Day 16 – Giulia Lama, Saturn devouring his Child, c. 1720-23, Private Collection (Sold at Christie’s, 2011).

Greetings from Venice! I’m here In Search of Giulia Lama, researching for my eponymous talk this Monday 10 June at 6pm. What better opportunity to revisit one of my early posts from lockdown 1: it dates from 3 April 2020 and was Picture Of The Day 16. As I remember it, lockdown started on Day 5 of the blog, and so today’s repost comes from the first two weeks of that remarkable time. It is the first talk in a summer dedicated to women – even if that’s not entirely clear from the title of the following talk, Velázquez in Liverpool, which will be on Monday 17 June. It will effectively be the fourth in my series A stroll around the Walker, and will celebrate the Liverpool gallery’s superb display of the National Gallery’s Rokeby Venus, one of twelve masterpieces which have been sent on holiday around the United Kingdom as part of the London-based collection’s 200th anniversary. It’s probably not immediately clear why this talk focuses on women as artists but, as I said last week, if you click on either link you can find an explanation: it’s a brilliantly clever and timely exhibition. There will be no talk the following Monday, but then on 1, 8 and 15 July I will take a proper look at Tate Britain’s vital Now You See Us, an exhibition of Women Artists in Britain, 1520-1920 (to quote the subtitle). If you click on either of those links, you can book for all three of the talks at a reduced rate. But if you are only free for one or two of them, I will explore the exhibition as follows: 1. Up to the Academy (16th-18th centuries, 1 July); 2. Victorian Splendour (the 19th century, 8 July); and 3. From photography to something more modern (looking at new media, and new means of expression, 15 July).

In addition to my Monday talks I will also be giving a talk at the Wallace Collection on Wednesday, 19 June at 1pm, entitled Getting carried away with Michelangelo and Ganymede. It is absolutely free and it would be lovely to see you there. You can either attend in person – in which case you just need to turn up on the day – or, if you’re not in or near London, you can watch online then, or over the next couple of weeks, in which case you’d have to book a (free) ticket for the Zoom webinar (and then, the recording) via the links. And finally (for now) if you missed my talk on Tate Modern’s Expressionists, I will be repeating it for ARTscapades at 6pm next Thursday, 13 June.

But for now, back to the remarkable Giulia Lama – the more I look at her, the more I learn, and the more I am enjoying her work. I have edited this post a little more than I would usually for various reasons, but am leaving the naïve wonder about our ignorance of the women who were practicing artists – so much has changed in the last four years! Apart from anything else, you will see that I repeat the received notion that women were encouraged to paint flowers. By the late 18th Century, many did, it is true (and there is a whole room in Now You See Us given over to the genre), but as far as I can see there is no evidence at all to suggest that this was common for women before then. There are a few notable exceptions from later in the 17th Century, of course (e.g. Rachel Ruysch) but it was by no means prevalent, and the field was still dominated by men. Nevertheless, this is what I said back in 2020:

Why do we talk about women artists so rarely? Apparently it wasn’t always the case. According to Grizelda Pollock, one of the earliest and most authoritative feminist art historians, they were regularly included in dictionaries of art and artists until the beginning of the 20th Century, at which point they were all but written out. This year [2020], with Artemisia at the National Gallery [which was postponed, but then had to close early anyway, both thanks to the pandemic] and Angelica at the Royal Academy [which, for the same reason, had to wait until 2024], let’s hope they are being written back in, and not just as token representatives, but as vital and inventive artists.

The fact is, there always were fewer women who could make a career in the arts – they were not given the training. It helped if their father was an artist, as in the case of Angelica Kauffman (#POTD 14), especially if his studio was very busy – or he didn’t have any sons to help him. But they couldn’t get apprenticeships with another artist, as that would mean living with a man who was not a member of the family, and at the age of 11 or 12 – or any age, quite frankly, for a woman – that was simply not appropriate. When academies were founded, starting in the second half of the 16th Century, women weren’t admitted, because women didn’t get an education anyway. The few women who did succeed usually had unusual fathers – i.e. fathers who were artists (as above), or who believed that their daughters should be educated. Another possibility was that the girls were initially ‘amateurs’, practicing the usual accomplishments any young lady should have – music, and some ability with a little delicate decoration – until they turned out to be outstandingly good at it and so broke through to the ‘mainstream’ [you could argue that this was the case with Sofonisba Anguissola].

