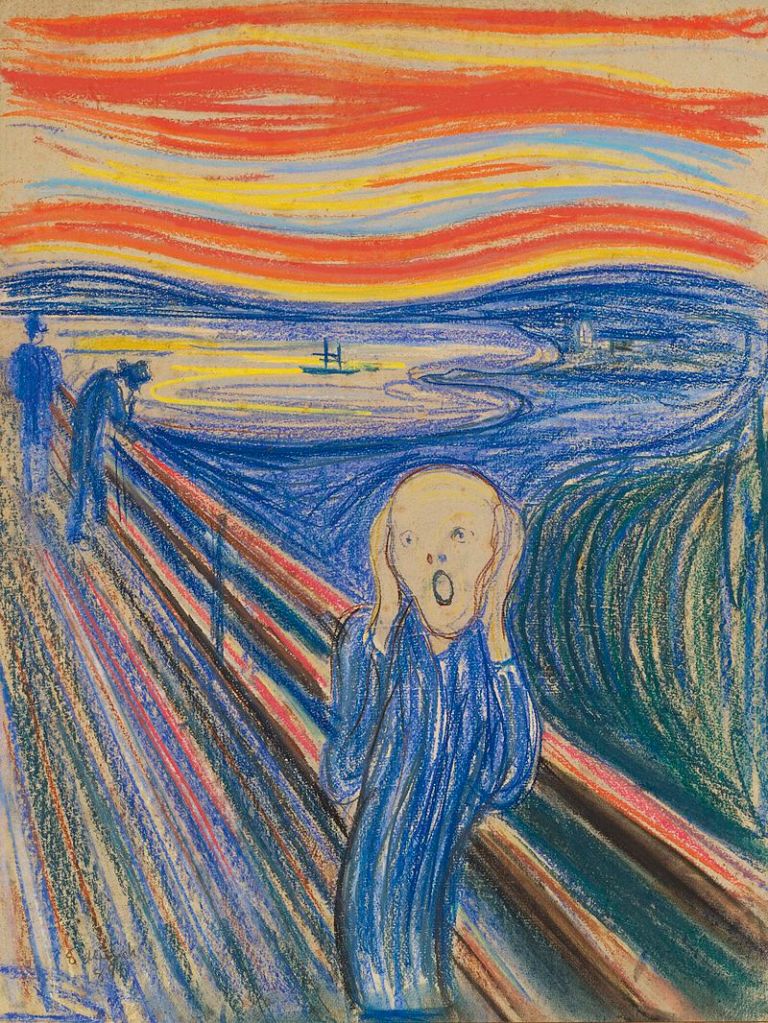

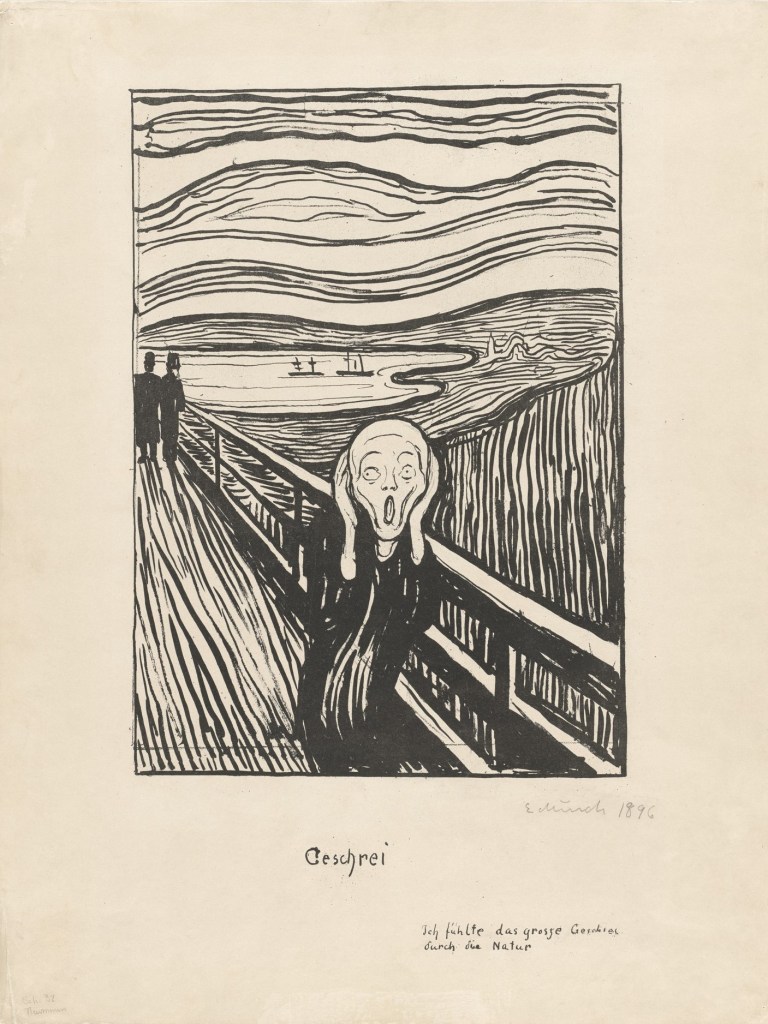

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1895. Private Collection.

If you think I’m being rude – or insensitive – I should point out that the title of today’s post is simply a quotation, in English, from the words that Edvard Munch himself wrote on the first (or second) version of The Scream. An infrared photo of the offending text is at the very bottom of the post, if you want to check it for yourself… There are several versions of today’s painting – two in paint, two in pastel, and a lithograph which survives in a number of different versions, some coloured, some not. I am reposting this entry today as an introduction to the talk I will be giving on Monday 21 April, Edvard Munch Portraits, introducing the eponymous exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Sadly the exhibition doesn’t include today’s work, even if you could argue (at a stretch) that it is a form of psychological portrait… but that’s not the point of the exhibition. The talk will be the second of three looking at exhibitions currently on show in London. The third will be Evelyn de Morgan: The Modern Painter in Victorian London (which has just opened at the Guidlhall Art Gallery) on 28 April. After this, I am devoting May to German art from the 19th and early 20th centuries, starting with German Romanticism (5 May), and then The Nazarenes (12 May). I will also cover German Impressionism (19 May) and the series will conclude with a talk focussing on the sculptor Ernst Barlach (details still to be defined) – but all that will find its way to the diary before too long.

The Scream is one of those images which needs no introduction, so familiar are we with it, and with all the versions, mainly satirical, that it has spawned. Let’s face it, it’s the only painting I can think of that has inspired an emoji 😱, and the film franchise, Scream, uses the protagonist’s face for the mask worn by the killer. Like the many pastiches of Munch’s masterpiece, this franchise is a ‘comedy’ hommage (French pronunciation) to the slasher genre it apes. I’m sure the irreverent approach is just a means to undermine the darker implications of the painting. It is so familiar, perhaps, that we no longer look at it properly. We think that we know what is there, and we just stop looking: familiarity breeds disregard. So let’s look again. I’m going to focus on Munch’s third version of the subject, the pastel painted in 1895, but will consider the development of the series (briefly) below.

