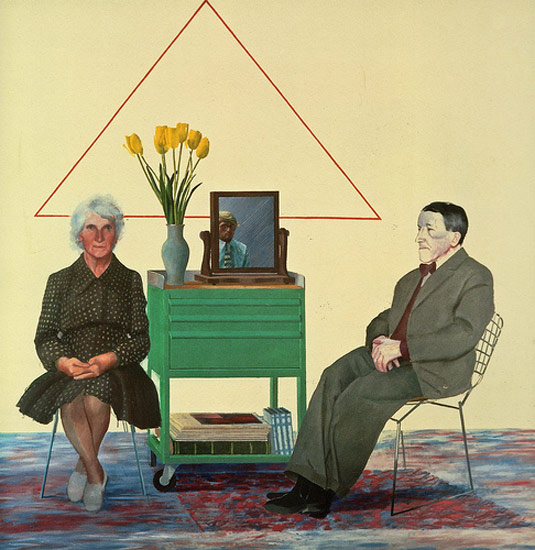

Unknown artists, The Palmers’ Window, mid-15th century. St Lawrence’s Church, Ludlow.

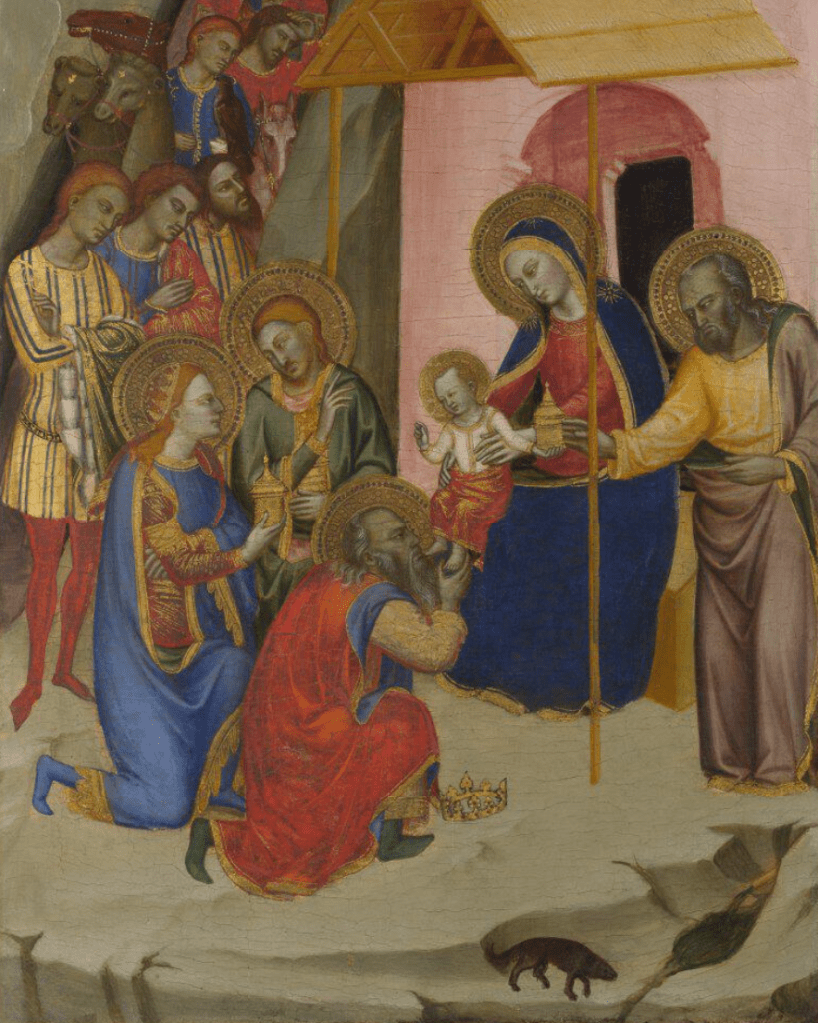

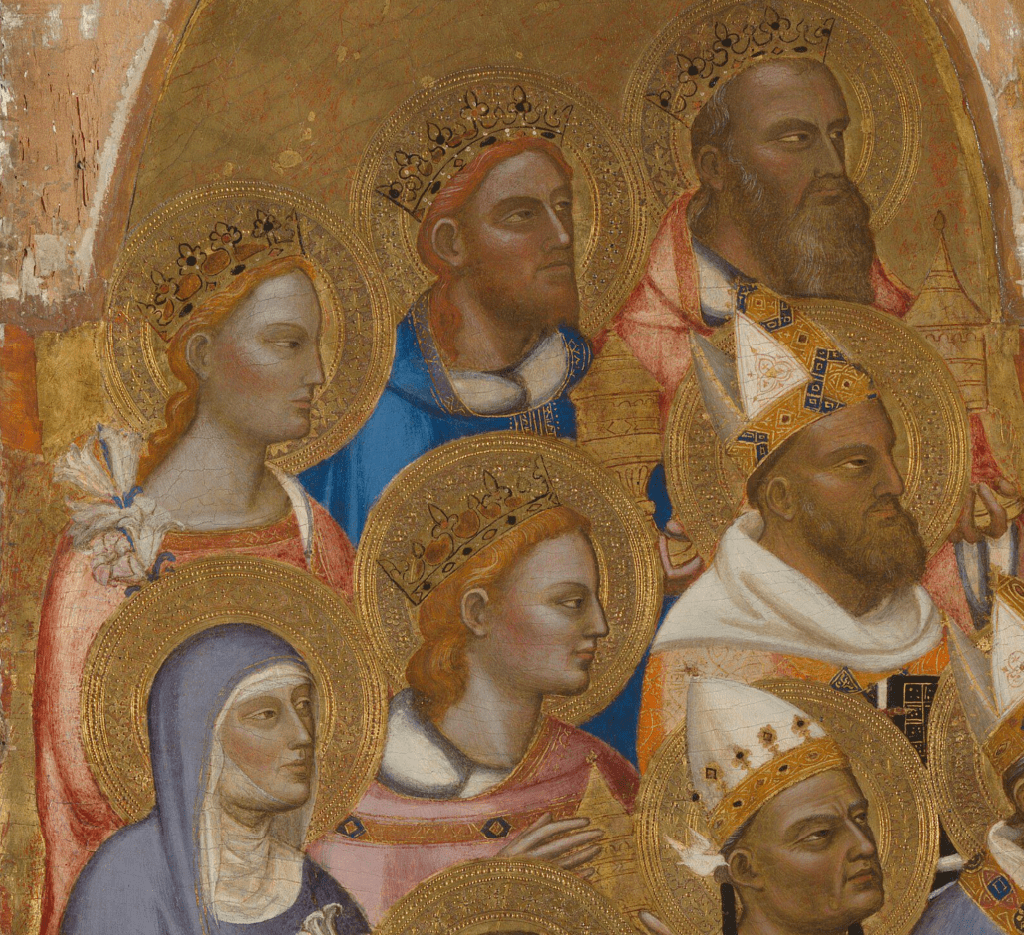

In the three and a half years I’ve been writing this blog I have only talked about stained glass once (see Day 78 – St Petroc). However, given that this Monday, 16 September at 6pm I will be talking about some English saints, and that much of the art which depicted them has been destroyed, this is an ideal opportunity to look at some more. The saints I am interested in are Behind the King in the National Gallery’s splendid Wilton Diptych, and they are the subject of the second of my two talks wondering Who’s Who in Heaven? This week, as well as identifying the characters themselves, we will also think about why it is useful to know who they are: what does the choice of saints tell us about the patron, the original location of the painting, and the reasons why it was painted, for example? Two weeks later (30 September) we will set out on The Piero Trail, and after two more (14 October) we will head back to the National Gallery to rediscover Van Gogh in the National Gallery’s brilliantly reviewed exhibition, hoping that this is Vincent, speaking for himself… The details, and links to book, are also in the diary, of course.

There are many different ways of organizing a stained glass window, even more than the variations on the possibilities of an altarpiece, I suspect. It is quite common to have a whole series of individual saints in different lights (the section of a window which forms a single opening contained by the stone tracery), but it is also quite common to have a number of different, unrelated narrative scenes. In this case each light has a single episode from a longer story, like chapters in a book – or maybe paragraphs, as each episode is relatively short. Actually, it is two stories combined into one, but that turns out to be the whole point of the window. It hasn’t always looked like