Johann Zoffany, The Academicians of the Royal Academy, 1771-72. Royal Collection Trust.

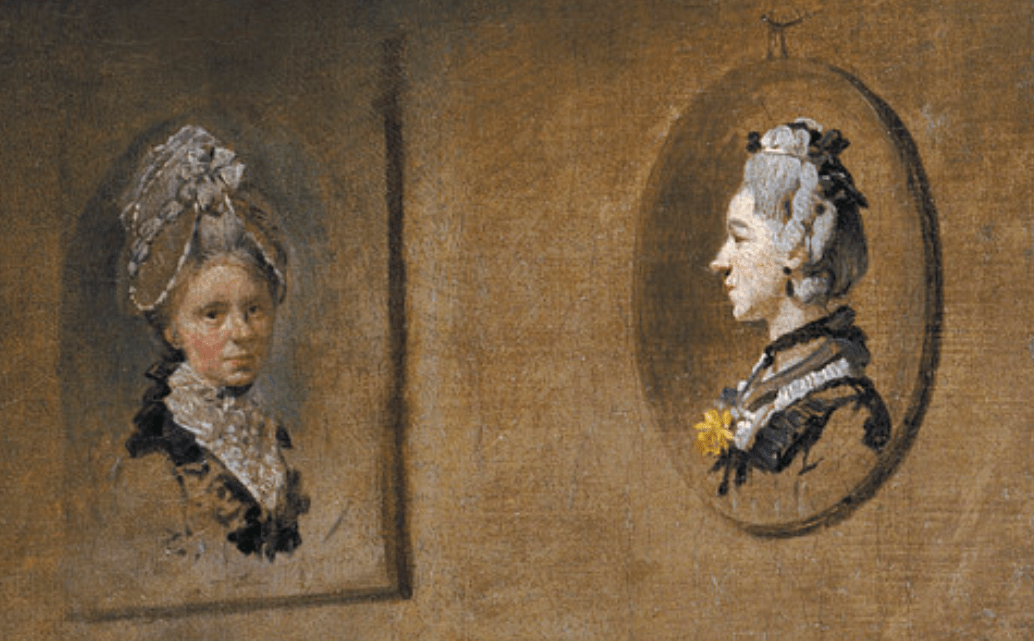

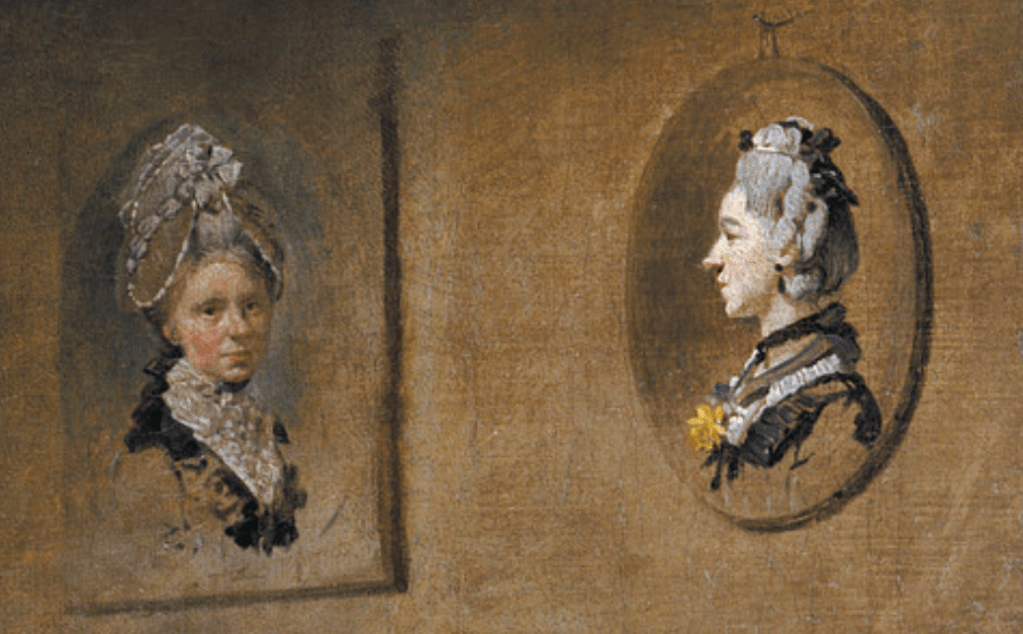

Two weeks ago I talked about Mary Moser, one of the two women who, in 1768, were founder members of the Royal Academy. Today I would like to talk about a portrait of her, which hangs next to another, which depicts her fellow founder Angelica Kauffman (who will be the last of my Three Women in the 18th Century this Monday (10 May) at 2pm and 6pm). They are not ‘real’ portraits, but details from a larger painting by Johann Zoffany, which is the nominal subject of this post. Angelica Kauffman is on the left – the rectangular canvas – with Mary Moser on the right, in an oval. The two still life paintings I discussed before (126 – Mary Moser) were also oval: I wonder if that is why the same format is used here? She was, as you may remember, famed for her flower paintings, which certainly explains why she has a large, yellow bloom attached to her bodice in Zoffany’s imagined portrait. In both, the bust-length image appears against a plain background. It might have become more elaborate: neither portrait has been completed. Today we are dealing with unfinished business.