In any case, it was thought that women lacked the necessary intellect to understand something like perspective and didn’t have the necessary education to know about classical mythology, so they would never be able to paint great narratives. Women weren’t supposed to paint portraits of men, in case the men assaulted them, and landscapes weren’t a great idea because, out in the countryside, they might be attacked by brigands. So they were left with Still Life, because, on the whole, a still life won’t bite back. The most distasteful thought was that they might attend a life class. Drawing and painting the male nude became the foundation of artistic training, because without a thorough understanding of male anatomy – or at least surface anatomy – an artist would never be able to paint a battle scene, or a martyrdom, those uplifting stories which were the apogee of art. It would be so inappropriate for a woman to look at a naked man, let alone draw him. Ladies were supposed to avert their gaze, and not stare at anything.

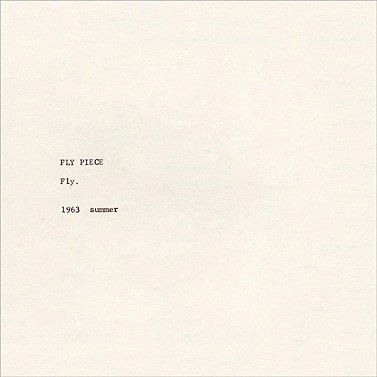

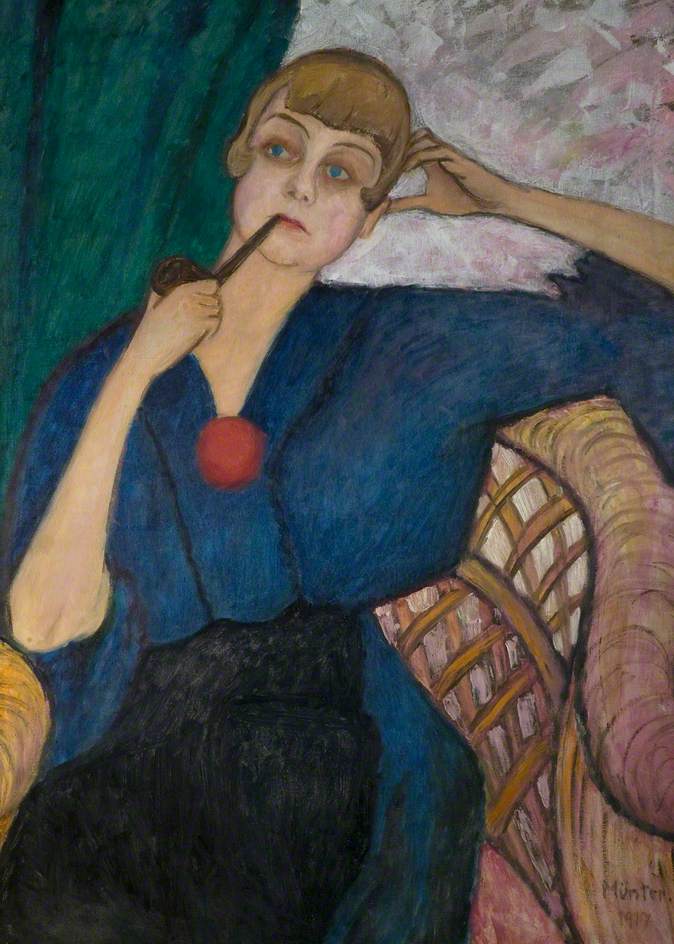

So, that’s what we’re left with – pretty flowers, ladies having tea (#POTD 15), or the artist herself indecisive between painting and music (#POTD 14). I have yet to cover the pretty flowers [but would eventually: see 126 – Mary Moser]. It’s all pretty girly really, lets face it. Just like today’s painting…

