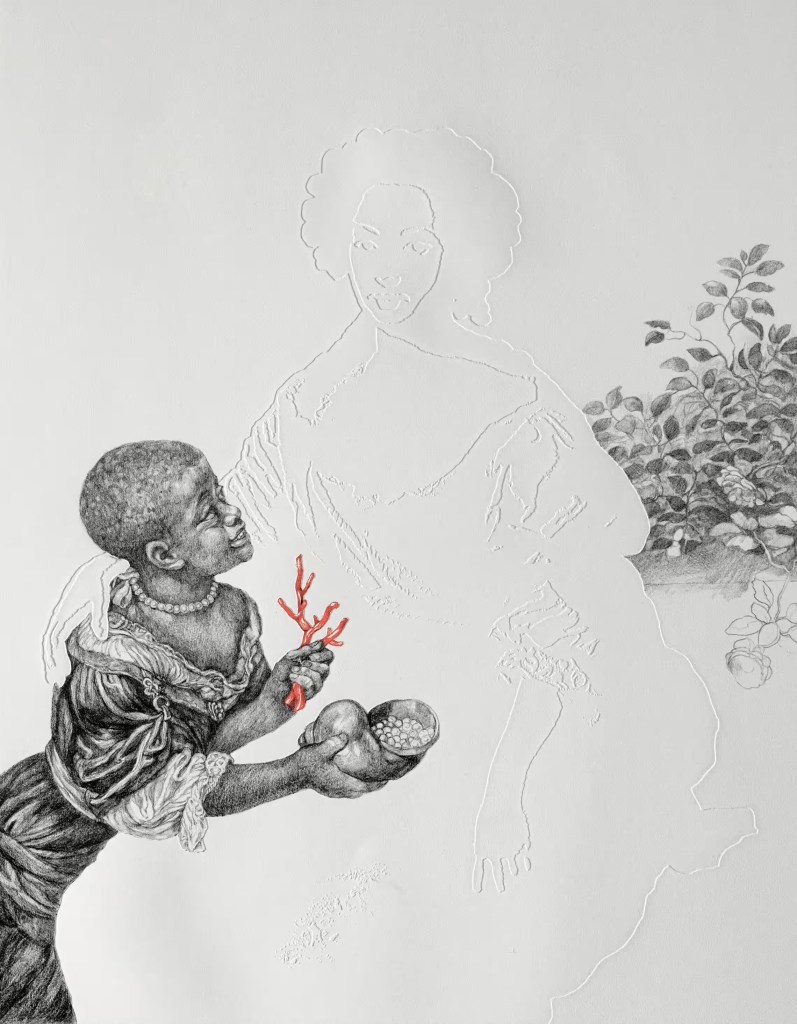

Masaccio, The Adoration of the Magi, 1426. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Happy New Year! And as Monday will be the Feast of the Epiphany, I thought that it would be a good idea to talk about a painting of The Adoration of the Magi today. I have chosen Masaccio’s version rather than any of the many other alternatives because it originally sat underneath the National Gallery’s Pisa Madonna, which will play an important role in the talk on Monday, 6 January at 6pm (which is Epiphany) The Virgin and Child (a brief history). Starting from the earliest examples, I will go as far as Parmigianino: The Vision of Saint Jerome, which will be the subject of my talk on the following week, Monday 13 January. As Parmigianino was one of the leading Mannerist painters, I will attempt to answer the question What is Mannerism? a week later (20 January), and, given that The Vision of Saint Jerome was commissioned by Maria Buffalini, on 27 January I will discuss Women as Patrons in the Renaissance. I have yet to decide what will happen in February, but in March I will be off on The Piero della Francesca Trail with Artemisia – there are details of that and other trips I will make this year towards the bottom of the diary page on my website.