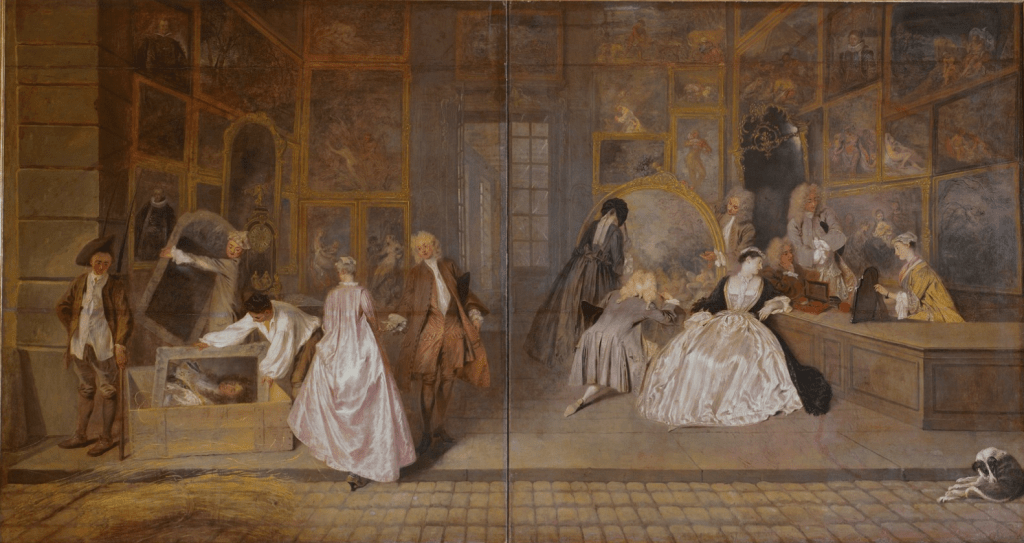

Despite the fact that both paintings are ‘works in progress’, we can see that the two women are fashionably dressed, and elaborately coiffed. If I knew more about the history of hair I would probably go into raptures about the complexities of the crimping, curling, combing and powdering, and of the ribbons and bows with which they are bedecked, but I don’t – so just look for yourselves. Their barnets alone are a work of art (from Barnet Fair – hair), and could be a credit to one of the greater sculptors of the newly founded Royal Academy of Art, which is where they are supposed to be. For years it was assumed that what follows is a depiction of the Life-drawing Room in the first home of the Academy, Somerset House (now the home of the Courtauld Institute), but it is, in all probability, the invention of the artist, who was simply imagining a space suitable for such an august gathering.