When you look at this image (and try to look at it as if you’ve never seen it before), what is the first thing that you notice? My first response, when I started thinking about this post, was surprise at the brilliance of the colour. The colour is why I’ve chosen this particular version to focus on – the others have faded, or were, in any case, duller. The sky is an intense vermillion, the bold, wavy lines interspersed with buttercup yellow and a couple of bands of pale blue. It takes up just under a third of the height of the painting, with a clear horizontal line in a darker blue marking, as the adjective suggests, the horizon. The lowest band of the sky appears to be made up of undulations of this darker blue – although reference to other versions imply that these ‘undulations’ are based on distant hills, blue as a result of atmospheric perspective. The majority of the land and sea is formed from a mid-toned blue, although small amounts of the reds and yellows creep in, in the same way that there is some blue in the sky. Overall, therefore, we have warm colours in the sky and cold down on earth. This lower section is almost square in shape, cut across diagonally by a straight path, with a fence or railing running alongside it. The path is formed of a series of straight lines, individual strokes of the crayon, and the railing consists of three parallel bars. The lines of the path and the bars of the railing conform to a strict, if exaggerated, perspective, converging at a vanishing point on the horizon at the far left of the image. The depiction of the land and sea is all curves, contrasting with the rigid, linear depiction of the path – we are looking at geometric forms and abstract values, particularly contrasts: warm and cool colours, straight and curved lines, squares and triangles, horizontals and diagonals. These abstract values are given meaning by what is represented. The path is presumably a jetty, and we see the sea with a curving coastline forming a bay, and, judging by the greens interspersed on the right, some vegetation. There is an androgynous figure, just to the right of centre, cut off by the bottom of the image. Its mouth and eyes are wide open and its hands are clasped on either side of its face. Further away on the jetty two more figures – men, as they wear top hats and this is 1895 – are sketched out full length. There is a boat on the sea, and buildings on the land, just visible on the horizon.

