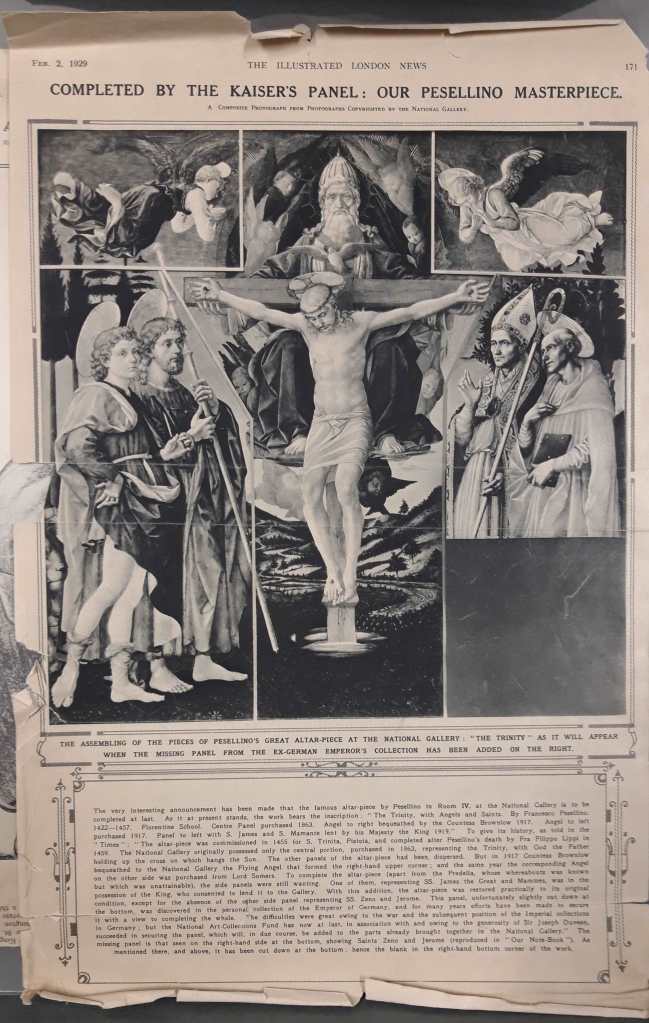

Tilman Riemenschneider, The Last Supper, 1499-1505, St. Jacobskirche, Rothenburg ob der Tauber

I’m so sorry, I won’t be able to talk about Flaming June on Monday, 1 April – you can blame a combination of TalkTalk and Openreach. We’ve finally made it to Merseyside, and should have been connected to the internet on Monday, but instead they sent an engineer on Tuesday. The WiFi worked for two hours, but hasn’t done since. The online ‘bots’ are always useless, and the online chatlines drawn out – and useless. So far they have done nothing to help. There is no guarantee it will be up and running by Monday. I would head to London, but there are engineering works on the line to London so the journey would take twice as long, and, as an extra insult, cost four times as a much. Still, it’ll be Easter Monday, so maybe a break would be a good idea.

The following week I will be in London. My talk Ravenna Revealed, on 8 April at 6pm, will look at the Italian city’s glorious mosaics, some of the best Byzantine art that has come down to us. For me this will be preparation for a visit to the town itself with Artemisia, the ‘adult’ branch of Art History Abroad. That trip has been full for a long time, but there are still a few places available if you fancy joining me in Delft in May – especially if you’re a fan of Vermeer or missed the big exhibition last year. It’s a beautiful, small town, far more truly Dutch than Amsterdam, with picturesque views, fine churches, a great museum and impressive restaurants. We will have a day trip to The Hague to visit the Mauritshuis (with three Vermeers – including The Girl with the Pearl Earring and the View of Delft – not to mention Fabritius’ The Goldfinch), and on the way back to the airport we will stop off at the Rijksmuseum to see their four Vermeers (including The Milkmaid), among other treasures. So that’s a fifth of Vermeer’s surviving works! Full details are given on the blue link above, or here: it would be lovely to see you (please mention my name if you do book – thank you).