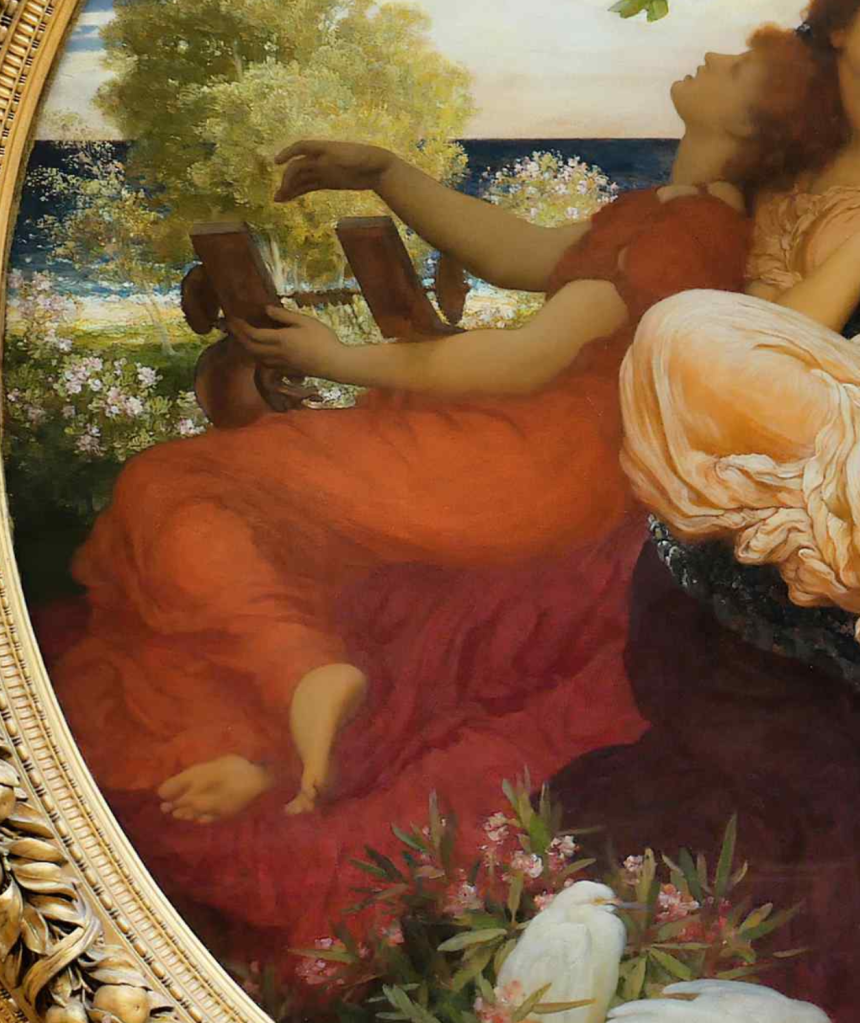

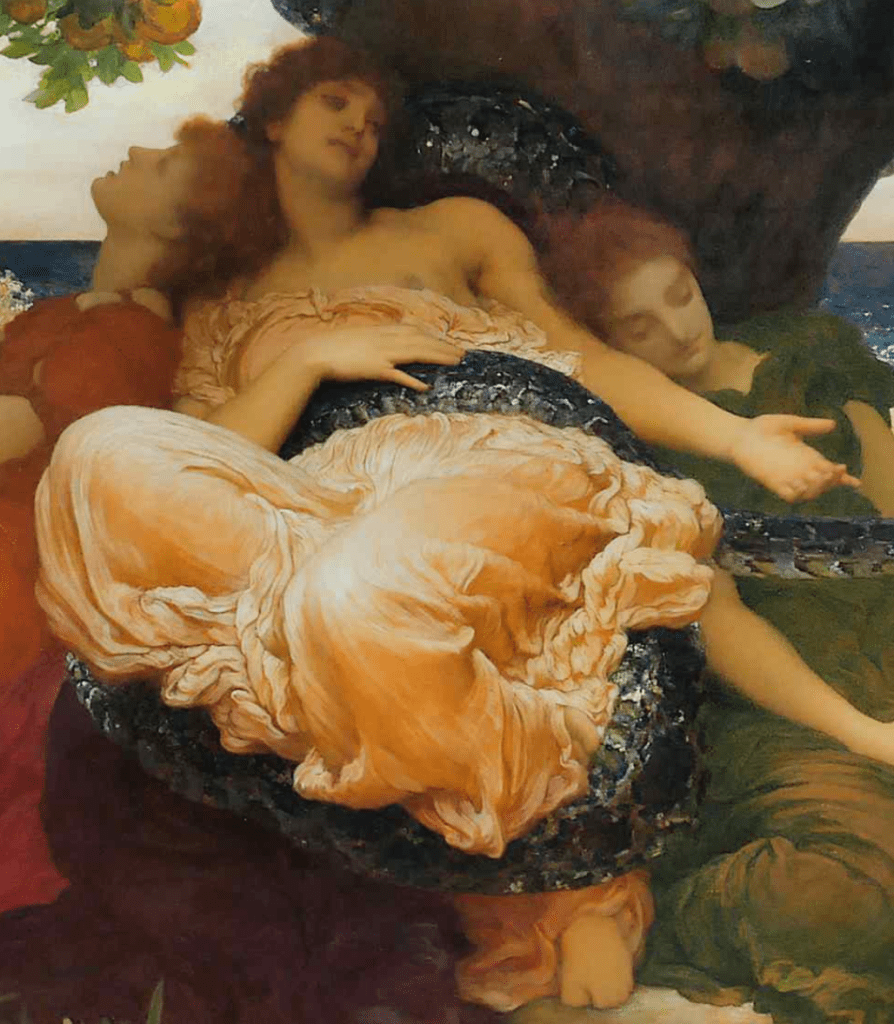

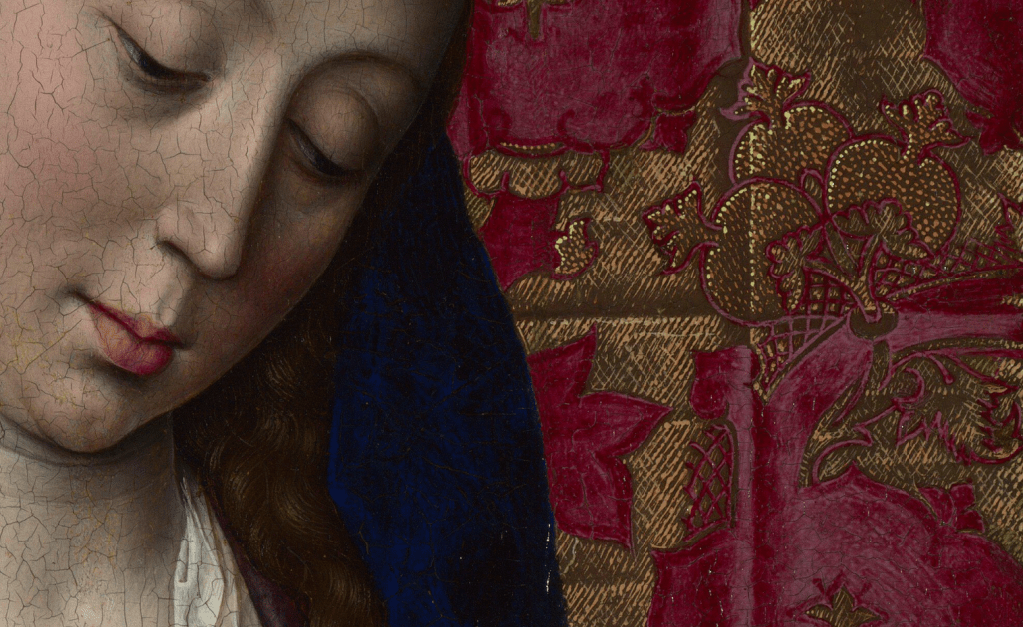

Sadly we don’t know a huge amount about this image, and the attribution to Giulia Lama isn’t universally accepted. However, I think few people doubt it now, particularly as her painting is getting better known. We also know relatively little about Giulia Lama herself. She was born in the Parish of Santa Maria Formosa in Venice, the daughter of an artist (it helps). One of her great works is in the church there, a Madonna and Child with Saints on an impressively grand scale [I saw it again yesterday, and will talk about it on Monday]. Her style is remarkably close to that of one the greatest but underrated artists of 18th Century Venice, Giambattista Piazzetta, whose works are the smoky colour of bitter toffee apples, if such a thing exists. His fame was eclipsed by that of Tiepolo, whose candyfloss colours are ideally suited to those of a sweet tooth – I love them both.

Why was Lama’s style so similar to Piazzetta’s? At this point a discussion arises: was Lama a student of Piazzetta’s, or a colleague? Opinion is tending towards the latter: she was undoubtedly trained first by her father, and then may well have continued her studies alongside Piazzetta in the school run by artist Antonio Molinari – which could make her the first woman to attend any sort of art school.