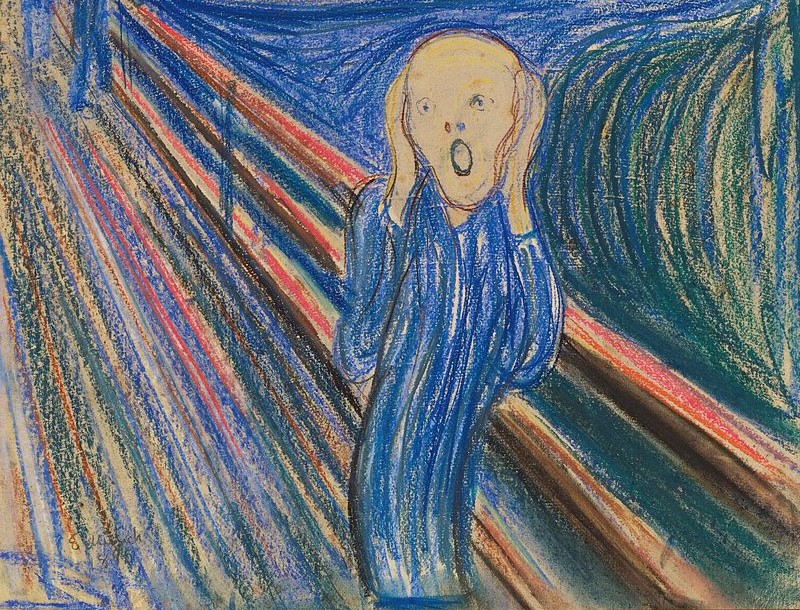

Looking closer at the figure at the bottom we can see its alarm more clearly, although the precise nature of the expression of this skull-like face is not easy to define. What is the wraith-like figure actually doing? The body seems almost immaterial: it is wavy, rather than solidly vertical, and is made of strokes more like the sky than the earth, all of which gives it a sense of insecurity. Is this person screaming, or does the open mouth speak of surprise, shock or horror? And do the hands express surprise as well, or are they clasped over the ears to shut out sound? There seems to be an unbearable pressure here, either coming from within, or closing in from the outside. As suggested above, the perspective of the jetty is distorted. It seems to recede too quickly, or, rather than receding, it could be seen as rushing towards us, giving the impression that we are zooming in, focussing on a close-up of the protagonist in a moment of high drama. Even the vegetation pushes in, the curved lines echoing the bend of the inflected wrist, pressing claustrophobically on the fragile figure.

Compared to the heightened drama of the protagonist, the two characters in the background seem relaxed, nonchalant even. One walks away, another stops to lean on the railing. If there is an audible sound – a scream – they do not seem to hear it: they certainly do not appear to be reacting to it. The boat just off the shore is a common feature in Munch’s work, and may imply the possibility of escape – but this is a possibility that is all too distant.

The sky is searing, with rich and brilliant colours, although oddly only the yellows are reflected in the water. The railing along the jetty, and even some of the planks of the path do take on some of the reds, but the intense colour is really the preserve of the sky, and is its defining feature. However, the nonchalance of the two figures could suggest that there is nothing unusual about it. Or maybe it is simply that they do not see it – or, that they do not see it like this. But then, the character in the foreground is not looking at the sky: he (is it ‘he’?) may have turned away.