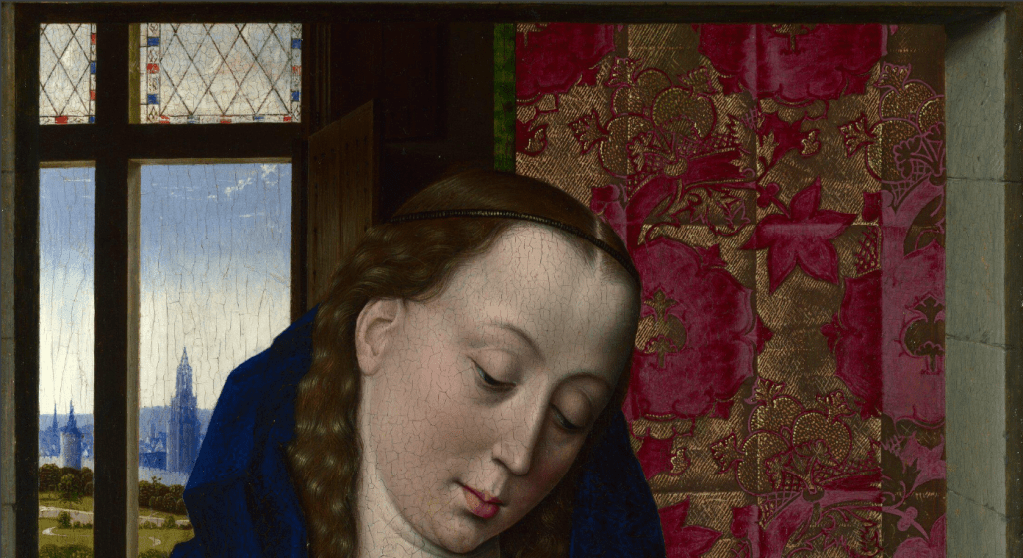

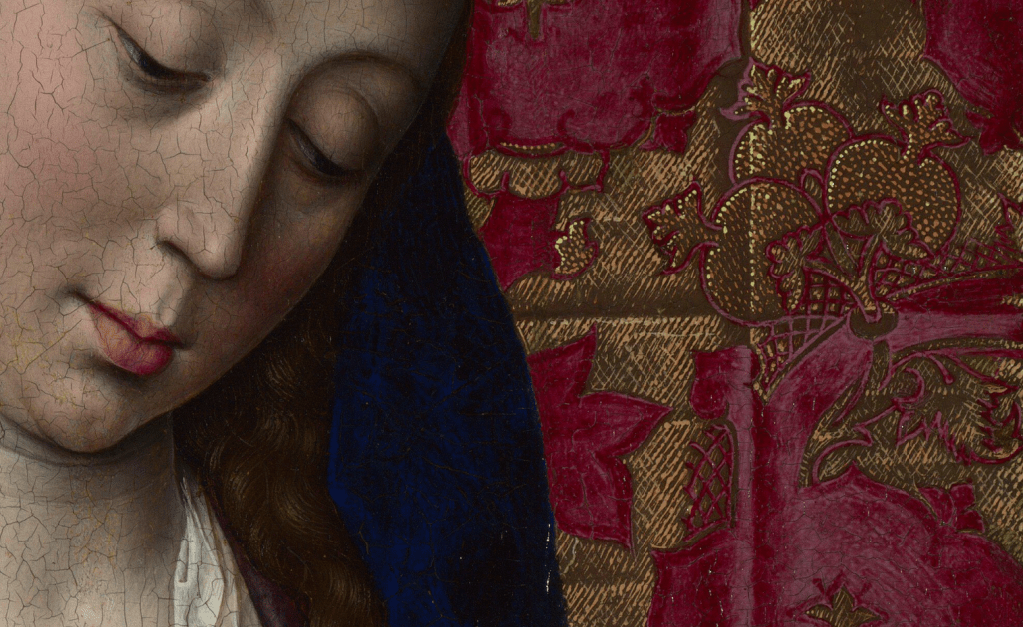

There are also still a few spaces left for the next In Person Tours of the National Gallery on 9 and 11 April, looking at Jan van Eyck and the northern renaissance, the second generation of Florentine renaissance artists, and the fifteenth century in Siena – for links to those, giving full details, it would be best to check the diary. I have rescheduled Frederic Leighton and Flaming June to Monday 22 April, just after I have returned from Delft (if you have booked for that already, you should have had a least one email detailing the change of date, and offering alternatives should you not be available). I will follow that up on Monday 29 April with an introduction to the National Gallery’s upcoming exhibition, The Last Caravaggio, which is due to open on 18 April. For now, though, as it’s Maundy Thursday (Maundy: from the Latin mandatum, ‘command’, referring to the instruction that Christ gave to his Apostles to love one another), I thought it would be good to think about The Last Supper. This turns out to be the very first post I wrote specifically for this website, as you’ll see below. The first three weeks of the blog were posted on my Facebook Page, and started just before lockdown. It was only at the beginning of the fourth week that I managed to find this, a better forum. I have edited the text as little as possible to hold onto the very specific feeling of that peculiar time.

Day 22 – Tilman Riemenschneider, The Last Supper, 1499-1505, St. Jacobskirche, Rothenburg ob der Tauber.

It is the beginning of Week 4 of #pictureoftheday and I bring you a whole new innovation: I finally have my own website, and if you want to, you can head to the ‘home’ page and subscribe to my blog:

Alternatively, of course, you can just keep reading it here. But if you know anyone who might like it, who is not on social media, please do tell them!

On with today’s picture! We are continuing, really, from #POTD 18, where I talked about Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, a relief carving on the left wing of Tilman Riemenschneider’s Holy Blood Altar. The Last Supper here is another detail from this remarkable structure, which is enormous, and quite hard to understand from a photograph. Nevertheless, you can see one view of the whole thing here:

As with most carved altarpieces like this the most important part is the central section, with carved wooden sculptures encased in what is effectively a box. This section is called the ‘corpus’, as it is the main ‘body’ of the altar. This can be shut away with the two wings, which are hinged like doors. The wings were never decorated as richly as the corpus – sometimes they were just painted, a far cheaper form of decoration than carving, whatever the relative values are now, and sometimes, as here, they were carved, but in low relief. The wings would be kept closed to protect the corpus from dust, and opened during the Mass, or on special feast days. In particular, they would usually be kept closed during lent, a period of calm, quiet contemplation, where any notion of celebration or of excess is supposedly put away. However, as the corpus of the Holy Blood Altar illustrates The Last Supper, which takes place towards the end of Lent, it might not make sense to close it off. In addition to this, the physical structure of the piece – the carpentry as much as the sculpture – implies that it might not have been possible to close it anyway.