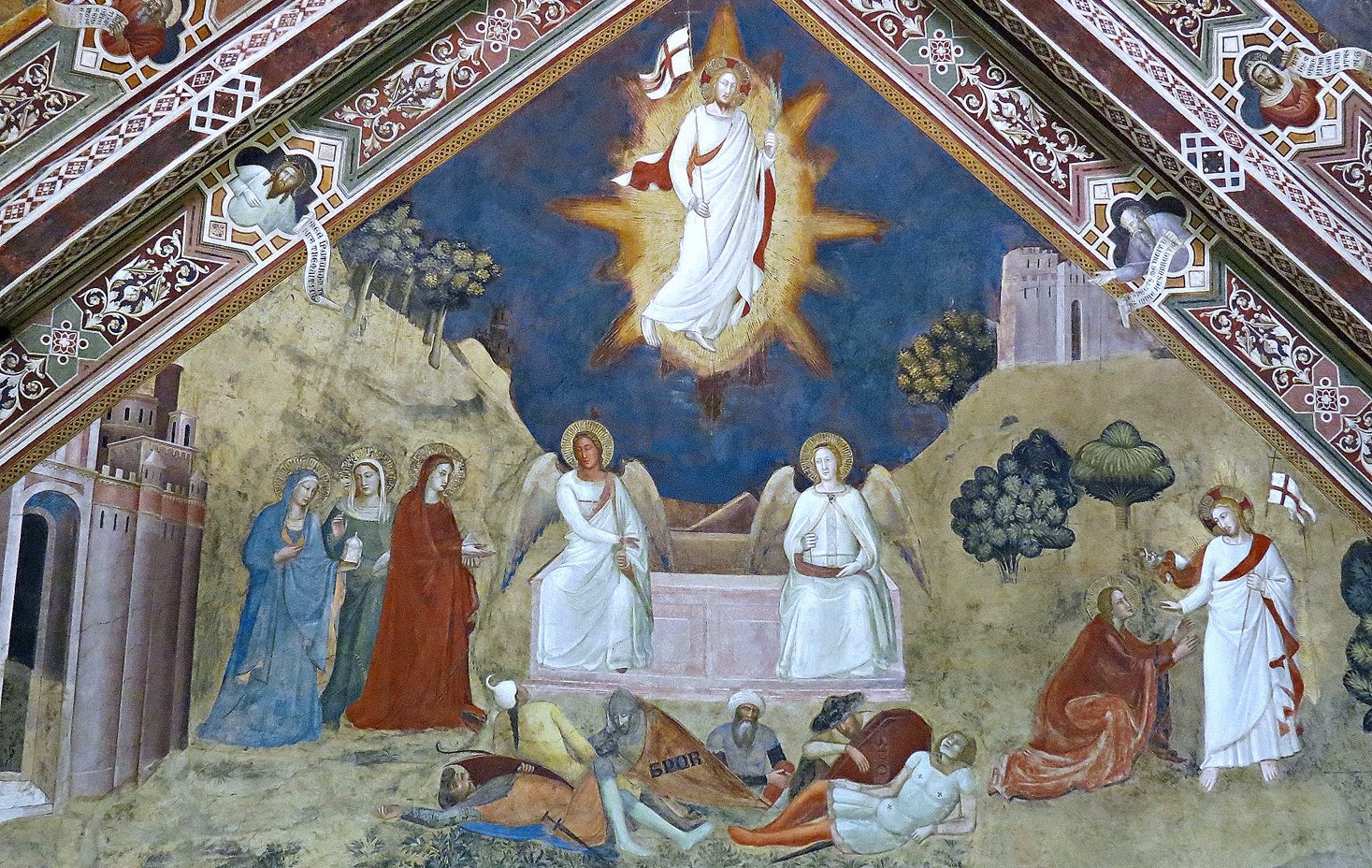

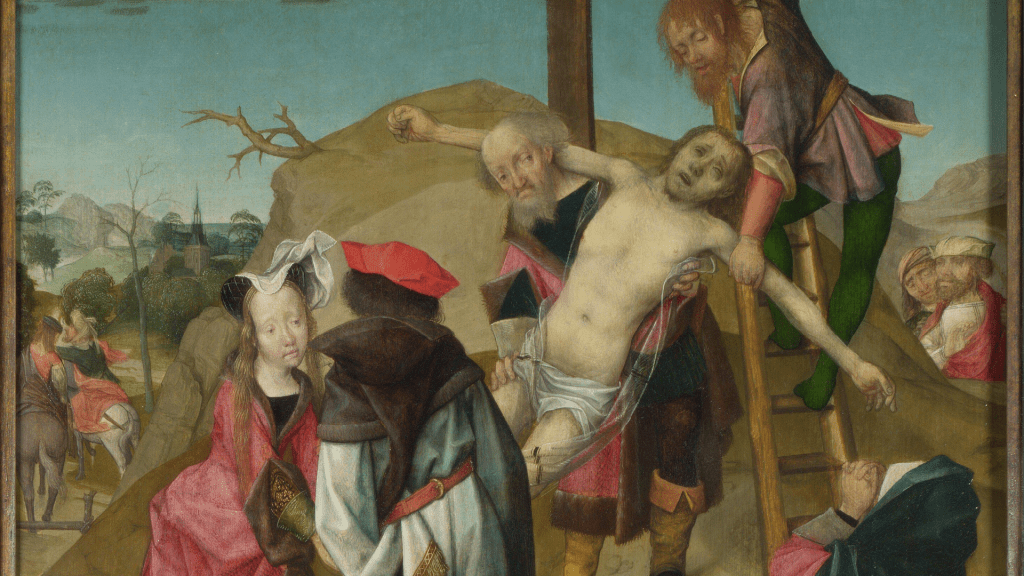

Founded by George III in 1768, the Royal Academy of Art was the first British art school to receive the royal seal of approval. The idea was to promote the arts, and to train artists to be worthy of its status. Rather than just portraits of the great and the good, and of their land (i.e. landscapes), several of the Academicians, and especially its first President, Sir Joshua Reynolds, wanted British Art to aspire to the heights achieved by that of other nations. To realise their ambitions, not only should artists show an awareness of the work of others but they should also paint the highest category of painting – ‘History’. This was a narrative work, which could be based on history (usually classical), but which was more often inspired by myth (always classical), the bible, or the lives of the saints. And if what was commissioned didn’t match up to these exalted standards, the artists would just have to make sure that it did. Reynolds often based his portraits on the works of others, dressing sitters like mythological heroes, or theological virtues, for example. Zoffany does something similar here, basing the composition of his group portrait on one of the greatest works by one of the most famous renaissance artists.