I think that everything I have said so far is visible in the painting, although I can’t help wondering that so much of what I ‘see’ is coloured (deliberate choice of word) by what I have always known. It seems like ‘always’, anyway. I can’t remember when I first became aware of Edvard Munch, let alone The Scream. However, although there are unanswered questions in the interpretation of the image, we do know what Munch himself thought about the painting, as he wrote about it on more than one occasion. His first account was written a year before he made the first image. In a diary entry dated 22 January 1891, he said,

I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun went down – I felt a gust of melancholy – suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, tired to death – as the flaming skies hung like blood and sword over the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends went on – I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I felt a vast infinite scream through nature.

This makes considerable sense of the image: it is Munch and two friends. They have moved on, but he remains, ‘trembling with anxiety’. Maybe this explains the wavy forms of the torso, even if he is not now leaning against the railing. The sky is ‘bloody red’ and we get a sense of the ‘blue-black fjord and city’ even if the colour chosen is not quite as dark as that might imply. What is key here is the last phrase, ‘I felt a vast infinite scream through nature’. He is not screaming (it is ‘he’), but there is a scream, a scream that maybe he is trying to block out with his hands. However, this is problematic, as he doesn’t hear the scream, so he can’t silence it – he feels it. What is truly ground-breaking about this image is that it isn’t a picture of something seen, but of something felt. We are at the very beginnings of Expressionism.