this, though, even if it probably did when it was first made in the middle of the 15th century. It was lucky to avoid the wide-spread bouts of iconoclasm that happened as a result of the reformation, both during the reign of King Edward VI, England’s first truly Protestant monarch, and the interregnum, with the Commonwealth headed by that notable killjoy Oliver Cromwell. The iconoclasts were sent far and wide to destroy what was considered to be idolatrous imagery, but they didn’t get everywhere. The majority of the glass in St Laurence’s Church in Ludlow survived, and it’s a real treasure trove. Glass survived more than sculptures and panel paintings as it happens, partly because it was harder to reach, and also for purely practical reasons: the iconoclasts didn’t necessarily want the churches to get cold or wet. However, it wasn’t just the iconoclasts who got to the windows. Churches were frequently rebuilt and redecorated for reasons of taste, or as the result of decay. By the 19th century several panels from this particular window had been moved, and were installed in the tracery of another, nearby window. By then, though, there was a considerable revival in the Church of England, and various waves of restoration ensued. This didn’t always return the material to its original state (often that just wasn’t possible), but to what the 19th century artists and designers thought that it should have looked like had the original makers done it properly. And if they didn’t know what that was – well, they just made it up. We shall see some evidence of that here… although thankfully, it seems, not too much. We will read the window as you should read any good book – in a European language, at least – from left to right and from top to bottom. For some of what follows, I’m indebted, among other things, to an agreeably thorough study by Professor Christian Liddy of Durham University in the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society, as well as to some superb photographs by @granpic on Flickr.