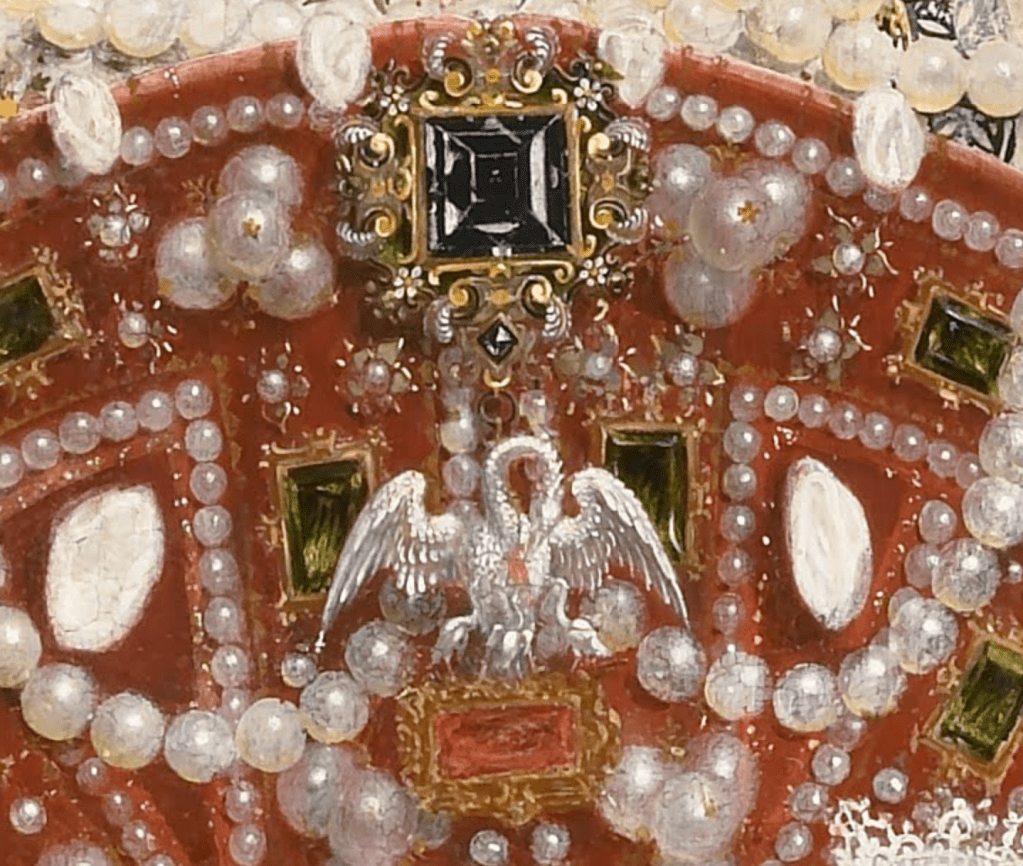

The corpus is raised above the altar by what is often called a ‘predella’. In a painted altarpiece this would be a strip of pictures on the box which supports the main panel, but in this case it is more of an open framework designed to house a small crucifix, and two adoring angels. It was at the Crucifixion that Christ’s blood was shed. This is, of course, of huge importance given the name of the altar. The church of St James boasted a relic of the Holy Blood, and the altar was designed as an enormous reliquary. Above the corpus, effectively standing on the roof of the Upper Room where the Last Supper is taking place, there are two kneeling angels holding another cross. There is no figure of Jesus here, but there doesn’t need to be, as it is this cross which contains the precious relic: Jesus (or at least, his blood) is actually there. On either side we see the Annunciation. The Angel Gabriel, standing on the right, announces to the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of God. But he announces the coming of the Messiah across the relic of the Holy Blood – so with the news of Jesus’ birth comes the inevitability of his future death. At the very summit of the filigree work decorating the superstructure is one last sculpture – Jesus himself, as the Man of Sorrows. He is dressed in a loincloth and wears the Crown of Thorns. He points to the wound in his chest from which the blood flowed. As he is directly above the relic, it is as if the blood flows down into the reliquary cross – and on, downwards, into the chalice at the Last Supper. Or it would, if we could see a chalice.

That is the point of this sculpture: it was at the Last Supper that Christ instituted the Eucharist. According to Mathew (26:26-28):

‘And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed it, and brake it, and gave it to the disciples, and said, Take, eat; this is my body. And he took the cup, and gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, Drink ye all of it; For this is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins’.