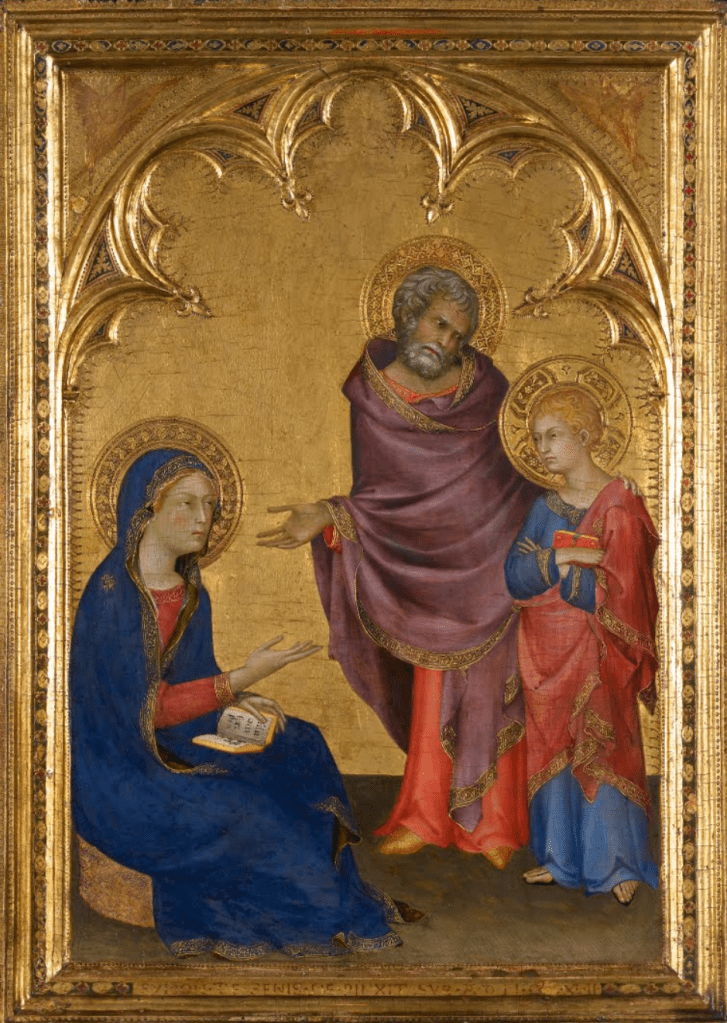

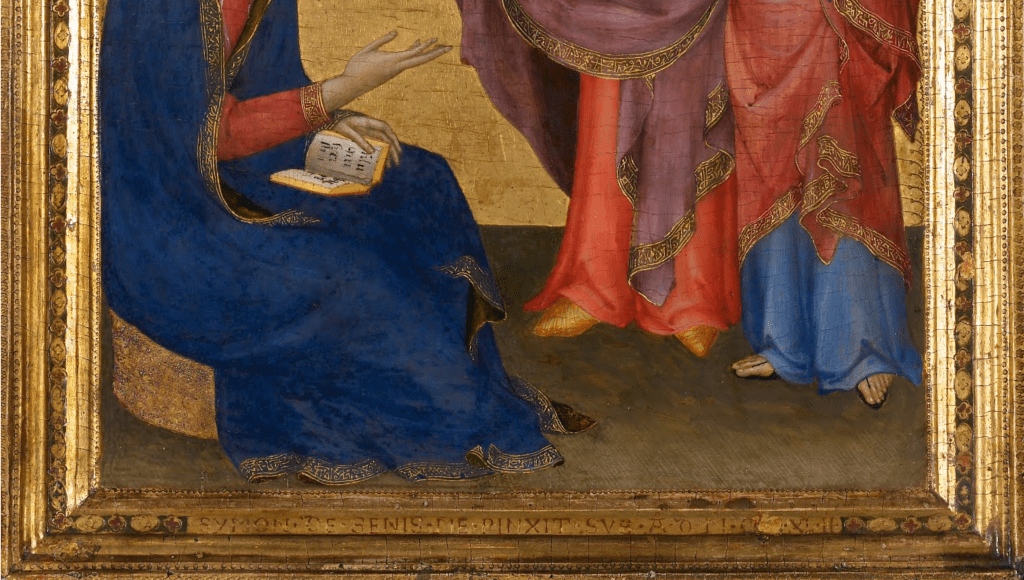

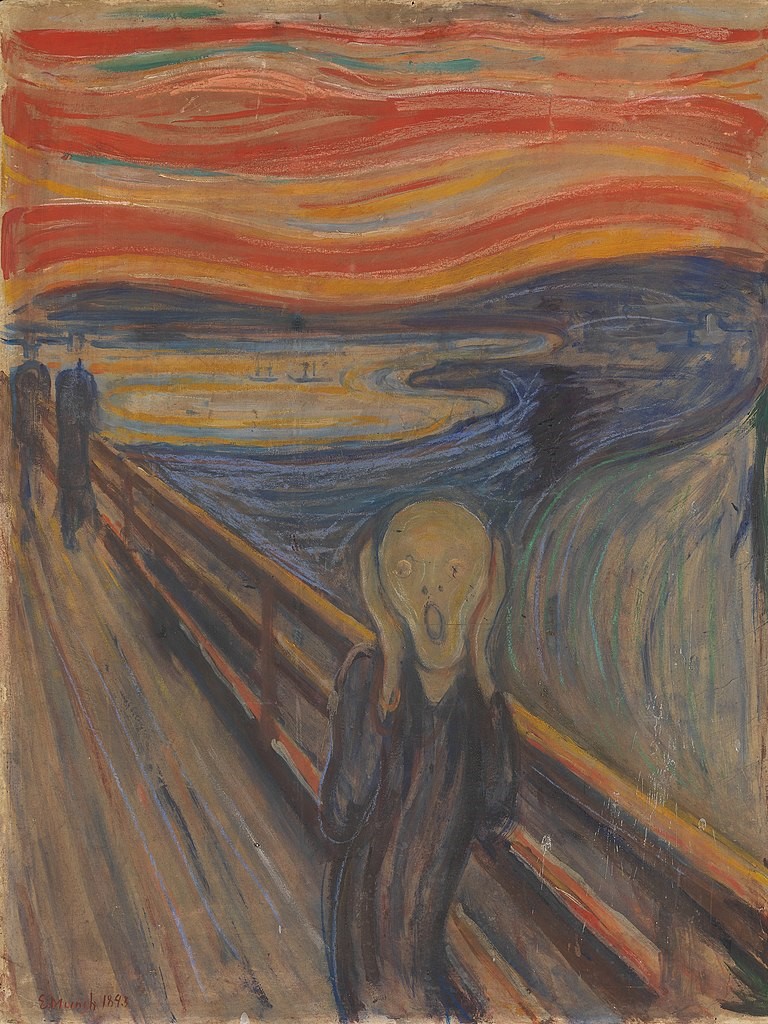

The year after Munch had this experience he tried to capture it visually twice, once in pastel – which may have been the first version, it’s not entirely clear – and once in paint, using both oil and tempera, with pastels as well. These two are both in Oslo, and are owned by the Munch Museum and the National Gallery respectively. The reason for thinking that the pastel is the earlier of the two is that, although the basic ideas are sketched out, the details are absent – no boats, and no buildings – features which do appear in what is, presumably, the later version.

There were two more versions in 1895 – the pastel which I have discussed (the only one in which one of the ‘friends’ leans on the railing), and a lithograph. We don’t know how many prints were drawn from the original stone, but about 30 survive, some of which were hand coloured by Munch himself. They were published in Berlin, and bear the title Geshrei, i.e. ‘The Scream’ in German, although the literal translation of this would be ‘Screaming’ or ‘Shouting’, apparently (‘The Scream’ would be Der Shrei in German, or, in Norwegian, Skrik). There is also a phrase at the bottom right, ‘Ich fühlte das grosse Geschrei durch die Natur‘ (‘I felt the great screaming through nature’). Often the image has been trimmed down, effectively cutting it out of the original ‘page’, meaning that the words do not appear – even if they were clearly important to Munch. This particular version, in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was signed by the artist in 1896.

A final version was painted in tempera in 1910. This, too, is in the Munch Museum in Oslo, and, like the others (with the exception of the lithographs), is on cardboard. The first version in paint (1893) is the one which bears an inscription. It says (in translation): ‘Could only have been painted by a madman!’ It is written in pencil on top of the paint, and recent analysis has confirmed that it is in Munch’s handwriting. It was probably his reaction – presumably ironic – to the public response to the painting when it was first exhibited in Norway in 1895. Typical of this was the comment of critic Henrik Grosch, who wrote that the painting was proof that you could not “consider Munch a serious man with a normal brain.” The implications of this statement would have been more profound for the artist than Grosch would have realised – probably. I don’t know how aware he was of Munch’s family background. Born in 1863, Edvard was the second of five children. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was five, as did his elder sister when he was fourteen. He was a sickly child, and was often kept out of school, which created an enduring sense of isolation. One of his younger sisters was diagnosed with a mental health disorder at an early age, and by the time The Scream was exhibited, she was cared for in a local institution. For the rest of his life the artist was haunted by the possibility that he had inherited the same condition.

Somehow, through all of this, he seems to have captured the essence of what could be described as one of the defining features of the 20th and 21st Centuries: angst. A quick internet search defines this as ‘a feeling of deep anxiety or dread, typically an unfocused one about the human condition or the state of the world in general’. The painting would have been perfectly at home in Vienna at the time of Sigmund Freud, but it also appears to visualise the Existentialists’ post-war fear of ‘the Void’: if there is no God, what is the point? For that matter, it could be an expression of man’s inhumanity to man, as seen in the holocaust, or even the cold war fear of nuclear annihilation. It speaks of the inner horror of so many of Francis Bacon’s subjects – even if it isn’t one of the usually acknowledged sources – and, oddly perhaps, it seems to demand to be owned. Both paintings have been stolen – the 1893 version in 1994, and the later one ten years later. And in 2012 the 1895 pastel – the one we have looked at – was sold for $119,922,600 to a private buyer. That’s very nearly 120 million dollars, which at the time was the most ever paid for a single painting.

‘Could only have been painted by a madman!’? It was as much the fear of the implications of this phrase – even before he had written it – that must have inspired his initial experience, and the images that flowed from it. This total honesty is what people have found hard to face, and yet, at the same time, it is so totally compelling. What else can have made it an early modernist Mona Lisa, ubiquitous and instantly understood? It undoubtedly touches a nerve, triggering an understanding of the human psyche. And, as we shall see on Monday, it was Munch’s psychological perception that helped to make him such a great portraitist.