At the very top there are two coats of arms. On the left we can see a golden cross against a blue background (my apologies to anyone interested in heraldry, but I’m going to use the standard English terminology for colours, so that I and everyone else can understand). In each of the four corners of the cross, and underneath it, there is a golden bird with no legs, described as a martlet. These are attributed arms, which means they were effectively ‘invented’, a practice applied to members of the nobility who had lived before the age of heraldry. In this case they were the attributed arms of a king of England who was later canonized: Saint Edward the Confessor. His title implies that he lived a life of great sanctity, but rather than dying for his faith (which would have made him St Edward Martyr), he died in old age still confessing his faith. Historians might argue this fact about the man himself, but that is all but irrelevant to the beliefs of those who commissioned the window. Recently I realised that the same arms appear on the roof of Aberdeen Cathedral, where they are attributed to St Margaret, mother of King David I of Scotland. The arms to the right are those of the town itself, Ludlow, not far from the border between England and Wales. However, they might not be original: when the window was restored/reconstructed between 1875 and 1878 the firm responsible asked for confirmation of the appearance of the Ludlow Arms. This could suggest that originally the space was given over to something else, maybe the arms of the Palmers’ Guild, the patrons of the window. As we shall see, they claimed that their statutes had been authorised by none other than St Edward the Confessor, but that’s not possible: the guild wasn’t instituted until the 13th century, and he famously died in 1066.

Palmers were theoretically people who had travelled to the Holy Land, and come back with a palm leaf as evidence: to all extents and purposes the word ‘palmer’ was synonymous with ‘pilgrim’. I first came across it – as with so many great words – in the works of William Shakespeare. Romeo and Juliet can be quite tricky for the protagonists as we have to believe that they are truly and profoundly – and instantly – in love, and yet they are hardly ever on stage together. You’ll have to take my word for it: I played Romeo early in my career, and there are few lines to convey such intensity. But of course, as ever, Shakespeare helps you. The first words that the two lovers speak to each other form a perfect sonnet: fourteen lines, perfectly scanned, with an elegant rhyming structure to boot. If their ability to improvise one of the tightest verse structures as teenagers in the middle of a party to which one of them was definitely not invited is not a sign that they were made for each other, I don’t know what is. It’s Act 1, scene 5 and these are their very first shared words:

ROMEO

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

JULIET

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.

ROMEO

Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too?

JULIET

Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.

ROMEO

O then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do.

They pray: grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.

JULIET

Saints do not move, though grant for prayers’ sake.

ROMEO

Then move not while my prayer’s effect I take.

I rest my case. A bit of digression, I know, but… palmers are pilgrims.

So far we know that the window is in Ludlow, and dedicated to St Edward the Confessor. In the lights below the arms (see above) there are six blue arcs, framed by small sections of red and green glass, containing a series of blue circles. I’m sorry, but I’ve never seen anything like this before (I’m not actually a Window Historian), and can’t begin to explain the origins of this decoration. Maybe something to do with the vault of Heaven over the ensuing story which happens down on earth, but I couldn’t even tell you whether they are original to the 15th century design, or a 19th century invention.

This is the upper tier of lights. At the top of each is a canopy, and the way they are designed helps to date the window to the mid-15th century, ‘three-sided structures decorated with turrets and pinnacles, with arches opening to reveal a vaulted roof’, according to Christian Liddy. The chapel containing the window was rebuilt between 1433 and 1471, which adds strength to the suggested date. In the left light we can see an English ship (the flag of St George is flying on the main mast), on which we can see a man in green and two in blue. The next two lights show more men in blue in the countryside, while yet more are gathered, in an interior setting, in the fourth light. It’ll be easier to understand with details. The majority of the story actually comes from the Golden Legend, which I have mentioned often, a collection of stories about the lives of the saints put together in the 1260s by a Dominican friar (who eventually became Bishop of Genoa) Jacobo da Voragine. However, the Life of St Edward the Confessor wasn’t included in the original version: it was one of several Lives of English saints which were added to an English translation of 1438. The so-called the Gilte Legend was probably the source for the Palmers’ Guild window, even if the story was also included in a subsequent translation which became far better known: the version by William Caxton. However, as that wasn’t published until 1483 it was too late for this window.