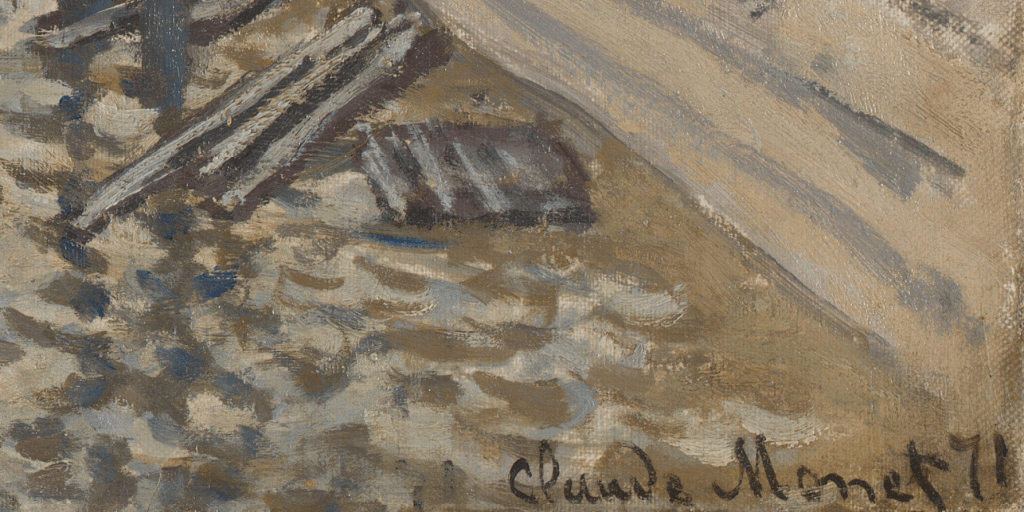

Even without knowing the dimensions of this painting (21 x 61cm, just so you know), its slim proportions might suggest to you that it once formed part of a predella panel (the row of paintings which decorated the box supporting the main panel of an Italian altarpiece), and you would be right. This is the central section from the predella of the polyptych which Masaccio painted in 1426 for Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa – better known today as ‘The Pisa Altarpiece’. It shows The Adoration of the Magi, the episode in the Christmas story when the three wise men, having followed a star from the East, pay homage to the boy born to be king, and present him with their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. The stable is at the left, home to the ox and the ass, and at the right are the horses belonging to the Magi and their entourage. The human drama is therefore framed by animals. Those on the left can be given a sacred interpretation, while those on the right are profane. The Magi are central and are accompanied by their servants, as well as two men in black whose sober dress makes them stand out from the other characters. This all takes place in a stark landscape, with the broad, rounded forms of the Tuscan hills in the background: as so often, the location in which the work was painted is shown to be a place worthy of God’s presence. The light comes from the left, and casts long shadows across the ground – as if the sun has just risen on a new era for humanity.

The light does not come specifically from Jesus, though – he and Mary appear to be shaded by the stable. Nevertheless, Masaccio uses artistic licence to allow him to paint the light falling across the ox’s back, delineating its spinal column and defining the ribs on its right flank – he was the very first to paint a single, coherent light source, even if he does bend the rules from time to time. Outside the stable two forms of seat are contrasted: the saddle of the donkey, and the gold faldstool. As well as reminding us of the journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem, the former also symbolises Christ’s humble birth, while the latter – as the type of throne used by medieval kings in their peripatetic courts – takes us back to the kings’ epiphany, the revelation that this is the boy born to be king. The gold leaf links the faldstool to the haloes of the Holy Family, and to the eldest Magus’s crown, taken off and placed on the ground – as if under Mary’s foot – as a sign of his humility in the presence of God and King (and Queen) of Heaven. It also echoes the gift of gold – usually interpreted as a symbol of Christ’s royalty – which has been given to Jesus by the Magus and is now held by Joseph. There is also a gold star on Mary’s shoulder. This evokes the medieval canticle Ave Maris Stella – ‘Hail, Star of the sea’ – which compares Mary to the North star, our guiding light. The word maris, which means ‘of the sea’, is also a play on the Virgin’s name, Maria.