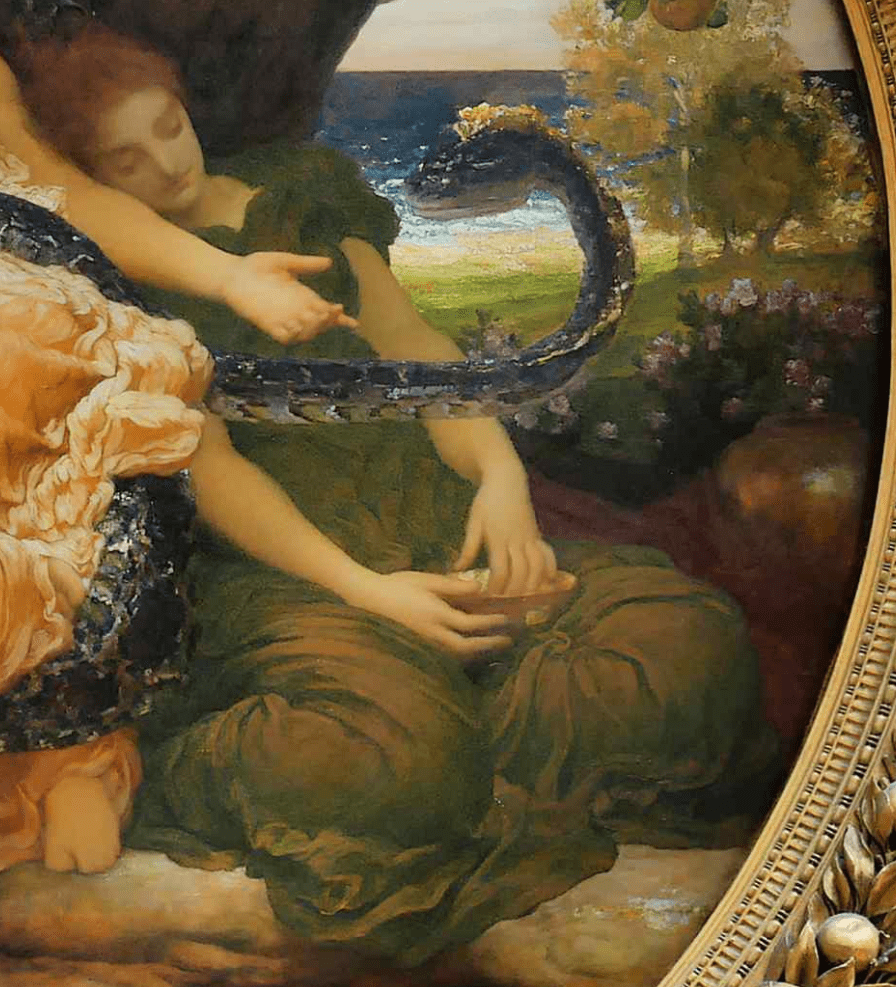

Today’s painting could almost be a manifesto overthrowing all the reasons why women couldn’t become artists. It’s a classical story, shows a male nude, and has fantastic foreshortening (basically perspective applied to a single object). And it is anything but ladylike – or, for that matter, for a classical narrative, anything but uplifting. It’s a man eating his own child! It is also a story that proves that we don’t learn from history. Saturn made it to the position of Top God after his mother, Gaia (the Earth), got understandably upset because his father (Ouranos, the air) kept imprisoning their children. Eventually she’d had enough, and so gave Saturn (her son – also known as Chronos) a very sharp knife, and encouraged him to castrate his own father (Ouranos), which he did. The severed genitalia fell into the sea, which was therefore made fertile, and the result was Aphrodite – her name means ‘born from the foam’. The Romans called her Venus, or course. This story helps to explain her appearance in Botticelli’s famous painting (#POTD 8) – but in the process stops it looking quite so charming.

Knowing how easily a god could be overthrown, Saturn didn’t want to take risks, and so ate each of his own offspring as they were born. Eventually his consort, Ops (Rhea, to the Greeks), lost patience with this, and handed him a stone, pretending it was the latest baby. The new-born was smuggled to Crete, where it grew up to be Jupiter. As an adult, Jupiter returned, forced Saturn to regurgitate his siblings, and they all got together and overthrew Dad. And you thought Eastenders was bad.

Precisely why Lama chose to paint this subject – or who commissioned her to do so, and why – we may never know. A contemporary account says that many churches wanted her to paint them an altarpiece, so highly was she respected. As well as the one I’ve mentioned in Santa Maria Formosa there is another in San Vidal, just over the Academia Bridge [which will also feature on Monday]. But that doesn’t explain this painting. Maybe she painted it simply because she could. She certainly seems to have been the first female artist to have studied the male nude – and she did so often: I’ve included two of her drawings below, and they are superb. She uses black and white chalk in one and red and white in the other, the light and shade giving the body a sculptural feel, with short, stabbing strokes of the chalk, over broader areas of shading. They show a remarkable ability to articulate the limbs and arrange the body in complex ways, but with the slight exaggeration that creates movement and drama, the essence of all great Baroque art.

The same qualities can be seen in the painting, the limbs of Saturn creating diagonals across the surface, and into the depth of the painting – the power of this foreshortening is unimaginable without the awkward and contorted postures seen in her life drawings.

The legs continue the shallow diagonal of Saturn’s grasping left forearm, while the body of the child, softer, lighter and therefore more succulent than that of his swarthy father, is parallel to the muscular upper arm. It marks the diagonal from bottom right to top left, whilst also creating depth for the composition. All this is set in bright sunlight, making the figures stand out clearly from the dark rock in the background, and creating the deep dark shadows that define Saturn’s muscularity. It’s not pretty, and it really isn’t ladylike. In many ways, it isn’t even very nice. But it is brilliant – an astonishing bit of painting and a fantastic work of art.