The man in green is holding the tiller, steering the ship across the sea, which is only just visible as white waves in the bottom right of this detail: it is barely more visible in the light as a whole. The precise, naturalistic lines of the tiller-man’s face, and the crisp, taught curls of his hair couldn’t be more 19th century. The same is true of the detailing of the ship itself. Indeed, this panel is the major area of ‘restoration’ – for which read, ‘reinvention’. Apart from the canopy above this scene, the whole light had been lost by the middle of the 19th century, whereas the glass in the rest of the window is original, according to a contemporary (i.e. Victorian) report. It is not entirely clear how accurate that was, though… The two men in blue at the brow of the ship – just next to the anchor – are praying ardently for God to protect them, and to bless their journey across the sea to foreign lands. Their hats are typical of those worn by pilgrims, even if there are no pilgrim badges attached. The hats, if not their gestures, tell us that they are two of the Palmers. This is not, strictly speaking, part of the story of St Edward, although it will become so. It gives us a hint that the Palmers were using the story for their own ends.

The story really starts in the second light, for which I’m afraid I don’t have a terribly good detail. I hope you can pick out, in the foreground, two men with long white beards – two old men. The one on the right is higher up and wears a blue cloak over a red robe. He has a broad white collar, or cape, flecked with black: ermine, a sign of royalty. But then he also has a sizable gold crown – he is a king. Indeed, he is King Edward. Saint Edward, even. The man on the left wears what appears to be a pale, possibly white cloak over a blue robe. His diminutive stature suggests that he might be kneeling, and his hands are reaching out towards the king, a gesture which the king himself reciprocates. One day when travelling, the Life of Saint Edward the Confessor tells us, King Edward met a poor beggar, who asked him for alms. The king responded, good and holy man that he was, with the gift of a precious ring. The importance of this ring is demonstrated in the third light: we can see it very clearly at the top, just above the trees. The beggar, now clad entirely in blue, but recognisable thanks to the same white, forked beard, hands the ring to one of the two Palmers.

When seen in close-up it becomes obvious how large this ring is – an enormous gold loop mounted with a precious stone which could even serve as a bracelet for the impossibly slim 15th century wrists of these figures. It is certainly far too large for their elegantly stylised fingers. Here the glass is original – apparently – but I’m fairly sure that the painted details of the trees are 19th century. It is exactly the sort of patterning you can find in Morris & Co. windows, even if the firm responsible here was Hardman’s of Birmingham. As it turns out (and doesn’t it always) the poor beggar wasn’t a poor beggar after all, but St John the Evangelist in disguise. Edward the Confessor was known to have had a particular devotion to the Evangelist, so it isn’t entirely surprising. St John revealed himself to some pilgrims in Jerusalem, telling them not only who he was, but giving them Edward’s ring, and asking them to return it to him. St John also asked them to tell Edward that they would soon be meeting each other – in Heaven – in a few months’ time. It was 1065.

In the fourth light (and apologies for the quality of this detail), the Palmers kneel before the king, who sits enthroned, holding the ring in his right hand. It is a similar size, but not as clear due to the condition of the glass and the quality of the detail. Courtiers in red gather around the king, standing and sitting, while the Palmers kneel. Together with the ring, the Palmers passed on St John’s message about the king’s imminent demise, and the rest is history – and the only date that the English are supposed to remember. The story of the ring was first written down around 1161, just under a century after the king’s death, in a Life of St Edward. It almost certainly derives from the fact that, when the tomb of the king was opened (for the first time) in 1102, there was indeed a ring on one of his fingers. This was later taken off when the body was moved (for the first time) in 1163. It became the symbol by which he was most commonly identified – his most important attribute. However, devotion to the saint had waned by the 15th century, when the window was made, as the immigrant St George had long before taken his job as the main patron of England. Edward’s relevance for the Palmers’ Guild was secure, though. The supposition, in the window, that the pilgrims who met St John in the Holy Land were members of the Palmers’ Guild is pure invention. However, the story that the window tells is about them, with St Edward the Confessor being relegated to the role of a supporting actor in their legend.