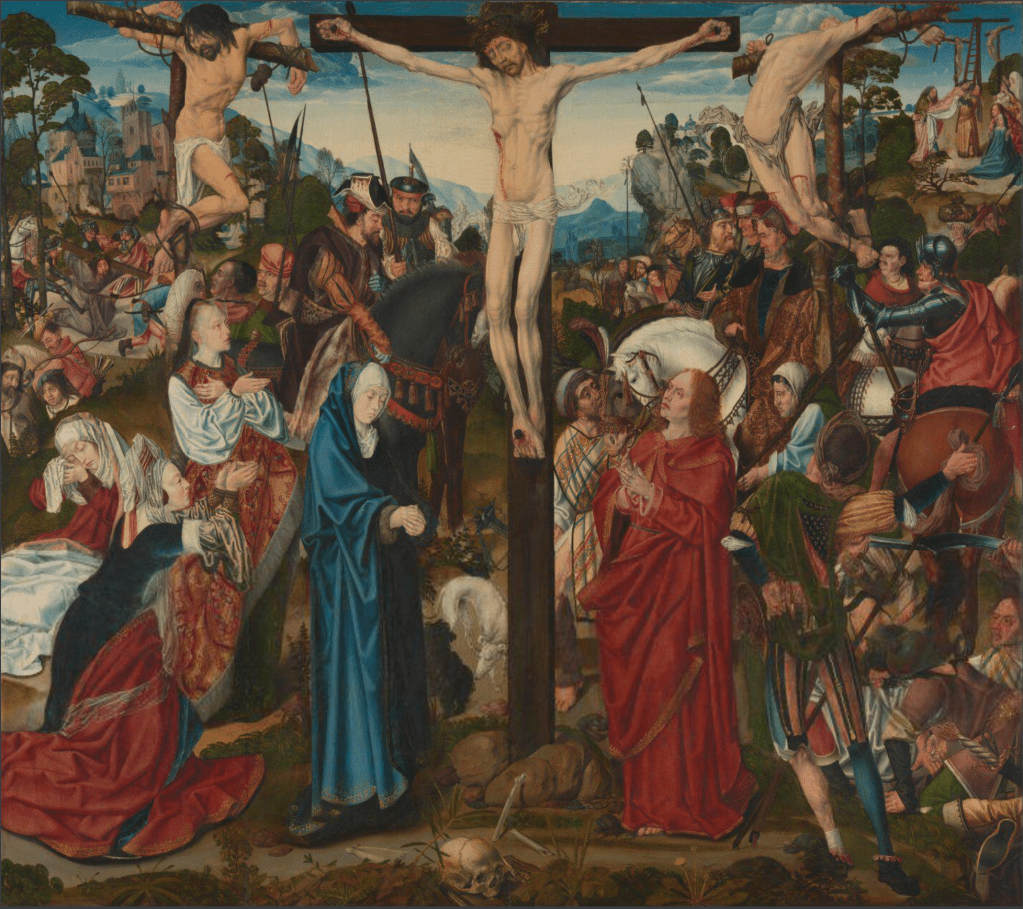

Before the 10th plague of Egypt (see #POTD 21, yesterday), the houses of the Israelites were marked with the blood of a spring lamb, which was sacrificed and then eaten. The blood on the door told the avenging angel not to kill the firstborn of that household – the Jews would be saved. Jesus takes this symbolism for himself, and becomes, as John the Baptist announced, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world. In the Eucharist, the bread and wine become his body and blood. In Christian belief, Jesus becomes the Passover lamb, and his blood means that Christians will be saved.