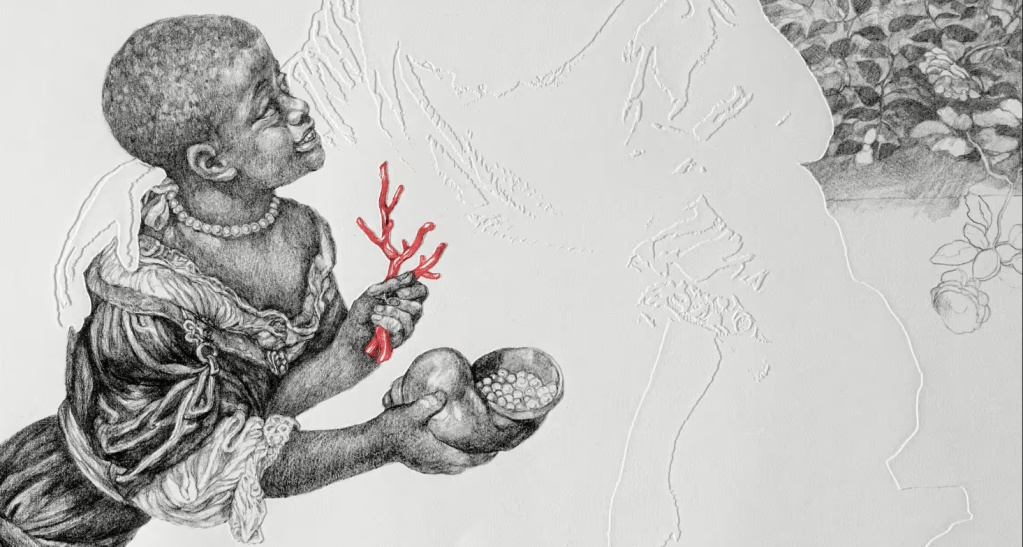

With the eldest Magus kneeling at Christ’s feet, the next two follow, approaching from the right – all three hold their hands as if in prayer. As the second is further back in the space, he catches the morning light fully as it falls behind the stable. His crown has been removed, and is held by the servant behind him, who is wearing a scarlet jerkin. The third and youngest magus is still standing, although his crown is being removed by a servant in black in preparation for his obeisance. Further back another servant, in scarlet like the middle king’s page, holds a second gift. The third is not visible. There are also the two men dressed very soberly in black cloaks and black hats. The older, on our left, wears black hose, the younger wears scarlet – the same as the youngest magus. Already, by the 1420s it seems, red tights were the must-have fashion item for the well-to-do man. The contemporary appearance of these two – contemporary to the 1420s, that is – suggests that they are the patrons of the altarpiece. The older man is Giuliano di Colino degli Scarsi da San Giusto, a wealthy notary from Pisa, and the younger is Marco, his nephew (well, first cousin once removed), who was also a notary. By placing themselves here, they not only suggest that their devotion is such that they too would have travelled far to see the infant Christ, but they also make their presence felt as patrons of the altarpiece: they are both wealthy and devout. However, given that they are in the predella, rather than the main panel of the altarpiece, their choice also suggests a certain degree of humility, as does their position on a level with the servants, rather than next to the Magi themselves.

Having said that, it is possible that they too, like the Magi, have arrived on horseback. There are a least five horses visible: three white, one brown and one black, and they are tended to by three, or possibly four grooms – as far as we can see here. The implication is that the servants would have been walking – but this was standard practice. In Benozzo Gozzoli’s Procession of the Magi in the chapel of the Medici Palace in Florence, the three Magi ride on horseback, as do the ‘important’ members of the entourage (including the Medici themselves), while servants, courtiers and younger members of the ruling family are on foot. It would appear, therefore, that the two donors have travelled with the Magi, and, like them, have dismounted to pay homage to the Baby Jesus. Not so humble after all, even if they are holding back. But it is just the Christ Child they are here to revere? A comparison of this panel with the image which would originally have been directly above it is informative.