Christian Liddy has pointed out that in the 1st and 4th lights in the bottom tier the canopies precisely match those directly above them, whereas in the 2nd and 3rd lights they are reversed. It could easily be that, when the windows were replaced into the right tracery in the 19th century, the two central sections were inadvertently installed the wrong way round.

The lower four lights show the continuation of the Palmers’ version of the story: none of this occurs in any version of the Golden Legend. The scenes as now ordered alternate between external and internal locations, with grass and rocks in the first and third, and intricate tiling in the second and fourth – but we should remember that the 2nd and 3rd lights should be reversed, so the two external scenes would be followed by two interiors.

The first light show a procession of clerics led by one holding a processional cross, followed by others with candles, a bible and, I suspect, a thurible (an incense bearer), with the two Palmers further back. They are winding through the countryside towards a building, and might appear to be progressing towards the second light, in which king Edward sits enthroned. However, they should be processing towards the greeting in the third light, from which the right hand detail above is taken. This procession welcomes the Palmers back from the Holy Land, and when they arrive at the gates of Ludlow they are greeted by the chief magistrate, who we can see wearing red, on the left of the right hand detail, where he is embracing one of the Palmers (the other stands in the shadows on the right). Let us overlook the fact that this is supposedly 1065, and Ludlow didn’t exist then, and also the fact that it didn’t have impressive town gates like the one shown in the window until the 13th century. What is important is that the Palmers are being celebrated by the leading citizens of the town. Stylistically, to my eye, the two embracing figures have the most medieval-looking painted detail – slightly scratchy, as if worn with age, and in any case more spare. The same is not necessarily true of at least two of the figures in the background, whose eyes look just a little too naturalistic.

This detail, from what is now the second light at the bottom, shows the two Palmers kneeling before King Edward, their pilgrims’ hats tipped back off their heads as a sign of respect. We can see the intricate details of the king’s crown and ermine collar, which makes me think that even if the glass here is original, the painting of the details must be restoration: it is too specific, too precise, too clear – and too much like other Victorian neo-gothic windows – to be original. His left hand (with admittedly medieval-looking fingers) rests on a piece of paper, decorated with an intricate circular design, which is being taken by one of the two Palmers. Behind them a cardinal, dressed in red, with a broad-brimmed red hat, gestures towards the paper and its design. This represents the Founding Charter of the Palmers’ Guild, given to them, according to this window, by none other than St Edward the Confessor himself. However, as I’ve already said, this is impossible: his death resulted in the Battle of Hastings, which we all know happened in 1066. According to surviving records of the Palmers’ Guild from 1389, the guild itself had been founded in 1284. Historically speaking, though, it might actually have begun earlier, in 1248, when pilgrims – or rather crusaders – returned from the crusade of the French king, Louis IX (Saint Louis of France, in case you were wondering, or if you know your Caravaggio).

In the final light the Palmers, in their formal livery of long blue robes, but without their pilgrims’ hats – they have been replaced by fashionable, 15th century red chaperons – are celebrating with a guild feast. They join hands to express their ‘brotherhood’, and are entertained by a musician playing the harp: friendship and harmony are the order of the day. At the bottom of the light are the words ‘fenestram fieri fecerunt’. This inscription follows a blank space, and if you look back there are similar gaps at the bottom of the other lights, suggesting that this is only the end of a text. Comparison with equivalent inscriptions elsewhere suggests that, in full, it would have read something like, ‘Pray for the souls of the brothers and sisters of the Palmers’ Guild. Here they have had the window made’ – although the only words which survive are ‘have had the window made’. There is no little irony in the fact that none of the ‘sisters’ of the guild (and they are known to have existed) are represented in the window. Apart from this, the imagery is notable for the way in which the guild glorifies itself. In the upper tier it inserts itself into the story of St Edward the Confessor – or rather, it inserts the story of St Edward and the miracle of the ring into the guild’s own story. The miraculous events are framed by the idea that two of the Palmers travelled to the holy land, and returned to Ludlow: these scenes occur in the two left hand lights, one above the other. The two windows at the top right imply that it was these two Ludlow Palmers who were the pilgrims mentioned in the Life of St Edward – which is, of course, pure invention. The central two lights in the bottom tier then demonstrate how central the Palmer’s Guild was to the life and prosperity of the town itself, and also that their authority came from none other than royalty. They were lauded by both the leader of the town and the ruler of the country, and all this because they were trusted by saints. No wonder they felt the right to celebrate in the final window. All this is very useful as far as Monday‘s talk is concerned, as we will now be able to identify at least one of the saints Behind the King in the Wilton Diptych.