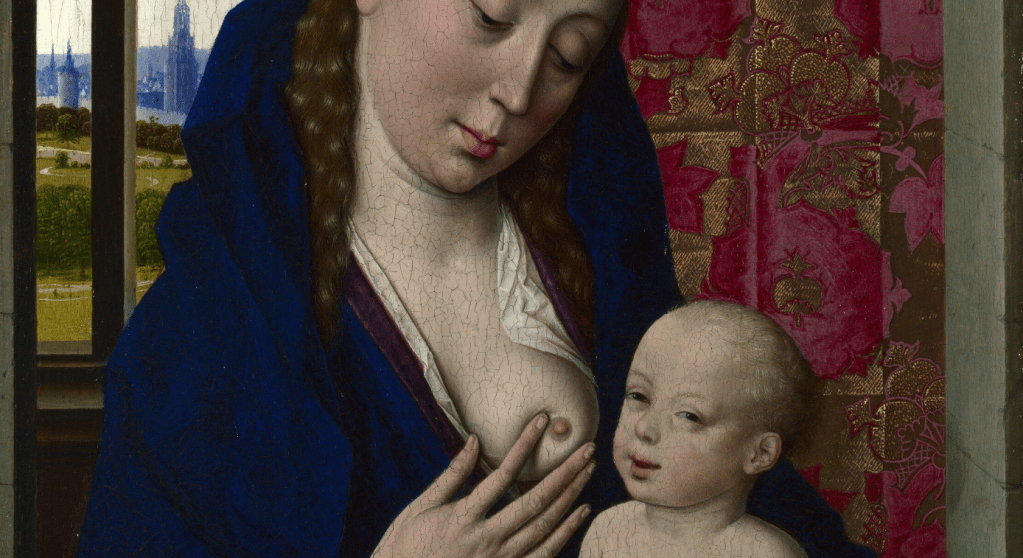

Nevertheless, we are witnessing a slightly different point in the drama, just before the institution of the Eucharist. Jesus has announced that one of the number would betray him – and some of them are still discussing which one it will be. The man on the far right appears to be accusing his neighbour, who points to himself as if to say, ‘No, not me guv’nor’. The three above them are looking confused – and maybe a little guilty. The implication is that, whenever anyone does anything wrong, they are effectively betraying Jesus. However, they seem to be unaware that we have already reached the denouement. Judas has stood up and is ready to leave, clutching a moneybag containing the thirty pieces of silver – the blood money – in his left hand. He gets a fantastically central position – but not, apparently, a chair. Maybe he has kicked it away, and it has fallen out of the frame.

Actually, it’s better than that. The whole sculpture is carved out of several different blocks of wood, all fitted together – and Judas is carved out of a block on his own. Look at the structure of the woodwork making up the floor of the room: can you see that his feet rest on a separate plank? Well, the whole figure can be removed, and tonight, in St Jacobskirche, maybe it will be. Judas will leave the building. This would then allow a better view of the youngest of the Apostles, John the Evangelist, asleep on Jesus’s lap. And a clearer view of Christ’s right hand, withdrawn, almost limp, as even he appears to be wary of blessing Judas.

This really is the perfect piece of drama. Looking again at the overall structure of the altarpiece, we see the Entry into Jerusalem in the left wing (#POTD 18), and, as I suggested then, the fact that you can only see the shoe on the donkey’s foot from the left-hand side implies we should be with the Apostles, following Jesus, through the gate and into the city. This takes us into the Upper Room, depicted in the corpus, where we see Jesus and the Apostles at the Last Supper. From here, Judas heads off to the high priests – and to the arresting soldiers – while Jesus goes to the garden of Gethsemane, depicted in the right-hand wing of the altarpiece. The drama continues from left to right, taking us ever closer to the point where blood – the Holy Blood – is actually shed.

Even within the Last Supper, the drama is palpable throughout the day. On Sunday I showed a picture of the windows of the Upper Room seen from behind the altarpiece – they let light in from the windows of the church itself. The biblical characters are illuminated with the same light as we are, they are in the same world as us, and we become part of their narrative. I had wanted to see this, Riemenschneider’s masterpiece, for thirty years, and I finally saw it for the first time last December. I was lucky enough to spend the whole morning with it. It was a beautiful, crisp, winter’s day, with milky sunshine and a blue sky. Sitting in front of the altar, it was at first evenly lit by a diffuse light. As the Earth revolved the sunlight fell first onto Christ’s hand – the one that had shared food with Judas, the one that appears unable to bless the departing traitor – and then, it fell onto Judas himself. He appears almost blinded by the light… and makes to leave.