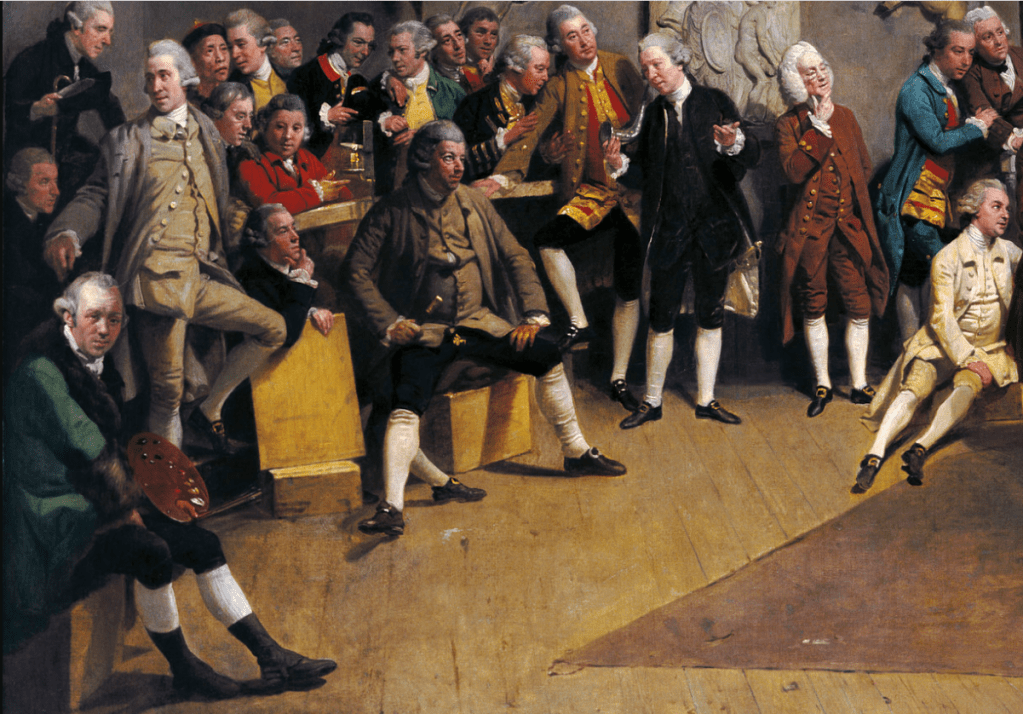

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509-11) in the Vatican Palace shows the major philosophers of the ancient world gathered together in one space, with Plato and Aristotle at the very centre, framed by the distant arch, wearing red and blue cloaks respectively. The other thinkers are arranged in a broad arc, a c-shape traced out on the floor, or a circle left open at the front to encourage us to look in. The image is flanked by two enormous sculptures of Apollo and Minerva, both inspirers of the arts, at top left and right, with smaller, square reliefs below. Zoffany likewise arranges his academicians in an arc, although he doesn’t pull them so tightly together in the foreground. Almost all of the founder members are here, the most notable absence being Thomas Gainsborough. Zoffany also displays a number of casts of classical and renaissance sculptures on shelves and hanging from the walls at the back. In addition, there is an écorché figure – a sculpture of the human body with the skin removed to show the muscle structure – in the back right corner of the room: it stands against the wall with one arm raised.

Whereas for Raphael the incomplete building (not unlike the ‘new’ St Peter’s, under construction at the time) allows daylight to flood in, for Zoffany there is a single chandelier – or rather, a multiple oil lamp – hanging from the ceiling. Using a single light source like this serves to illuminate the models who are preparing for the life drawing class, while also casting deep shadows on the other side, thus enhancing their sculptural forms.

At the centre, in the place of Plato and Aristotle, on either side of a rectangular relief not unlike those in The School of Athens, are Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Academy, and William Hunter, who was not actually an artist. He was physician to Queen Charlotte, and served as the professor of anatomy at the Academy from 1678-82. He is also connected to the history of art through his own personal collection – which was, admittedly, mainly in the field of Natural Sciences – which he eventually bequeathed to the University of Glasgow where he had studied (he was born in East Kilbride, just 8 or 9 miles away). This collection forms the nucleus of the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery.

Reynolds wears sober black and ostentatiously lifts his ear trumpet. He had spent two years in Rome in the middle of the century, and while there suffered from a severe cold, which left him partially deaf. Nevertheless, the more cynical suspected him of using the trumpet to draw attention to himself. I can only hope that Zoffany chose Reynolds and Hunter deliberately to stand in for Plato and Aristotle. Quite apart from the fact that they were the ‘leading lights’ of the Academy, Reynolds was always seeking out the ideal, and dressing his portraits in the guise of an unseen image which existed elsewhere, while Hunter, as an anatomist, was totally involved in the evidence before his eyes. This is the implication of the gestures that Raphael gives the ancients: Plato points up to a higher plane, while Aristotle’s level hand gestures to what we see down here on Earth.

Johann Zoffany, the German-born artist who, after ten years in Rome, arrived in England in 1760 at the age of 27, shows himself in the left foreground, palette in hand, looking out towards us. In some ways he takes the place of Pythagoras, kneeling, tablet in hand, in the left foreground of The School of Athens. Just above him, his left knee raised, while he simultaneously looks over his right shoulder, is Benjamin West, who would become the second President of the Royal Academy (we saw him ‘enthroned’ in the centre of Henry Singleton’s painting two weeks ago). He is leaning against a curving desk, which arcs around the back of the room, and which would have been used by the students when they came to draw. His complex pose is ultimately derived from the Michelangelesque exaggeration of contrapposto which Raphael gives to the philosopher sometimes identified as Parmenides, thought by some to be a ‘hidden’ portrait of Leonardo da Vinci as well. Behind West – with his head just to the right of West’s wig – is Tan-Che-Qua, a Cantonese sculptor who just happened to be in London when Zoffany was painting, and whose image was not to be missed.