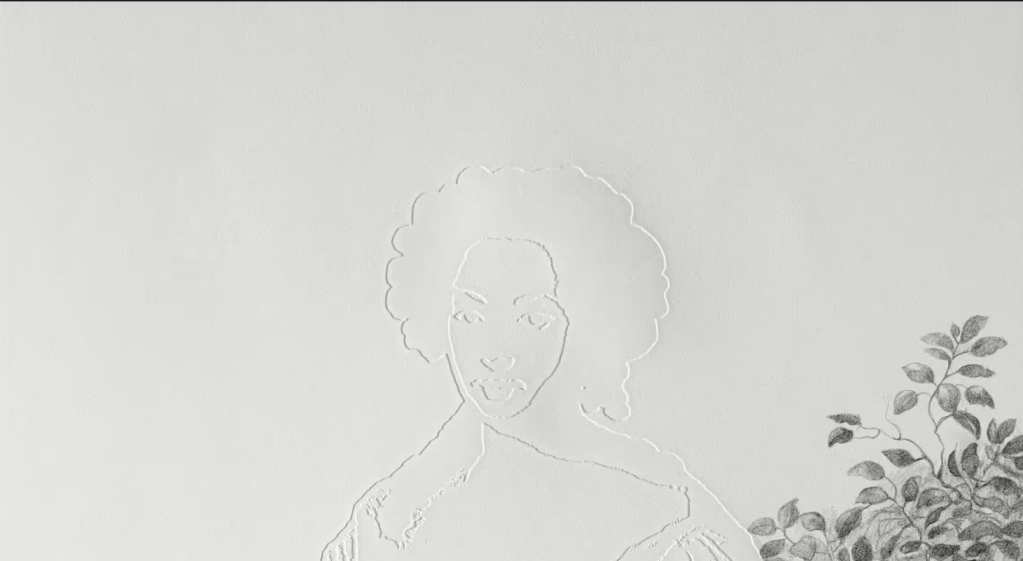

Notice the position of the Virgin and Child in the two images. In both, Mary is enthroned – on the left, on a gold faldstool, on the right on a stone throne. Her back is bent as she curves forward over her child, who sits on her lap with his right foot lowered and the left higher up, as his left knee is more bent. This allows the eldest Magus to kiss his right foot. There is no Magus in the image on the right. However, it just happens to be the first surviving panel painting to use a coherent single vanishing point perspective. The vanishing point is theoretically our eye-level – our most logical focus of interest – and in this painting it is located in exactly the same position as Christ’s right foot. Our eyes are therefore imagined as being on a level with the child’s foot – just like the Magus. The predella panel tells us how to behave: remove your headgear, kneel down and kiss this foot. You are in the presence of God made Man – and, by arranging the perspective this way, Masaccio makes sure that we are suitably humble in our approach.

If we look back to see all three Magi together, it becomes clear that the instructions on how to behave are complete – we just have to follow them. The youngest Magus approaches with dignity, but in all humility, hands joined in prayer, while his crown is removed. The middle-aged Magus is kneeling, bareheaded, and is still praying. The eldest, also kneeling, also praying, has bent lower to kiss the Christ Child’s foot. Curiously, nature does the same. Above the head of the third Magus a light, distant mountain almost reaches the top of the painting. To our left of that, there is a lower, darker hill, whose fissures echo the sleeves of the second king – hill and Magus kneel together. And above the eldest is a space, a gap, which emphasizes the distance between the worldly supplicants and the Holy Family. The view the eldest Magus has of mother and child is directly equivalent to the way in which we see these two in the main panel of the altarpiece. The behaviour of the Magi models ours, effectively an animation of what we should do in front of an image of the Virgin and Child. Having realised this, it is always worthwhile asking yourself, when looking at any depiction of The Adoration of the Magi, whether they are approaching the Madonna and Child themselves, or are they praying in front of an image? Let’s see how many similar examples we can find on Monday!