On the other side of Zoffany’s work we can see what is taking up most people’s attention: two naked – or nearly naked – men. A life drawing class is being set up, even if precious few of the Academicians seem prepared to participate. Sitting with his legs extended on the left of this detail, Charles Catton the Elder, a painter (no, I hadn’t heard of him either) echoes Diogenes, sprawled across the floor to the right of centre in The School of Athens. The academicians all look towards the model raising his right arm while someone hooks it into a sling – so that the model can keep his arm up for the duration of the drawing exercise. That ‘someone’ just happens to be George Michael Moser, father of Mary – although I’m afraid to say I have beheaded him in this detail. The model who is ‘next up’ is sitting a little closer, and looks out towards us as he takes off his left stocking. His shoes and clothes lie abandoned on the floor next to him. Holding one ankle as it rests on the opposite knee, he adopts the pose of the Spinario, a classical Roman bronze of a boy taking a thorn from his foot.

The painting tells us everything that the Royal Academy thought that a good artistic training – in whatever discipline – should include: a knowledge of the classical past – seen in the plaster casts, and embodied in the pose of the Spinario; a knowledge of the works of the Old Masters (not only is the composition based on The School of Athens, but the figure standing on one leg in the centre of the back wall is a version of the Mercury by Giambologna); the use of sculptures to draw from, as a starting point – suggested first by Alberti in On Painting, written in the 1430s; a good knowledge of human anatomy, expressed through the presence of William Hunter, and of the écorché figure in the back corner; and, ultimately, life drawing. Without an understanding of the male physique, gained by careful observation, how could any promising artist master History painting, and its depictions of the righteous battles and noble acts of mythological and Christian heroes? But if life drawing was essential to become a great artist, what chance did women stand? How appropriate would it be for a woman to be present while such an exercise was takiing place? While it may have been acceptable for men to draw naked women, the women in question were usually little better than prostitutes, or actresses. But for a respectable woman to behold a naked man? Clearly this was not on. The attitude that this apparent regard for female decorum represents is embodied, I think, in the action of miniaturist Richard Cosway, who stands in the right foreground, proudly erect, his gaze directed firmly over his right shoulder and his right arm extended, with the hand resting on his walking stick… which is firmly planted on the truncated and supine bust of a classical female nude. Am I mistaken in seeing this as profoundly disrespectful?

The women are side-lined. They cannot be present at the life drawing class, so they cannot become great artists, and Zoffany can only include Kauffman and Moser as portraits, hanging on the wall. They become, as women had always been, the subjects of art, rather than the creative people who make it. And not only that – they are unfinished, incomplete. They owed their position as founder members of the Academy to their brilliance as artists, but their connections undoubtedly helped. Moser’s father was, as we have seen, also a founder member. Angelica Kauffman was a personal friend of Sir Joshua Reynolds. But their admission was, like these portraits, unfinished business: after them, no other woman was admitted until Dame Laura Knight became an Academician in 1936. She was the first woman to be elected, and that wasn’t until 168 years after the Academy had been founded.

You could argue, of course, that Zoffany didn’t have a choice. If he wanted to paint a life drawing class – which would not only show off his skill, but also demonstrate everything in which the Academy believed – it really wouldn’t have been right, at the time, for a woman to be present. However, the fact that Henry Singleton included both of these women in his group portrait The Royal Academicians in General Assembly – a meeting they did not, in reality, attend – shows that it might have been possible for them to be included in person (although admittedly nobody at the Assembly was naked). But Singleton also depicted their paintings, which speaks of a great degree of respect for the women and for their work. As it happens, the ceiling paintings by Angelica Kauffman – which are visible in their original location in Singleton’s group portrait – have just this week been reinstalled in the ceiling of the Front Hall of Burlington House, the RA’s current home. I will include all four of them this Monday as part of my discussion of Angelica Kauffman: Academician at 2pm and 6pm.

These two women may have been marginalised by Zoffany, and made subjects rather than makers, but maybe that wasn’t his fault. Now, however, the tables have turned. Of all the founder members depicted by Zoffany, they are among the few whose names are becoming better known, and certainly the two in whom people are now more interested. Kauffman in particular embodied the ideals of the Royal Academy more than many others, and in the process created some truly glorious History paintings: she was one of the most famous artists of her day. I look forward to talking to about her on Monday.